Tributes for Biz Markie have flooded the web since the rapper’s wife announced his death at 57 years old last Friday. Multiple headers highlight Biz as a “rapper, actor and comedian,” and center his 1989 Top 10 hit “Just a Friend.” But Marcel Theo Hall was anything but a one-hit wonder. A proper ID would name him “Rap OG, Inhuman Orchestra, DJ, sneaker head, avid collector” with an option for several more descriptors. Biz was more than just the Clown Prince of hip-hop. The measure of his impact is known by industry insiders, his peers, friends, and the DJs who studied and learned from him in the music industry. Questlove gave Biz credit on an IG post for his renowned crate digging, collecting and sample nerdom. “Biz built me man,” he wrote. “In my early early stages it was Biz who taught me the REAL places to cop records….Biz taught me what cities had good digging…..Biz taught me where to collect 45s……Biz taught me where to collect 8TRACK TAPES!!” But Biz’s public legacy outside of hip hop has been largely contained to one of the most infectious sample loops and hooks ever.

“I’m one of them unsung heroes,” he told The Washington Post in 2019. “It’s like, I’m part of hip-hop, but sometimes I’m forgotten about in hip-hop.” His footprints, however, can easily be found across the last 35 years — if you know where to look.

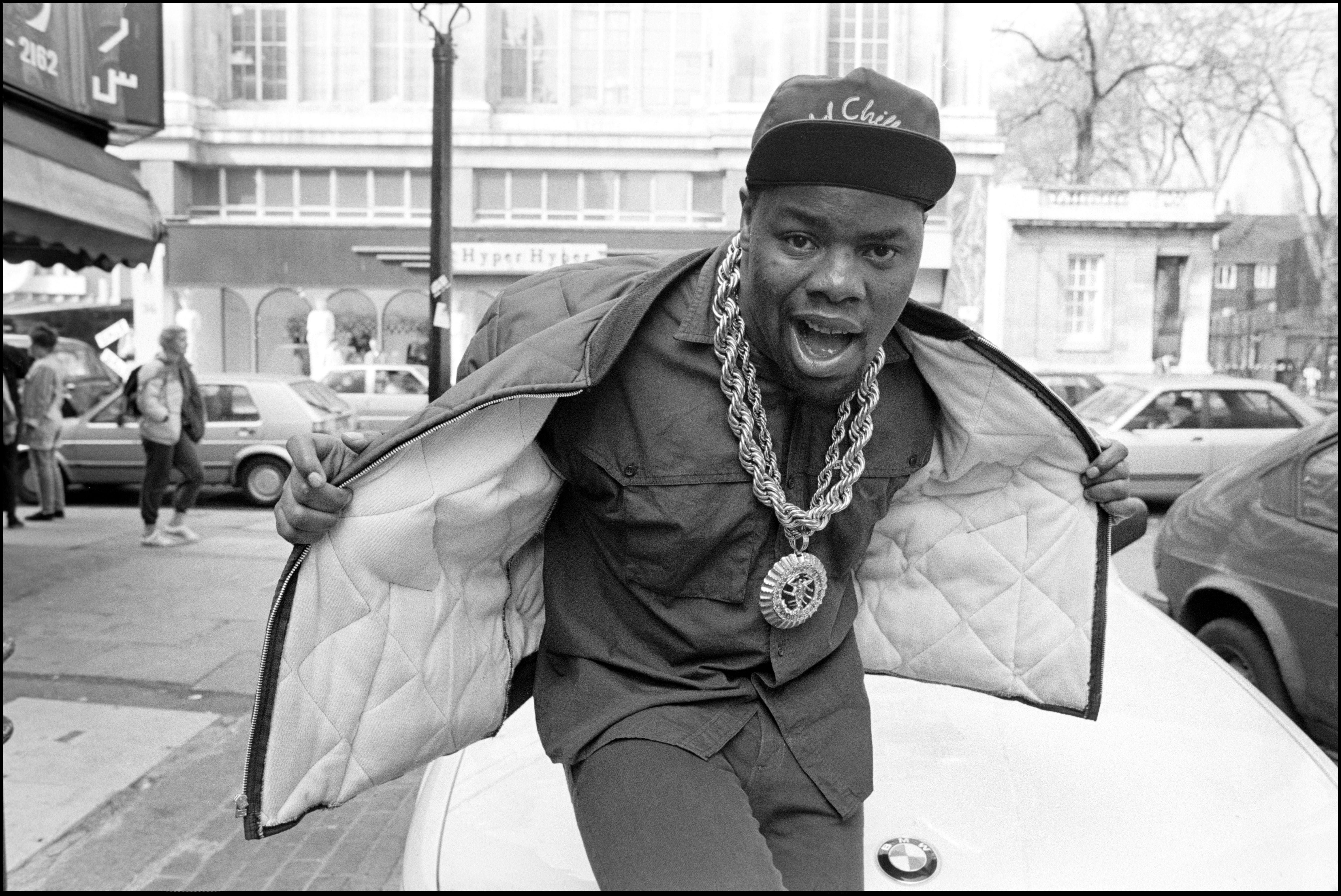

The moniker “The Clown Prince of Hip-Hop” was bestowed upon Biz lovingly, but without historical context it might suggest he was a novelty act. In reality, The Diabolical Biz Markie hails from the Justice League of rap collectives: Queensbridge’s legendary Juice Crew (the Avengers would be Wu-Tang in this analogy). The group’s founder, DJ Mr. Magic, helmed NYC’s first all hip-hop show on a top radio station with protegé Marley Marl (as in “Every Saturday, Rap Attack. Mr. Magic, Marley Marl”). Juice Crew members are now all considered originators, each with a specialty: MC Shan, who led the group into one rap’s most historical rivalries; Big Daddy Kane, master of lyrical dexterity and flow; Roxanne Shanté, who was holding her own battling guys years older at just 14 years old; Kool G Rap, widely recognized as the godfather of mafioso rap; and Biz Markie, Kane’s creative partner since the two met in a rap battle at Albee Square Mall, was the lighter side with comic relief, energy and beatbox back up.

The combination of Marley Marl’s production, Kane’s pen as a co-writer, and Biz’s energy represented the essence of classic hip-hop: legendary DJing and production skills, catchy lyrics and storytelling, delivered with energy that kept the crowd engaged. Biz was party hip-hop: the class clown turned MC with stories that pulled you in, made you laugh, and supplied quotables that would be all over IG and Twitter if the music came out today. This is why “Just a Friend” transcends era and genre. But skipping to “Just a Friend” in Biz’s story does him a disservice. It was Biz’s sole crossover hit, but he has multiple singles with arguably bigger cultural significance. Hit play on the album Biz’s Baddest Beats, Biz Markie’s version of a greatest hits, and you’ll recognize the source material for classics from Nas, Biggie, Wu Tang, A Tribe Called Quest, Mary J Blige, and on and on (that was a Biz reference, FYI). Even West Coast artists like Ice T, Ice Cube and Eazy E pulled from Biz songs, and he’s among the great rap storytellers Snoop has paid homage to through covers. Your favorite rappers additionally put Biz on their records because his energy was impossible to duplicate. Jay-Z’s “Girls Girls Girls” wouldn’t be the same without Biz’s signature off-key, sing-songy vocals on the hook.

Biz’s own crossover career hit a decline after “Just a Friend” thanks largely to a roadblock with his third studio album, 1991’s I Need a Haircut. Sample clearance protocols were still murky, often settled out of court. That all changed after Gilbert O’Sullivan sued Biz and his label Warner over the single “Alone Again.” It may have gone away with a settlement, as De La Soul’s suit with rock band The Turtles had earlier that year, had the single and album been released without seeking clearance in the first place. But because O’Sullivan had actually received and denied a request, the judge decided to make an example, awarding $250,000 in damages, forbidding sales of the album with the single on it, and going so far as to suggest criminal charges. Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records Inc. did away with any gray area in sample usage and clearance, no matter how small; approval had to be obtained prior to commercial release. This suit is the reason why a song like Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power,” which stacked so many loops and samples that even producers Hank and Keith Shocklee don’t remember them all, will never happen again. Hip-hop, which was birthed from cutting/sampling existing records, immediately became both a more litigious space, and a more expensive one.

Biz returned in 1993 with the tongue in cheek All Samples Cleared, but by then hip-hop was moving away from the party boom-bap that Biz specialized in, instead turning towards west coast G Funk, followed by sounds from the south. Casual fans may think Biz mostly disappeared after that, but he was always on the scene. He was consistently DJing, and in addition to periodic resurgent moments like R&B singer Mario’s “Just a Friend” in 2002 and pop star Austin Mahone’s “Say You’re Just a Friend” ten years later, Biz would pop up in a myriad of pop culture spaces over the years. He played the uglier sister to Jamie Foxx’s Wanda on In Living Color; he and Will Smith turned beat-boxing into a language and had a dialogue in Men in Black II; he gave a baby shark the business in Sharknado 2; he voiced roles on Crank Yankers and Adventure Time; he even taught kids how to beatbox as a recurring character on Yo Gabba Gabba.

Biz was all about playful, lighthearted fun. He was a person who’d decided to enjoy the ride, and you’d be hard-pressed to find any negative feedback about him. Stories all confirmed that he was a child at heart, like the Beastie Boys sharing with Desus & Mero that Biz always had to have candy in the studio. He was also a collector of collections. If you could amass a quantity of an item, Biz had it: trading cards, posters, magazines, lunchboxes. Myths about the storage needed to house his many collections have ranged from two rooms to two homes. He’s heralded as one of the original sneakerheads, with a collection nearing 6,000 pairs in 2019, despite him giving away roughly 500 pairs a year. But in the early 2000s he shared with VIBE that his collection numbered “in the five figures.” He’s credited as one of the figures who drove Nike’s transition from running shoe to lifestyle brand by sporting the then mid-selling Nike Air Safaris on the back cover of 1988’s Goin’ Off. And he had a signature shoe with Pro Keds in 2011. His penchant for collecting obviously translated to vinyl, including an extensive collection of 45s which he played on the only pair of Technic 7” turntables in the world. But after a 2012 appearance on Celebrity Househunting to find a home with enough room to properly store and display all this things, the internet honed in on Biz’s museum-worthy toy collection, which included Beanie Babies, action figures, Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots, every board game ever made, and his self-proclaimed “treasure,” every Barbie doll from release to present. Biz was Josh Baskin in BIG… but Black...and from Long Island...and actually grown.

Biz’s story, fortunately, doesn’t close on a note of regret or lack of acknowledgement. Fans have poured out love consistently while standing a passive vigil for him since 2020, when news broke that his health had declined after a long battle with diabetes. Prior to that, however, Biz was always beloved and embraced by the hip-hop community, old and young=. He was always present — again, if you knew where to look. And he wasn’t trippin’ about not having another career Hot 100 chart topper. In conversation about the 30th anniversary of “Just a Friend” in 2019, Entertainment Weekly asked Biz how he felt about being labeled a one-hit wonder. “I don’t feel bad,” he confirmed. “I know what I did in hip-hop.”