Consider this scenario, unfolding in a country that views itself as the world’s leading democracy:

- A cynical but charismatic demagogue emerges as a disruptive force in politics — a person of wealth, privilege and fame who claims to represent a mass movement of ordinary people, but uses it for his own purposes.

- He leads a right-wing, ethnic nationalist paramilitary force with more than 100,000 members, which proclaims itself more loyal to the true spirit of the nation than the actual elected government, and threatens armed rebellion.

- The leader of the mainstream conservative opposition party pledges full support for the paramilitary movement’s campaign of resistance, up to and including civil war.

- Conspiracy theories rooted in a long history of ethnic and religious bigotry spread widely in support of the potential rebellion, including claims about the savage, superstitious and bloodthirsty behavior of previously disempowered groups now out for revenge.

- A leading government official is told to cancel all public appearances because the risk of violent assault or assassination is too high.

- Dozens of high-ranking military officers, in collusion with senior commanders and right-wing political leaders, stage an open mutiny, pledging to resign or be dismissed rather than obey the lawful orders of the elected government.

That might sound like the funhouse-mirror narrative for a dystopian Hulu series, an alternate history patched together from things that actually happened, things that almost happened and things that didn’t quite happen over the last decade or so in Trumpian America. But it’s actually more like an object lesson, or a warning to those who insist that whatever else may go wrong, a stable and established liberal democracy cannot collapse into chaos, dictatorship or civil war.

Because everything on that list really did happen, just over 110 years ago in the United Kingdom, which despite its peculiar political history and lack of a written constitution was abundantly confident in its democratic credentials — and, not to drive the point home too hard, was given to lecturing other countries about the superior wisdom, tolerance and flexibility of its system.

One reason why you probably haven’t heard about the hair-raising British political crisis of 1911 to 1914 — indeed, why hardly anyone has heard about it — is because the catastrophe was averted, but not by everyone coming to their senses and hashing things out in a jolly spirited debate over snifters of brandy and linking arms for a chorus of “God Save the King.” No, the crisis ended because the First World War broke out in the summer of 1914, and the next four years of pointless carnage led to something like a million dead British soldiers (and roughly 20 million deaths overall), redrew the maps of Europe, Africa and the Middle East, and marked the beginning of the end for Britain as an imperial superpower.

After all that, no one especially wanted to revisit the details of a domestic political crisis that seemed insultingly tiny in comparison — or to admit how close it had come to tearing the Land of Hope and Glory apart. Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith, who had blundered his way into the Home Rule Crisis (as it is known to historians) through a great deal of erudite dithering, wrote to his mistress on the day war was declared that this solution was like “cutting off one’s head to get rid of a headache.” Another prominent member of his Cabinet, he added, was “all for this way of escape from Irish troubles” — a young man named Winston Churchill.

Yes, the Home Rule Crisis, which according to eminent Oxford historian Robert Blake strained Britain’s incrementally constructed democratic institutions “to the uttermost limit,” was the long-tail result of conflict in Ireland, the perennial stone in the British Empire’s shoe. If the specifics are both historically remote and overly familiar — every so often the British had to confront (or, as in this case, avoid) the question of whether to let the unruly inhabitants of the colonized island next door govern themselves, and on what terms — the passion and emotion, as noted above, feel strikingly contemporary.

Viewed from the overheated ideological landscape of America in 2024, Britain’s “Irish troubles” may look like an irrelevant, if faintly romantic, relic of the past: indistinguishable tribes of white people fighting over a rain-soaked island on the Atlantic fringe of Europe. On the other hand, and at risk of special pleading or narcissism (my last name is specific to the eastern half of County Clare), I would argue that the strange story of Ireland over the past couple of centuries — precisely because of its claustrophobic scale and intimacy, its whiteness, its universe of invented mythology — offers lessons, or at least asks questions, that have much broader resonance. The Home Rule Crisis is just one example.

While the longer backstory of the events that brought Britain “to the brink of civil war” in 1914 (to quote Irish historian Ronan Fanning) has filled many scholarly volumes and inspired many histrionic ballads, here’s the tl;dr on the Home Rule Crisis: It was a double dose of historical irony. Two different British solutions to the long-running Irish problem backfired simultaneously, leading to the political equivalent of an uncontrolled chain reaction.

One of those was the Act of Union in 1801, which sought to short-circuit the Irish propensity for rebellion by creating a brand new nation-state, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. (Any usage of that term to describe Britain before the 19th century is anachronistic.) To cut a long story short, that didn’t go well: Several more rebellions followed, as did the Great Famine of the 1840s, which reduced Ireland’s population by almost half and permanently soured relations between the two islands.

By the late 1880s the Liberal Party — which, broadly speaking, represented Britain’s reformist middle class — had halfheartedly committed itself to “home rule” for Ireland, which meant … well, nobody was sure what it meant, but some form of self-government well short of actual independence. That wasn’t likely to please all Irish nationalists in the first place, and immediately became a hot issue for the pro-imperialist British right, which depicted home rule as a woke radical socialist surrender to savage Fenian terrorists. (OK, they didn’t say “woke,” but pretty close.)

In the event, they accomplished the latter but not the former: Home rule never happened at all. Most of Ireland ultimately became an independent state in 1922, after several years of bloody guerrilla warfare. By that time, the Liberal Party had been wiped off the political map (as had the moderate Irish nationalists), and would never hold power again.

What went wrong? Damn near everything, including that exciting list of events mentioned above. First and foremost, there were the unintended long-term consequences of Britain’s other, much earlier scheme to exert control of Ireland.

Both the Liberals and the Irish nationalists, for different but equally disastrous political reasons, pretended to ignore the entrenched population of nearly a million Protestants in Ireland’s industrialized northeast, who wanted absolutely no part of home rule. Or, as many of them imagined it, “Rome rule,” a brutal but incompetent dictatorship of drunken, brawling Irish Catholics under the personal direction of the pope. One popular conspiracy theory held that the houses of respectable Protestant families were being raffled off in Catholic churches, to be invaded by unwashed broods of Irish peasants as soon as home rule was established.

Such fantasies were an instructive form of projection, of a sort that may seem oddly familiar today. The Ulster Protestant or Unionist community (also called the Orangemen, for their distant ancestral connection to William of Orange, aka King William III) was one of the earliest historical instances of what is now called settler colonialism — and perhaps the first such group to turn around and bite its creators.

Ulster Protestants were (and are) largely descended from Scottish and English settlers imported during the 17th-century “plantation” of Ulster, which, not coincidentally, was contemporaneous with the first English colonies in Virginia. (Many white people in Appalachia today share exactly this “Scotch-Irish” ancestry.) During the reign of King James I, nearly all agricultural land in Ulster was confiscated from native Irish chieftains and delivered to new owners, required to be English-speaking Protestants loyal to the crown.

While the original plantation scheme envisioned the complete ethnic cleansing of Ulster’s indigenous Irish-speaking Catholics, that proved impractical — the new landlords required laborers and servants, after all. More ambitious Anglo-Irish reformers, including the Elizabethan poet Edmund Spenser, believed that “Irish nationality had to be uprooted by the sword,” in the words of historian Roy Foster, but later generations of British officials were less enthusiastic about overt genocide.

Flash-forward to the 20th century and the lukewarm campaign to enact home rule in Ireland, and we find Ulster Protestants occupying a strange, half-stranded position: an embattled and despised minority within Ireland as a whole, still perceived as alien invaders after 300 years, but a dominant majority in their own corner of it. There was literally no way that would end well.

Ulster Protestants have frequently been compared to the white community in apartheid South Africa, but in their glory days they preferred to see themselves as the righteous but persecuted Hebrews of the Old Testament, a theme elaborated in dozens of fire-breathing sermons. Their most extreme self-image, in fact, was akin to contemporary right-wing Zionism: an enlightened fortress of civilization, surrounded by violent savages who practiced a sinister, cult-like religion (and who were eager to settle old grudges).

If it's unfair on many levels to compare the charismatic Anglo-Irish lawyer Edward Carson — who had previously destroyed Oscar Wilde’s career in a notorious 1895 civil suit, before becoming the demagogic figurehead of the anti-home rule movement — to Donald Trump, it's also irresistible. Like Trump, Carson had no particular attachment to the people he supposedly represented: He was a cosmopolitan Dublin-London gentleman, not a religious zealot or anti-Catholic bigot, and he found the inbred political culture of Protestant Ulster stultifying. In later life he expressed misgivings about his role in the crisis, concluding that he had been manipulated into a compromise he never wanted: the eventual partition of Ireland and the creation of the Protestant-ruled mini-province of Northern Ireland, whose status has remained unsettled ever since.

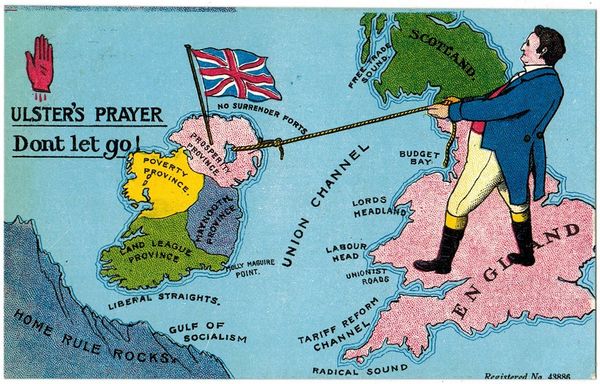

Carson’s original goal was to keep all of Ireland in the Union, and to pursue that he shamelessly manipulated Orange sentiment in a highly effective MAGA-style propaganda campaign, complete with memorable slogans (“Ulster will fight and Ulster will be right”) and hyper-patriotic symbols — one mass rally in 1912 featured a 1,200-square-foot Union Jack, reportedly the largest ever made. He depicted Ulster Protestants as more deeply British than the actual inhabitants of Great Britain, while also practicing open sedition and plotting insurrection. That could either be considered deeply un-British or a throwback to the kingdom’s much earlier days.

Carson’s rhetorical strategy was also strikingly similar to Trump’s: By declaring his radical intentions openly, he put his opponents in the world of normal politics on the defensive, forcing them either to overreact (and potentially appear hysterical) or fail to take the threat seriously and then be taken by surprise.

By September 1911, Carson had laid “the groundwork for civil war,” to quote Ulster historian Alvin Jackson, and was ready to go public in a speech before 50,000 Unionists: “We must be prepared — and time is precious in these things — the morning Home Rule passes, ourselves to become responsible for the Government of the Protestant Province of Ulster.”

The Liberal government and its Irish nationalist partners kept trying to convince themselves that was all hot air — sounds familiar, right? — but the wish-casting got more challenging after Carson unveiled the Ulster Covenant of 1912. That was a pledge, signed by nearly 450,000 Protestants, to use “all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland” and not to recognize such a parliament if it happened. A few months later, he announced the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force, a private army of more than 100,000 men who had signed the covenant.

Along the way, Carson acquired a powerful ally who gleefully poured fuel on the flames: Andrew Bonar Law, a right-wing firebrand with Ulster Presbyterian roots who became Conservative Party leader late in 1911 and pushed the previously staid Tories “to embrace a policy of revolution without parallel in modern British history,” in Ronan Fanning’s words. Bonar Law was both a true believer in the Ulster cause and a shrewd political operator, who correctly perceived that home rule could be used to bring down Asquith and the Liberals.

Machiavellian or not, Bonar Law was the secondary Trump cognate of the home rule crisis (or possibly the Mike Johnson), and without him the crisis could not have escalated so far or so fast. His infamous Blenheim Palace speech of July 1912 bears comparison with the most inflammatory things Trump has ever said, beginning with his denunciation of Asquith’s coalition government — all of whose members had been elected by the voters — as “a Revolutionary Committee which has seized upon despotic power by fraud”:

In our opposition to them we shall not be guided by the considerations or bound by the restraints which would influence us in an ordinary constitutional struggle. … I said the other day in the House of Commons and I repeat here that there are things stronger than parliamentary majorities. …

I can imagine no lengths to which Ulster can go in which I would not be prepared to support them, and in which, in my belief, they would not be supported by the overwhelming majority of the British people.

It seems unlikely that the public would really have supported Carson’s paramilitaries in open combat with British troops. But Bonar Law had tapped into a deep current of upper-class and working-class nationalism, and the exhausted government — bearing very little resemblance to a “Revolutionary Committee” — responded with a series of craven capitulations, while still trying to hammer out the irrelevant details of a home rule bill that would never happen.

When dozens of officers at the Curragh, the British Army’s principal base in Ireland, announced in March 1914 that they would refuse orders to enforce home rule in Ulster — with the private encouragement of generals in London — Asquith’s Cabinet caved in to their demands and covered up the entire affair, insisting that no mutiny had occurred because no direct orders were disobeyed. Three weeks later, the Ulster Volunteers smuggled 25,000 German rifles and 3 million rounds of ammunition into Ireland in a spectacular two-day operation — although “smuggled” is hardly the right word, since newspaper reporters were invited to watch while authorities carefully stayed out of the way.

The stage was set for the kind of violent throwdown more often associated with decaying Balkan duchies or post-colonial dictatorships, at least until the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand intervened. Journalists from around the world converged on Belfast, hoping to see the first match struck. Would Carson form a breakaway Ulster republic? Would Bonar Law lead or authorize a coup against the Asquith government? Would civil war break out throughout Ireland? Militant Irish republicans had been paying close attention to Carson’s tactics — which anticipated Mao Zedong’s maxim about the source of political power — and would eagerly emulate his example in the years ahead.

Instead, war broke out across Europe, and Asquith made his mordant headache joke on the way to the historical dumpster. It was a bitter recognition that mainstream democratic politics, at the heart of an empire that still believed it ruled the waves, had proven completely inadequate in the face of what looked at first like a minor local dispute but unfolded into explosive karmic blowback from decisions made long ago by people long dead. It’s not a new lesson, but it never stops being relevant: History has a tendency to punish great nations for their arrogance.