It’s official: the Great Barrier Reef is suffering its fourth mass bleaching event since 2016. We dived into the reef yesterday and saw the unfolding crisis firsthand.

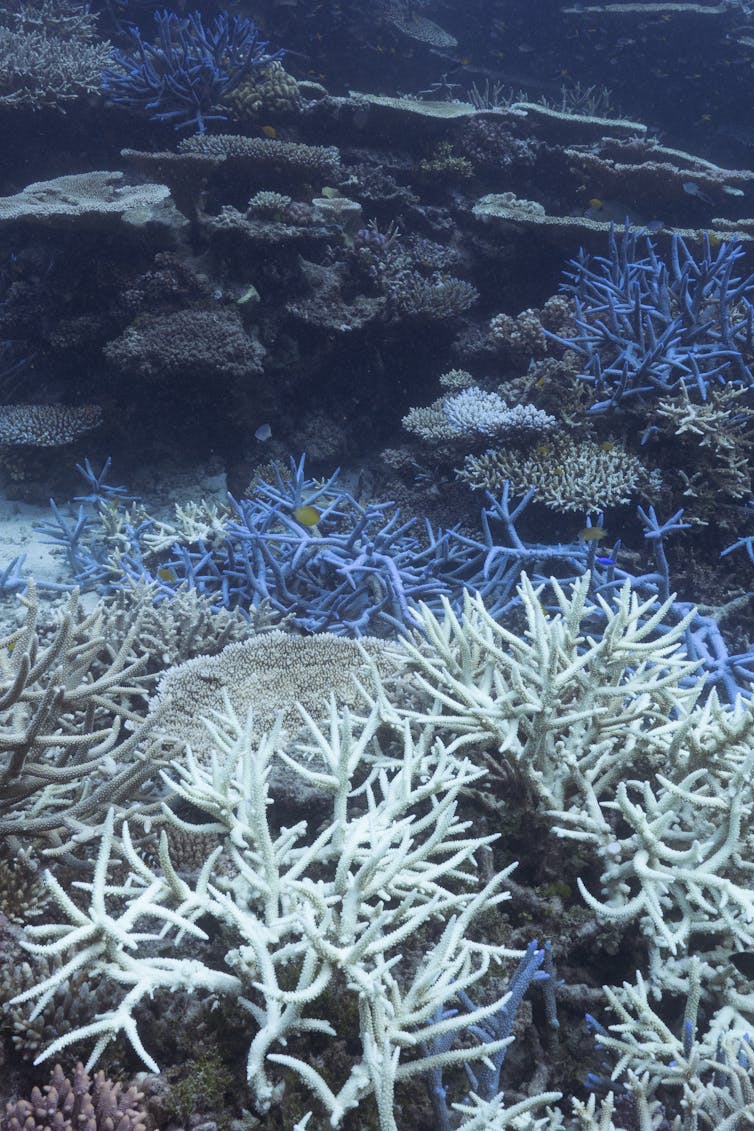

Descending beneath the surface at John Brewer Reef near Townsville, our eyes were immediately drawn to the iridescent whites, blues and pinks of stressed corals among the deeper browns, reds and greens of healthier colonies.

It’s a depressing, but all-too-familiar feeling. A sense of: “here we go again”

This is the first time the reef has bleached under the cooling conditions of the natural La Niña weather pattern, which shows just how strong the long-term warming trend of climate change is. Despite the cooling conditions, 2021 was one of the hottest years on record.

When coral bleaches, it is not dead – yet. Coral reefs that suffer widespread bleaching can still recover if conditions improve, but it’s estimated to take up to 12 years. That is, if there’s no new disturbance in the meantime, such as a cyclone or another bleaching event.

So what conditions are needed for coral recovery? And under what conditions will coral die?

What it takes for coral to die

Whether a coral can survive bleaching depends on how long conditions remain stressful, and to what level. What’s more, some species are more sensitive than others, such as branching acropora corals, especially if they’ve bleached previously.

If water remains too warm for too long, corals will eventually die. But if the water temperature drops and the ultraviolet light becomes less intense, then the coral may recover and survive.

While the average sea temperatures in the reef currently remain above average, they’ve shown signs of cooling to a more amenable average for coral survival.

Sea temperatures in Cleveland Bay, near Townsville, were above 31℃ in early March, but thankfully have now reduced to below 29℃. Similarly in the Whitsundays, Hardy Reef experienced temperatures as high as 30℃ but has receded to nearer 26℃ in the past few weeks.

If coral does survives a bleaching event, it is still impacted physiologically, as bleaching can slow growth rates and reduce reproductive capacity. Surviving colonies also become more susceptible to other challenges, such as disease.

Signs of stress

Survival also depends on each individual coral’s own resilience: its ability to cope with higher temperatures and increased ultraviolet stress.

For example, fast growing branching corals are the most susceptible to bleaching and are generally the first to die. Long-lived massive corals, such as porites, may be less susceptible to bleaching, show minimal effects of bleaching and recover quicker.

Corals can use fluorescent pigments to shield themselves from excessive ultraviolet radiation – a bit like sunscreen that lets coral manage, filter and attempt to regulate the incoming light.

To the casual observer, fluorescent corals look bright purple, pink, blue and yellow. For reef scientists, fluorescence is an obvious signal that corals are stressed and struggling to regulate their internal balance. As we’ve seen, white and fluorescent corals are currently a common sight on many reefs.

À lire aussi : Adapt, move, or die: repeated coral bleaching leaves wildlife on the Great Barrier Reef with few options

Most coral species have fluorescent pigments in their tissue. Some are always visible to humans, especially branching corals with bright blue or pink hues on the their branch tips.

Others are never visible, and some are visible only during times of heat stress when coral colonies boost these fluorescent pigments to fight the increasing ultraviolet intensity in warmer seas.

Coral can’t adapt fast enough

Scientists measure heat stress on corals using a metric called “degree heating weeks”.

One degree heating week is when the temperature at a given location is more than 1℃ over the historical maximum temperature. If the water is 2℃ above the historical maximum for one week, this would be considered two degree heating weeks.

Generally speaking, at four degree heating weeks, scientists expect to see signs of stress and coral bleaching. It usually takes eight degree heating weeks for coral to die.

According to Bureau of Meteorology data, many parts of the Great Barrier Reef, such as off Cairns and Port Douglas, currently remain in the window of between four and eight degree heating weeks. But some areas, near Townsville and the Whitsundays, are experiencing severe bleaching stress beyond eight degree heating weeks.

While we hope many coral reefs will recover from this round of bleaching, the long term implications cannot be understated.

When corals bleach, they eject their zooxanthellae – single-celled algae that gives coral colour and energy. Some corals may regain their zooxanthellae after the bleaching event is over, but this usually takes between three and six months.

À lire aussi : No, sunscreen chemicals are not bleaching the Great Barrier Reef

To make matters worse, full reef recovery requires no new bleaching events or other disturbances in the years that follow. Given the reef has bleached six times since the late 1990s, alongside global climate trajectories, this would appear an unlikely scenario.

While some corals may learn to cope with these new conditions by potentially acquiring more heat-tolerant zooxanthellae, the reality is that change is happening too fast for coral to adapt via evolution.

The severe bleaching in previous years also means future events may appear less severe. But this is simply because most of the heat sensitive corals have already died, potentially resulting in a lower probability of widespread severe bleaching.

We need stronger climate policies and action

Australia has the world’s best marine scientists and marine park managers. And yet, our policies are rated “highly insufficient”, according to the latest Climate Action Tracker.

If global emissions continue unabated, Australia may warm by 4℃ or more this century. Under this scenario, widespread coral bleaching is likely on the Great Barrier Reef every year from 2044 onward.

There has been some glimmers of hope in federal policy in recent years, such as statements recognising the existential threat climate change poses to coral reefs. Despite this recognition, substantial action is lacking, as any policy without action on climate change is ineffective.

If the federal government, reef businesses and individuals are to show leadership and maintain healthy reefs, we need to work together and take rapid, drastic action to reduce carbon emissions.

Committing to a stronger emissions target for 2030 and a carbon neutral footprint for all Great Barrier Reef businesses would go a long way to exhibiting the kind of change required if coral reefs, in their current form, are to survive into the future.

À lire aussi : Climate change has already hit Australia. Unless we act now, a hotter, drier and more dangerous future awaits, IPCC warns

Adam Smith receives funding from Australian and Queensland Government and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.

Nathan Cook is co-chair of the Australian Coral Restoration Consortium, a regional group of the Coral Restoration Consortium.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.