Though sci-fi movies would have us believe that space is incredibly cold — even freezing — space itself isn't exactly cold. In fact, it doesn't actually have a temperature at all.

Temperature is a measurement of the speed at which particles are moving, and heat is how much energy the particles of an object have. So in a truly empty region of space, there would be no particles and radiation, meaning there's also no temperature.

Of course, space is full of particles and radiation to produce heat and a temperature. So, how cold is space? Is there any region that is truly empty, and is there anywhere that the temperature drops to absolute zero?

Related: What is the coldest place in the universe?

How stars are heating up space

- Stars as heat sources: Nuclear fusion inside stars generates vast amounts of energy

- Radiation warms matter: Heat increases when stellar radiation interacts with particles

- Particle density matters: Regions with more matter retain heat more effectively

The hottest regions of space are immediately around stars, which contain all the conditions to kick-start nuclear fusion.

Things really warm up when radiation from a star reaches a spot in space with a lot of particles. This gives the radiation from stars like the sun something to actually act upon.

That's why Earth is a lot warmer than the region between our planet and its star. The heat comes from particles in our atmosphere vibrating with solar energy and then bumping into each other, distributing this energy.

Proximity to our star and possessing particles are no guarantee of warmth, though. Mercury — closest to the sun — is blisteringly hot during the day and frigidly cold at night. Its temperatures drop to a low of 95 Kelvin (-288 °Fahrenheit/-178 °Celsius ).

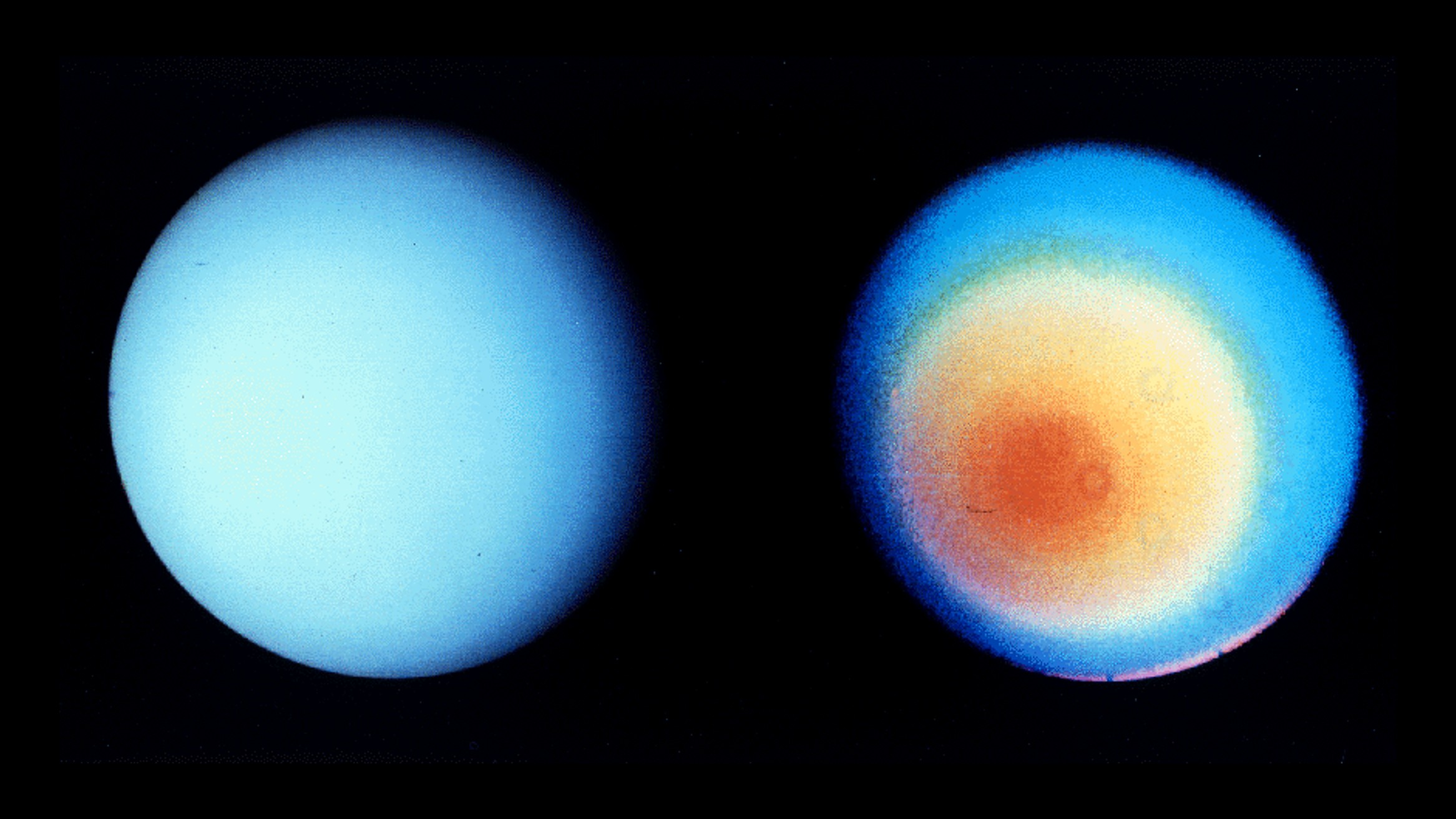

Temperatures dip to -371°F (-224 °C) on Uranus, making it even colder than on the furthest planet from the sun, Neptune, which has a still incredibly cold surface temperature of -353°F (-214 °C ).

This is a result of a collision with an Earth-sized object early in its existence, causing Uranus to orbit the sun on an extreme tilt, making it unable to hang on to its interior heat.

Far away from stars, particles are so spread out that heat transfer via anything but radiation is impossible, meaning temperatures radically drop. This region is called the interstellar medium.

The coldest and densest molecular gas clouds in the interstellar medium can have temperatures of 10 K (-505 °F/-263 °C), while less dense clouds can have temperatures as high as 100 K (-279 °F/-173 °C).

What is cosmic background radiation?

- Cosmic microwave background (CMB): Radiation left over from the early universe

- Uniform temperature: Measures about 2.7 kelvins above absolute zero

- Oldest light: Formed around 400,000 years after the Big Bang

The universe is so vast and filled with such a multitude of objects, some blisteringly hot, others unimaginably frigid, that it should be impossible to give space a single temperature.

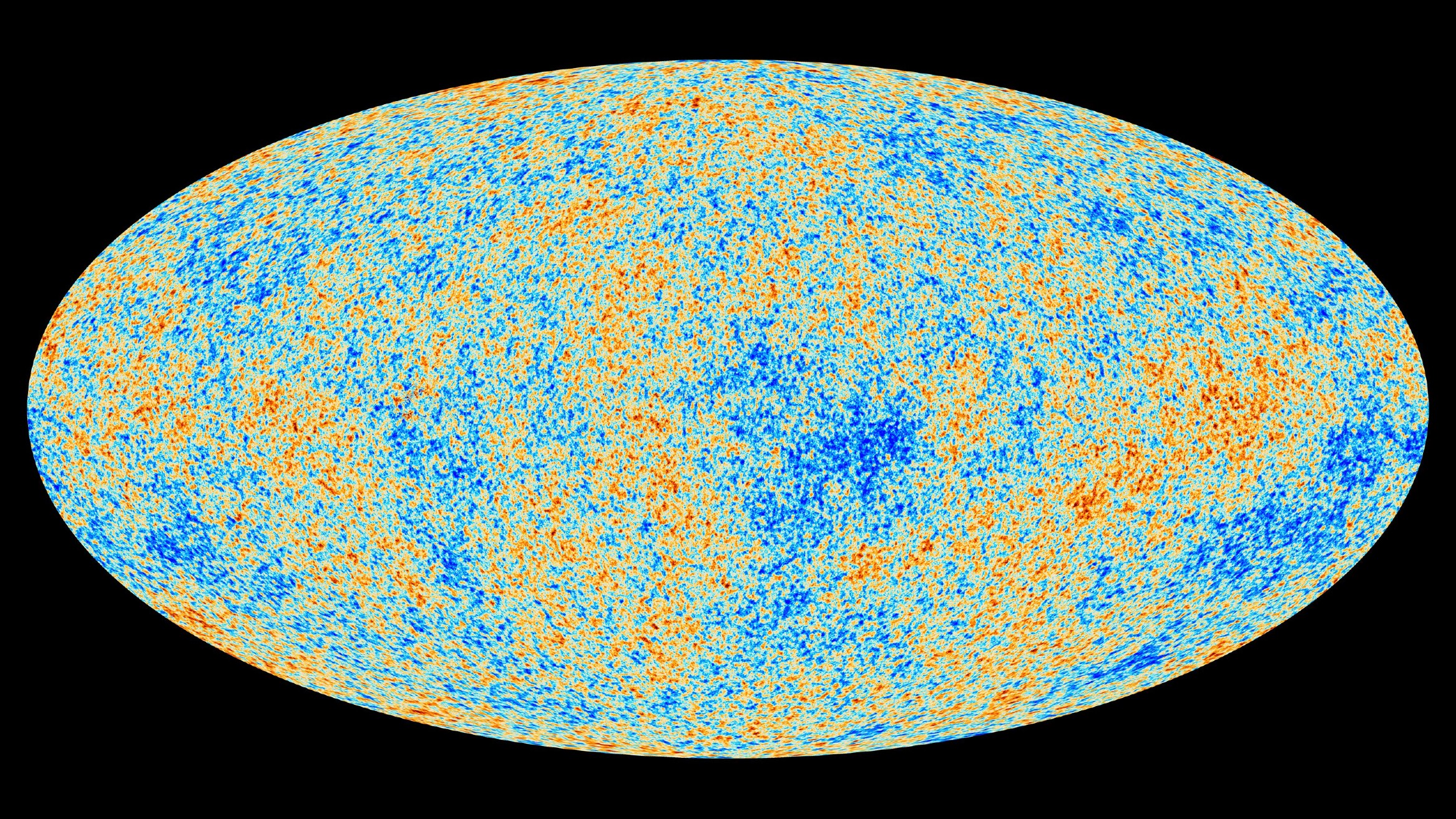

Yet, there is something that permeates the entirety of our universe with a temperature that is uniform to 1 part in 100,000. In fact, the difference is so insignificant that the change between a hot spot and a cold spot is just 0.000018 K.

This is known as the cosmic microwave background (CMB) and it has a uniform temperature of 2.7 K (-459°F/-270°C). As 0 K is absolute zero, this is a temperature just 2.725 degrees above absolute zero.

The CMB is a remnant leftover from an event that occurred just 400,000 years after the Big Bang called the last scattering. This was the point when the universe ceased to be opaque after electrons bonded to protons, forming hydrogen atoms, which stopped electrons from endlessly scattering light and enabling photons to freely travel.

As such, this fossil relic "frozen in" the universe represents the last point when matter and photons were aligned in terms of temperature.

The photons that make up the CMB weren't always so cold, taking around 13.8 billion years to reach us. The expansion of the universe has redshifted these photons to lower energy levels.

Originating when the universe was much denser and hotter than it is now, the starting temperature of the radiation that makes up the CMB is estimated to have been around 3,000 K (5,000° F/ 2,726°C).

As the universe continues to expand, that means space is colder now than it's ever been and it's getting colder.

What would happen if you were exposed to space?

- No instant freezing: Heat loss in space happens slowly

- Heat transfer limits: Only radiation can remove heat in a vacuum

- Primary danger: Rapid decompression occurs before freezing

If an astronaut were left to drift alone in space then exposure to the near-vacuum of space couldn't freeze an astronaut as often depicted in science fiction.

There are three ways for heat to transfer: conduction, which occurs through touch; convection, which happens when fluids transfer heat; and radiative, which occurs via radiation.

Conduction and convection can't happen in empty space due to the lack of matter and heat transfer occurs slowly by radiative processes alone. This means that heat doesn't transfer quickly in space.

As freezing requires heat transfer, an exposed astronaut — losing heat via radiative processes alone — would die of decompression due to the lack of atmosphere much more rapidly than they freeze to death.

Additional resources

For more information about the properties of space, check out "Astrophysics for People in a Hurry" by Neil deGrasse Tyson and "Origins of the Universe: The Cosmic Microwave Background and the Search for Quantum Gravity" by Keith Cooper.

Bibliography

- Harvard University, "The human body in space: Distinguishing facts from fiction", July 2013.

- NASA, "Fluctuations in the Cosmic Microwave Background", accessed July 2022.

- NASA, "Cosmic Microwave Background", July 2022.

- NASA, "Eta Carinae", September 2020

- Paul Sutter, "You Will Not Freeze To Death In Space", Forbes, April 2019.