Listen to an audio version of this story

Angela Monaghan was perched on a lawn chair when she learned that she was dead.

A fifty-six-year-old high school teacher from the township of Tiny, Ontario, Monaghan had gone to her nearby Canadian Tire to apply for a store credit card. As a board member for a local music association, she had been tasked with buying sheet music. Because it’s a small organization, it was easiest for Monaghan to put the card in her name, make the purchase, and pay it off quickly.

But her application was turned down. When she asked why, the sales associate told her she would need to call Canadian Tire Financial Services. So Monaghan took a seat on the nearby patio set and dialled. The financial services rep explained that TransUnion, one of Canada’s two main credit bureaus, had reported her as deceased. Because of this, her credit report had been wiped clean, her score reset to zero. Canadian Tire couldn’t issue a credit card to someone with no credit rating. Given that she was, in fact, alive, Monaghan pressed the issue. The worker on the other end of the line held firm. “They said I needed to take this up with TransUnion,” Monaghan says. “That’s when the nightmare began.”

It was the summer of 2019, and her husband, Dave, had died two years earlier after a long battle with cancer. Somehow, TransUnion had mixed up husband and wife, marking Monaghan as dead. Luckily, she is nothing if not meticulous. She had kept careful records of everything that could establish her existence—purchases, appointments, calls. She set to work fixing the mistake. How hard could it be? she thought.

It took two years for her old credit score to be reestablished. Two years of faxing in detailed documents—including Dave’s death certificate—only for the mistake to reappear. During that period, her life was effectively stalled. She considered moving, as it was painful to stay in the house she had shared with her late husband, but having a credit score stuck at zero meant she couldn’t get a new mortgage. She opted to do some renovations instead, but her nonexistent credit score scared off builders. Luckily, she found a contractor with whom she had a mutual friend, someone who vouched for her character. To make matters worse, Monaghan was recovering from a traumatic head injury at the time; she’s still on leave from her job. She thought about making the two-hour drive from her home to TransUnion’s offices in Burlington, but she wasn’t physically able to.

While her story sounds extreme, it’s far from an aberration. Errors have been a long-standing issue with credit bureaus in North America. One recent survey from Consumer Reports found that more than one-third of credit reports in the United States contained false information. In 2021, the Ontario Consumer Protection Agency received the equivalent of a call nearly every week related to credit report errors. And those statistics don’t represent the total number of errors—just the ones caught and reported. The most common mistakes involve incorrect names, addresses, or phone numbers. Bills that are paid on time can show up as late. Closed accounts can show up as open, or accounts can be duplicated, or credit limits can be wrong. Not only does the complexity of credit scoring formulae make them prone to errors, the automated nature of these scores can make inaccuracies harder to rectify—even after repeated efforts by a consumer.

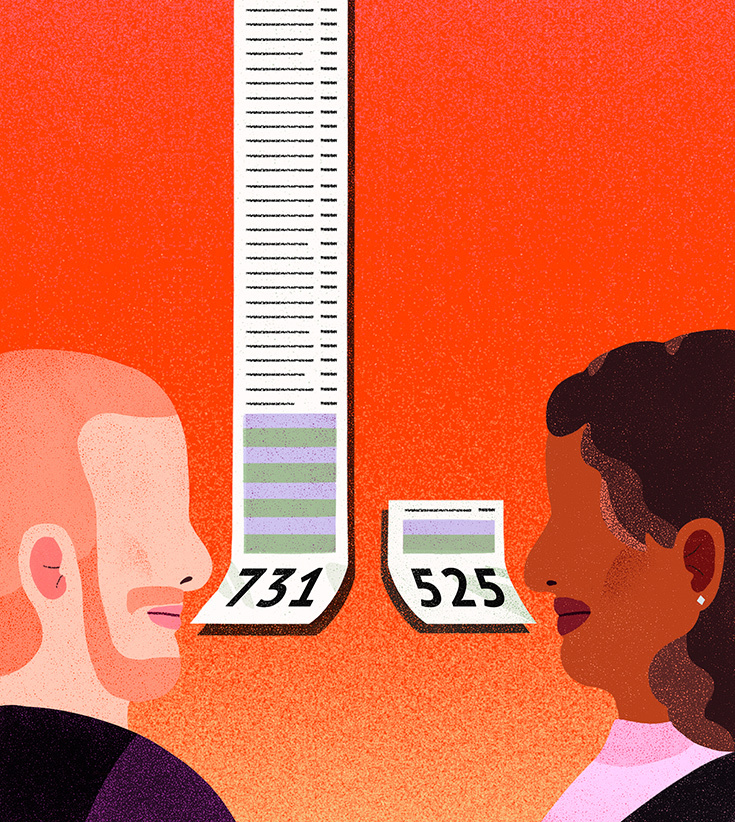

And these mistakes matter—even the most minor can cause havoc. A credit score represents your credit risk, or the likelihood you will pay your bills on time. Canada and the United States use a similar rating system, issuing a three-digit number. In Canada, that number typically ranges between 300 and 900. This score is like your financial first impression. A poor first impression doesn’t just jeopardize your ability to borrow money or make purchases; it can also limit where you can live and what kinds of job you can get: credit checks on prospective tenants and employees are increasingly the norm.

In response, an entire secondary industry has popped up to help people repair their credit scores, offering tips and promises of quickly raising rankings by up to 100 points. Its existence preys upon a visceral feeling consumers have: that our credit scores vouch not just for our finances but for our characters. Are we reliable? Do we keep our promises? They are a mark of how much faith the system has in us.

This anxiety has shot up during the COVID-19 pandemic, when finances have been especially tight. In fall 2021, a survey from credit bureau Equifax showed that Canadians were checking their credit reports at rates far higher than in prior years. That same survey also found that a significant number struggled to understand those reports, especially when it came to spotting mistakes.

That finding highlights a frustrating aspect of credit scores: while they are linked to nearly every facet of our lives, their inner workings are, for many, steeped in mystery. Despite not grasping precisely how credit bureaus operate—and despite knowing that their scoring systems are persistently inaccurate—we’ve allowed them to be the judge and jury of who is working hard enough and who has shown enough determination to deserve a helping hand. And it’s nearly impossible not to participate: you can’t lease a car or buy a house without abiding by the system credit scoring helped create. Credit scores can improve your life. They can also ruin it.

In its earliest form, credit was as simple as the local baker fronting you bread, knowing that payment would come at the end of the week. But, as hamlets and villages became towns and cities, credit became formalized. England is the birthplace of modern credit reporting, with accounts going as far back as 1803, when groups of tailors came together to swap information about which customers would reliably pay their debts. This practice started popping up in different trade groups and unions, growing into regular newsletters and publications that listed everyone who had failed to pay. One such newsletter began in 1826, distributed by the Society of Guardians for the Protection of Tradesmen against Swindlers, Sharpers, and Other Fraudulent Persons. Since that was a bit of a mouthful, the group eventually became the Manchester Guardian Society and began employing a data officer to ensure the accuracy of its information.

New York’s Mercantile Agency formed in 1841, aggregating information on its customers and distributing it to any lender—for a fee, of course. By 1864, it had compiled a ranked list of tens of thousands of companies across the United States and Canada (where it focused mainly on Quebec and Ontario-based businesses). These reports were handwritten and mentioned a business’s debts and profits as well as subjective commentary on the owners, their spouses, and their associates. Credit managers logged and filed notes on customers’ characters and appearances. If there was a marriage, birth, death, promotion, or even a change in spending patterns, it was recorded. The credit managers who fed information back to the Mercantile Agency were encouraged to document things like community standing. Was the person in question active in their church? Did they have any confirmed—or assumed—problems with alcohol?

Racialized and marginalized shoppers were regularly listed at the bottom of the hierarchy. As Josh Lauer writes in Creditworthy: A History of Consumer Surveillance and Financial Identity in America, prejudice was “codified as standard operating procedure.” According to a 1922 guidebook prepared by the Retail Credit Men’s Association of New York City, “Negroes, East Indians,” and “foreigners” were among the worst credit risks, just edging out “men and women of questionable character” and “gamblers.”

This ranking system allowed early credit bureaus to cultivate an air of legitimacy within the business community. Credit bureaus “existed so that businesses could go to them and trust that they were doing background investigation and vetting customers,” Lauer explains. Early credit bureaus would even align themselves with law enforcement agencies, sharing information with local police to help solve crimes. That relationship became stronger in 1937, when the US Department of Justice arranged to purchase credit reports to help its officers build suspect profiles. “It just legitimized their entire operation into something that was civic in its orientation and for the good of the community,” says Lauer.

In the late nineteenth century, as North American cities got bigger, more changes were afoot. In Canada, the Hudson’s Bay Company moved its fur trade away from a barter system to a cash-based exchange. Officials had to therefore keep more-detailed ledgers, complete with credit lent to buyers. The company eventually centralized and invested in a new phenomenon: the department store. To help turn over bigger quantities of merchandise, outlets like Hudson’s Bay wooed shoppers by offering staggered payment plans. Within a few decades, credit accounts at these department stores were common, along with charge cards specific to that store, which would get tallied up monthly or quarterly. The credit account was shorthand for the credit manager knowing you. It signified that you or your family had a relationship with the store and could be relied on to pay an outstanding amount in full. The store’s decision to trust people came first (usually through a credit manager who reviewed each application), followed by the charge account—and, much later, by the credit score itself—as a way of simplifying that process.

Modern credit bureaus have their roots in this early system. Equifax, currently one of the two main credit bureaus in Canada, was established in 1899 as the Retail Credit Company. It moved to Canada in the early 1900s and expanded widely. TransUnion entered the market much later, in 1968, and started business in Canada in 1989. That year, the data these credit bureaus had been collecting—in one case for more than a century—was formalized by an operations research firm called Fair Isaac and Company. Its so-called FICO score—which, in Canada, is called a Beacon score or a Pinnacle—was marketed as a neutral value, the by-product of inputs, a calculation free of opinion. No more credit managers noting the colour of your skin, your marital status, or whether you belong to a church. Just raw data, amassed without comment. Of course, it wasn’t really that simple.

When lenders are deciding whom to loan to, they need to figure out whom they can trust. The credit score is a quick and easy way to make that decision. As private companies, Equifax and TransUnion are regulated both federally and provincially, but key legislation sits with provincial bodies. Credit bureaus do not make recommendations about credit worthiness, though it may seem like they do. Instead, they compile a log of your borrowing history. Every time you apply for a loan or open a credit card, that’s an input on your credit report. A credit bureau analyzes this history and distills your likelihood of meeting financial obligations to a single number. It’s then up to each lender to interpret that number.

According to Borrowell, a company that works with Equifax to help Canadians get copies of their credit reports, the average credit score in Canada is 667. It differs from province to province, but that’s generally considered a “good” score, though the ranges of scores are broad and vary depending on who is doing the lending. One lender might consider 750 to be a “very good” score while another might lower that bar to 725. A higher score—anything close to 900, say—indicates more trust in you as a consumer, and that means better access. You can borrow more money or borrow it at a lower interest rate. A higher score can increase the mortgage you can take out or help you set up utilities. It can also look better to potential employers.

A credit score, at its most basic, is a predictive model of behaviour.

The precise computations for the scores are proprietary. This is partly to stay ahead of competitors. But it’s also because credit bureaus have developed multiple scoring systems. A credit score, at its most basic, is a predictive model of behaviour. Each credit bureau offers different models, and lenders can choose the one that fits their needs. The term “credit score,” in other words, is misleading: it’s actually credit scores, plural. In some cases, they can number in the hundreds.

Think of it like a software program. The credit bureau might release their first version of the program, which calculates a credit score by heavily weighting whether a borrower has a lot of credit products, like several credit cards, a mortgage, and a car loan. For some lenders, that might be the most important factor in their decision to lend to a customer, so they use this original version of the software. But, in version two, the bureau might weight another factor more heavily—for instance, whether the borrower often misses payments. A second lender might prefer that calculation and choose to use version two of the program. This is why you can apply for a credit card and a car loan on the same day and get two different credit scores reported. Credit bureaus have revamped their algorithms so many times that there’s no way of knowing how many scores are currently floating out there under your name.

Credit report data also moves both ways. Lenders take your credit score into account when deciding whether to issue a loan, but they also report information about you back to one or both of the main credit bureaus, typically on a monthly basis. So, if you miss a loan payment, bounce a cheque, or forget to pay a credit card bill, that information gets transferred back to the credit bureaus, and your report is revised. When credit bureaus look to make a new version of the credit score calculation (an update of the software, to continue the metaphor above), statisticians will pull millions of credit reports from a wide spectrum of consumers, trying to see how their predictive equations worked over a set period of time and what they can improve on.

If it sounds complicated, that’s because it is. It’s also up to individual consumers to find mistakes. For Mervin Smith, that mistake was his own name. In 2011, Smith told the CBC that he learned of an unpaid Rogers bill that had been on his report for four years, but the bill was issued to a Marvin Smith. Because of the mistaken debt, he was denied a credit card, a line of credit, and an overdraft on his bank account. For Barbara Hewitt, who teaches at the University of Manitoba, the mistake came from information reported by her bank. In 2020, when the federal government paused student loan payments during the pandemic, her bank erroneously reported that she was delinquent even though it was the bank that had paused her automated payments. As Hewitt told the CBC, her “near perfect” credit score sank immediately.

In fact, you can have an impeccable credit history and still find your score plummeting. In 2019, Robin Harvey made a large purchase on her credit card, close to $15,000. The Toronto resident told Global News that she had recently received an inheritance and had decided to use some of that money on a one-time splurge. She always paid her bills in full every month, and this big purchase was no exception. But her credit score still fell nearly 100 points. Why? The $15,000 charge put her too close to her borrowing limit for the bank’s comfort.

A credit score is not a set figure but an ever-shifting number, and relatively minor mistakes can punish consumers in unforgiving ways. Gabriel Frano checked his credit score regularly, and it always hovered around 750—a very good rating. But, in 2020, when Frano tried to get preapproved for a mortgage on a condo near Woodbridge, Ontario, he was turned down. At the time, Frano told CTV News he was shocked to discover that his credit score had dropped nearly 160 points. After some digging, Frano found the reason: an old credit card he was convinced he had closed had an outstanding balance of ninety-five cents. Even paying off the card wouldn’t help, Frano learned, because his credit report would still list delinquent payments.

Outcomes like these can affect Canadians differently depending on which province or territory they live in. Because credit bureaus are mainly regulated at the provincial level, delinquent payments will stay on your credit report for a different period of time in Prince Edward Island than in Alberta. There are a few consistent policies across provincial lines, mostly to do with who can access your information and for what purpose. But, because complaints about credit report mistakes are made to provincial bodies, there is no federal database compiling them, making it hard to accurately gauge the scale of the problem.

Even credit bureaus struggle to quantify how often mistakes happen in their reports. As Julie Kuzmic, the senior compliance officer of consumer advocacy at Equifax, explains, it’s difficult for the agency to track errors on its own. For one, credit bureaus are dependent on the information they receive from lenders. “It’s not like there is some grand spreadsheet of all the correct names and addresses in Canada, where every time we receive new information, we can check against something.” The other issue is that it can be nearly impossible to know where or how the error crept in. “Somebody might call to get something corrected on their credit report, but whose error was it?” In other words, was it actually an error, such as the teller misspelling your name when opening a line of credit at a bank, or was it fraud—someone using your name illegally? “We can’t really take all the calls that we receive and divide by all the lines of data we have on people’s credit reports and say, ‘Okay, that’s our error rate,’ because you don’t necessarily know what caused the error.” This means credit bureaus roll with the data they get until they’re told otherwise.

The defects of such a system mean that risk assessments—and the social profiling they lead to—can be punitive in ways that are disproportionate to any insight they provide into borrowers. To illustrate this, think of the body mass index calculation. For years, the BMI was seen as a way of using body fat, based on weight and height, to determine health. But, in the last few years, the BMI’s flaws have come to light. The weight ranges have shifted with industry influence, not medical research. The original tests were mainly conducted on white men. And there’s no distinction between fat and muscle mass, leading to super-muscular people (famously, actor Dwayne Johnson) being categorized as obese when they’re plainly not.

The BMI is not an absolute measure of health: it’s just one input a physician can take into account. Yet, for decades, it was trusted nearly implicitly. Despite the wonky science at its core, it helped determine legislation and set insurance premiums. And credit scores? They’re not the sole test of how financially healthy you are. They are just one input, albeit one that’s intrinsically linked with how we see ourselves—and how others see us.

Perhaps the biggest issue with credit scores—more than credit report mistakes, more than the inscrutable way the scores are calculated, even more than the inconsistent way they are applied across lenders—is that they have conditioned us to accept the routine collection and sharing of our private information. While credit scores may not stand out among the algorithms we’re surrounded by, they are one of the oldest forms of consumer surveillance. Surveillance algorithms are everywhere now, tracking how long we watch a video on TikTok or how far we get into reading an e-book. Algorithms on Instagram, for example, don’t even have to trawl for our demographic information and behaviour: we hand it over when we sign up, in exchange for use of the platform. Similarly, Equifax and TransUnion have access to your financial history because your bank, your phone company, and your car-lease provider give it to them. In turn, those same companies buy the aggregate data credit bureaus amass. You are not a credit bureau’s customer—you’re its product.

This raises questions about how effectively credit bureaus safeguard all that information. In January, for example, a $425 million settlement from Equifax was finalized after a 2017 data breach leaked the private information of about 147 million people, leading to surges in identity theft. Companies can also take advantage of consumer data in worrying ways. In 2021, legal firm Wadell Phillips launched a proposed $20 million class action lawsuit against Rogers Communications, alleging that the company regularly performed “soft checks” of customers’ credit information. A soft check isn’t connected to an application for a product, like a cellphone, so it has no effect on the credit score itself. But, according to this suit—which could have millions of claimants—Rogers wasn’t performing these soft checks to investigate legitimate payment queries. Instead, the company is said to have used the information to find other products to market to the customers—which, if true, is a direct contravention of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. The argument hinges on a section of PIPEDA specifying that customers need to give “meaningful consent” for these types of checks. It can’t be some legalese buried in a contract you may never read.

According to Margaret Waddell, the senior lawyer on the lawsuit, the claim alleges that credit bureaus have a habit of giving companies “backdoor access” to all sorts of data. She says that customers have a right to a zone of privacy and that, even if they consent to having their credit checked initially—to start a phone contract, for instance—that doesn’t necessarily mean they consent to ongoing checks for completely different purposes.

Like any consumer surveillance, credit reports also reproduce systemic inequalities. “Even the best consumer algorithm out there still has people who have been historically disadvantaged and are still being punished through algorithms that privilege certain kinds of behaviour and payment history,” says Lauer.

In the United States, a long history of redlining—the practice of banks denying loans to residents of poor, often racialized neighbourhoods—has prevented Black Americans from building up the same generational wealth as white Americans, and on the whole, credit scores reflect that. According to a survey by Credit Sesame, a US credit-monitoring service, more than half of Black Americans have poor credit scores, compared with 37 percent of white Americans. Even more damningly, 30 percent of Black Americans and 25 percent of Latino Americans said that the credit system was stacked against them, preventing them from building good credit, and nearly a third of Black Americans reported that financial providers had misinformed or misled them about how credit worked.

These biases also exist in Canada. Keith Martell, CEO of the First Nations Bank of Canada, says there are several reasons an Indigenous person is more likely to have a lower credit score than a non-Indigenous person. First and foremost, Indigenous people are more likely to experience poverty or have low incomes. Data from the 2016 census shows that 44 percent of people living on reserves have low incomes, compared with just 14 percent of the total population of the country. With a lower overall income, Martell says, it’s not uncommon for poor credit scores to follow—a person who struggles to pay their bills will have those late payments reflected on their credit report. If you have to choose between “eating or paying your power bill,” Martell says, “those things are significant, and they haunt you for a long time.”

According to Martell, physical access to banks or accredited lenders can be more difficult for people in northern or remote areas, which means it’s harder to build up a history of using credit products. Another key piece of the equation, Martell says, is home ownership. “In many First Nations communities, there’s no private home ownership. Often, it’s community housing,” Martell says, noting that, for many living on reserves, the First Nation actually owns their home. Residents may pay the First Nation, but it’s not a traditional mortgage. “Most people get a credit rating when they buy a home. That’s one of the biggest reasons you take a loan.” No mortgage, no input on your credit report.

Without good credit, each step of the financial system becomes more difficult. Giovanni Gallipoli, a professor of economics at the University of British Columbia, believes that access to short-term credit—especially when things go wrong—is crucial to one’s well-being. With certain credit calculations, people living paycheque to paycheque, or people who can’t work, or people with multiple dependents, are often the very group denied money. “If something happens, what are they going to do?” says Gallipoli. “Go back to their family? And if they can’t? It would be horrible.” And, if the government can’t or won’t step in to help people in these dire situations, they are forced to turn to private companies. With low credit scores, their options can be limited to payday loan companies, often described as predatory, or other credit sources with inescapably high interest rates.

No system is perfect, of course, but then, few systems have such disproportionate control over our lives. Despite credit scores resulting from a convoluted scheme of inputs and outputs that requires careful parsing by both algorithms and humans, many people are embarrassed to admit they can’t make sense of their reports—a feeling amplified by a broader culture in which people are reluctant to talk about debt and finances. Being “good” with money is not just a measure of financial credit; it’s tied to social credit as well. A bad score can be downright shameful.

Stacy Yanchuk Oleksy, the CEO of Credit Counselling Canada, a nonprofit that helps dig people out of debt, has seen that shame up close. In her sessions, she tells people that there’s no magic formula to building up a credit score. It takes time and consistent behaviours. Make a payment on your credit card every month, no matter if it’s the minimum balance or the whole bill, as long as it’s consistent. Try not to use more than 50 percent of your available credit on a card at any given time, as your debt-to-credit ratio is a factor in your score. Hold on to credit products for a while; a credit card that you’ve had for years is a stronger element in the calculations than one you opened six months ago. Somehow, customers believe that this knowledge should be innate, something they just absorb intuitively. “If we weren’t born with it, and no one’s taught us, then how are we to know how to do this? And then we get embarrassed because we attach net worth with self-worth.”

The shame of debt, of seeming financial ruin, can “drive people to kill themselves,” says Oleksy, who as a counsellor often had to pull people from the brink. Trained in suicide intervention, she used those skills regularly when speaking with clients. She remembers one man who came in for a session distraught. “He said, ‘If I commit suicide, will my life insurance cover off all my debt?’ So I asked, ‘How much is your debt?’ And he said, ‘$5,000.’ He was willing to kill himself for $5,000.”

Is there a better system? You could pay for everything in cash. But then you would forgo any access to credit in an emergency. The UK has a credit-scoring system similar to that of the US and Canada, but there are actions that citizens can take to improve their credit scores, such as registering to vote. Neither France nor Japan has a formal credit-reporting agency. Instead, credit is mostly dealt with through local banks, with customers showing pay stubs and developing relationships with lenders. The risk of being trapped in cycles of debt and repayment is why some believe access to credit should be a basic human right. In the 1970s, Muhammad Yunus began offering small interest-free loans to people in impoverished areas of Bangladesh, a microcredit system that has since been copied in other developing countries.

In 2019, US Democratic leadership candidate Bernie Sanders proposed abolishing privately run credit bureaus and replacing them with a free government-run registry devoted to the accuracy of consumer data. Brenda Spotton Visano, a professor of economics and public policy at York University, says there could be a middle ground between a fully privatized credit system and a fully public one. Perhaps there are products that credit scores shouldn’t influence, like a basic bank account with overdraft protection. Spotton Visano argues that overdraft service should be available to all Canadians, regardless of credit score. In this hypothetical system, that basic bank account would be a federal guarantee, with the credit score kicking in for bigger purchases and loans. “Your credit score affects your ability to buy a house. Is that something you want regulated? What about rentals?” Spotton Visano asks. Should your credit score affect your ability to get housing at all? How should federal regulation come into play there? “If it affects your ability to even get basic accommodation, then yes, I would want some sort of oversight on those industries.”

After years of waging battle with TransUnion, Angela Monaghan is still opting in to the system. She deliberately holds a small mortgage on her house and still shops with a credit card. She says that, despite what she’s been through, she still wants to keep the credit score she’s worked hard to restore at its excellent rating. And, really, what alternative does she have? There’s no good way around it. Participation in the credit system is essentially mandatory, and consumers are at its mercy.