Paul Rusesabagina is perhaps one of the world’s best known Rwandans. His actions during the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi were made famous in the 2004 Hollywood film Hotel Rwanda.

The film was inspired by what happened inside Hotel des Mille Collines in the capital, Kigali. Here, 1,268 Rwandans, both Tutsis and Hutus, were saved from genocidal forces waiting beyond its walls.

The film depicts Rusesabagina – who left Rwanda in 1996 – as a hero who saved these lives. Following the film’s release, Rusesabagina received several humanitarian awards, including the US Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005 from former president George W Bush. He eventually became a US resident and Belgian citizen.

On 27 August 2020, however, Rwandan officials arrested Rusesabagina. Human Rights Watch accused the Rwandan government of intentionally misleading him into a flight to Kigali.

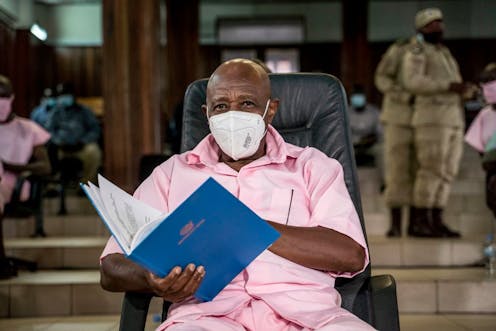

The government accused Rusesabagina of supporting anti-Rwanda groups. He was charged with terrorism, arson, kidnapping and murder over two attacks in 2018 that killed nine Rwandans. On 20 September 2021, Rusesabagina was convicted of these charges. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Since his conviction, Rwanda has rebuffed growing international pressure for Rusesabagina’s release.

In August 2022, during a visit to Kigali, US secretary of state Antony Blinken urged the government to release Rusesabagina. In Hollywood, actors and actresses have highlighted the issue through a “Free Rusesabagina” clothing campaign.

Read more: The US and Rwanda: how the relationship has evolved since the 1994 genocide

In my most recent research paper, I focused on the Rusesabagina case. Based on interviews with Rwandans, I conclude that Hollywood’s interpretation of historical events significantly differs from those who lived in the hotel during the genocide.

Hotel Rwanda is a double-edged sword for the country.

On one hand, it introduced the horrific 1994 genocide to a world that knew little of what had happened in the small African nation. Over 100 days between 6 April and 19 July, Rwanda witnessed the deaths of up to one million Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

On the other hand, the film’s historical inaccuracies built up Rusesabagina’s profile. Based on what I found during the course of the interviews I did, I argue that he used his fame to promote his version of Rwandan history and his desire for political power. My research findings echo those of others, including Rwandan academics, who have explored the mismatch in narratives.

Many in the global north, whose primary knowledge of Rwanda consists of the film, were swayed to Rusesabagina’s rather than Rwandans’ expression of their history, goals and desires. This narrative was driven to a large extent by human rights groups, which have been highly critical of the country’s human rights record.

Differing narratives

Between 2008 and 2018, more than 100 Hotel des Mille Collines survivors discussed with me their historical experiences and belief that Rusesabagina was not the reason they were still alive. I conducted most of these interviews at the hotel and the Kigali Genocide Memorial, which houses the remains of more than 250,000 genocide victims. My research also used existing networks within the Rwandan government and civil society organisations.

Survivors who were at the hotel said Rusesabagina ran the hotel as a personal profit-making venture.

If one could not pay him, one would face expulsion from the hotel’s grounds, which meant certain death. One survivor said:

If you could pay, you would stay in a room. If you couldn’t pay for a room, you could pay to stay in a hallway. If you couldn’t pay that, you could pay to stay by the pool. If you couldn’t pay that, he (Rusesabagina) would demand you to leave.

One hotel worker told me this:

He (Rusesabagina) didn’t care about any of us (workers). I begged him to let them (my family) stay as I was working there (at the hotel) for a long time. He didn’t care and demanded I pay him money or he would throw them out to be killed.

Several other survivor stories suggest a different narrative from the one in the film. In Hotel Rwanda, Rusesabagina is depicted as collecting money only to pay off genocide perpetrators.

Rusesabagina during the genocide

Prior to the genocide, Rusesabagina worked at the neighbouring Hotel des Diplomates. He took over the management of Hotel des Mille Collines after discovering that its European manager, Bik Cornelis, had been evacuated. One former hotel worker told me:

…a few days into the killings, Rusesabagina walked in one day and saw that the old manager (Cornelis) was taken with the other Europeans. He called (the hotel owners) and told them to … only work with him. They had no idea what was going on and probably hadn’t talked to Cornelis yet, so they agreed.

While the film credits Rusesabagina with creating an oasis during the conflict, he’s not the reason the hotel – one of the few areas offering refuge at the time – survived attacks from those behind the genocide.

Not depicted in the film are the seven to 10 United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR) soldiers who were constantly positioned in front of the facility.

In his book, Roméo Dallaire, a former commander of this UN mission, says he stationed troops at the hotel’s only entrance as a symbolic indication that it was under the UN’s protection. Dallaire has spoken out against Hotel Rwanda as historical revisionism.

Further, the Interahamwe, the primary Hutu death squads responsible for the genocidal killings, had been directed to stay outside the walls of the hotel. They allowed people to run into it, but would threaten or kill those who tried to leave.

One former Interahamwe who had been stationed about 20 metres from the hotel’s entrance told me that he received instructions from his regional commander to “just stay put by the hotel and to allow the Tutsis and others to have access”. The hotel was also used for prisoner exchanges “and it would be the final spot for us to cleanse (murder the Tutsis) once we beat the RPF (Rwandan Patriotic Front)”.

The Rwandan Patriotic Front, led by Paul Kagame, took control of the country in July, ending the genocide. The horrors of the 100-day period led to Rwanda’s focus on forming a new single ethnic identity: “Rwandan”.

Jonathan Beloff receives funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.