Hollywood actors went on strike on July 14, joining film and television writers who have been on the picket lines since May. It’s the first time actors and writers have picketed together since 1960, when Ronald Reagan was the president of the Screen Actors Guild.

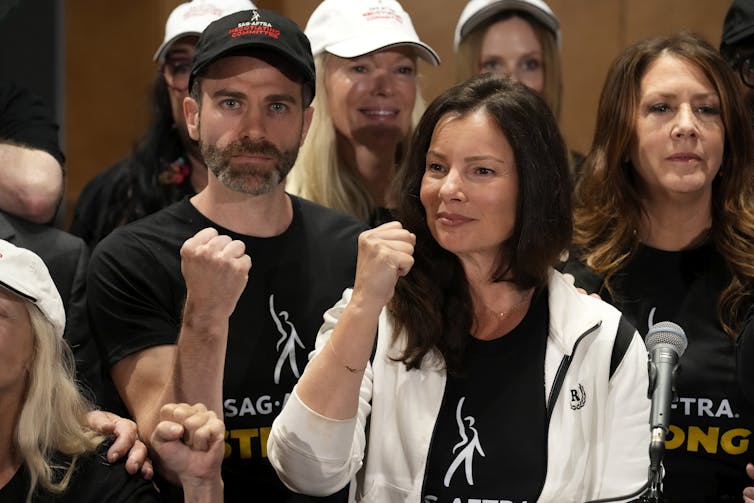

Following failed talks with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) announced the strike at a press conference on July 13.

At the heart of the negotiations between the union and the guild are two key issues: residual payments in the streaming era and the ownership of an actor’s likeness if it’s reproduced by artificial intelligence. The union is calling for fairer pay splits and tighter AI regulations over these issues.

This strike is a watershed moment for the entertainment industry, marking a turning point for the future of labour in the arts. But it will also have widespread impacts on the film and television industry beyond the United States, and Canada is bracing for impact.

‘Cataclysmic’ issues at stake

The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists released a statement last week in solidarity with SAG-AFTRA: “[U.S. actors’] issues are our issues and performers deserve respect and fair compensation for the value they bring to every production.”

These issues are “cataclysmic,” according to Canadian actor and producer Julian De Zotti. De Zotti and I discussed these issues as part of a greater conversation on the future of entertainment in the ongoing CTRL ALT DISRUPT series, organized by Artscape Daniels Launchpad and the City of Toronto’s Creative Technology Office.

He says the issues being negotiated are existential for creators the world over:

“We are at a seismic inflection point in the industry, as a massive technological shift is changing how working and middle class artists, actors, writers, craftspeople can make a sustainable living in the entertainment industry.”

To be clear, it’s not the technology itself creators are taking issue with. When it comes to AI, many film industry professionals are already using tools like ChatGPT and Midjourney to help flesh out the background for scripts or develop visual worlds and imagery for pitch decks.

De Zotti, who has won the Canadian Screen Award for Best Web Program or Series for the past two years, is already integrating AI tools into his practice. He is not afraid of new technology, but rather, how it might be misused.

An existential threat

AI poses a threat for actors in particular because their livelihoods depend on their identity. There need to be specific guardrails and parameters established that protect artists, their creations and their image. They must have a say in how their work and image are used and receive fair compensation for it.

Technology advances quickly, sometimes outpacing our ability to fully comprehend its repercussions before adopting it. The strike offers the opportunity to press pause on the otherwise unbridled adoption of disruptive AI technology.

“This can’t be like social media where the technology came too fast and there were no clear guidelines on its use, and now it’s completely out of control,” says De Zotti.

Instead of scrambling to play regulatory catch-up after damage has been done, considerations need to be made at the outset to avoid damaging consequences, intended or not.

What the strike means for Canada

During the strike, service production, which represents a majority of the $11.69 billion annual work done in Canada, will come to a halt. All American productions — from big budget blockbusters like Star Trek, which shoots in Toronto, to indie feature films using SAG actors — will be affected.

This will, in turn, have a direct effect on the 244,000 people who work in the film and television industry in this country. But it might also open up a different business model, that, as De Zotti points out, “doesn’t rely on you to package your show or movie with stars to get it made.”

While the streaming issue under negotiation is centred around residuals and compensation, Canadian content creators face additional struggles.

Read more: How the Online Streaming Act will support Canadian content

Streaming companies have set up shop in Canada for a few years now, promising to make shows led by Canadians. However, De Zotti says this has not been the case. “It’s been a mirage. Bill C-11 is supposed to change all that, but that is still yet to be seen.”

However, if the strike lingers, perhaps markets outside of Canada will look to acquire Canadian content, as is already the case with the CW, which turned to Canadian content to fill its fall schedule.

Is this Canada’s moment?

Perhaps this strike is a moment for Canada to rise to the occasion; while the Canadian entertainment industry can’t compete with the sheer scale or spending power of Hollywood, it is in this environment of massive change that we shine as scrappy, creative disruptors.

From Norman McLaren’s experimental work with the NFB, through the rise of interactive documentaries, to the explosion of game-based virtual concerts, Canada has always been seen as an innovator in entertainment.

As for the strike itself, its outcome will surely set a precedent. Whatever guidelines the WGA and SAG establish with the studios will be used as a template when it’s time for Canadian unions to negotiate.

The reality is, AI and streaming are not technologies of tomorrow; both are here to stay. As the dust settles south of the border, we have the chance to not just sit back and wait, but to lead by example.

We have the opportunity to not only create unimagined new forms of storytelling, but also experiment with fairer business models rooted in transparent data and more equitable ways of using the powerful tools that threaten to upend the industry of yesterday.

Ramona Pringle has received funding from the Canadian Media Fund, Ontario Creates and the Bell Fund. She is affiliated with the City of Toronto’s Film Television and Digital Media Board, Artscape Daniels Launchpad, and Interactive Ontario.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.