Have you ever heard something that others cannot – such as your name being called? Hearing voices or other noises that aren’t there is very common. About 10% of people report experiencing auditory hallucinations at some point in their life.

The experience of hearing voices can be very different from person to person, and can change over time. They might be the voice of someone familiar or unknown. There might be many voices, or just one or two. They can be loud or quiet like a whisper.

For some people these experiences are positive. They might represent a spiritual or supernatural experience they welcome or a comforting presence. But for others these experiences are distressing. Voices can be intrusive, negative, critical or threatening. Difficult voices can make a person feel worried, frightened, embarrassed or frustrated. They can also make it hard to concentrate, be around other people and get in the way of day-to-day activities.

Although not everyone who hears voices has a mental health problem, these experiences are much more common in people who do. They have been considered a hallmark symptom of schizophrenia, which affects about 24 million people worldwide.

However, such experiences are also common in other mental health problems, particularly in mood- and trauma-related disorders (such as bipolar disorder or depression and post-traumatic stress disorder) where as many as half of people may experience them.

Why do people hear voices?

It is unclear exactly why people hear voices but exposure to prolonged stress, trauma or depression can increase the chances.

Some research suggests people who hear voices might have brains that are “wired” differently, particularly between the hearing and speaking parts of the brain. This may mean parts of our inner speech can be experienced as external voices. So, having the thought “you are useless” when something goes wrong might be experienced as an external person speaking the words.

Other research suggests it may relate to how our brains use past experiences as a template to make sense of and make predictions about the world. Sometimes those templates can be so strong they lead to errors in how we experience what is going on around us, including hearing things our brain is “expecting” rather than what is really happening.

What is clear is that when people tell us they are hearing voices, they really are! Their brain perceives voice experiences as if someone were talking in the room. We could think of this “mistake” as working a bit like being susceptible to common optical tricks or visual illusions.

Coping with hearing voices

When hearing voices is getting in the way of life, treatment guidelines recommend the use of medications. But roughly a third of people will experience ongoing distress. As such, treatment guidelines also recommend the use of psychological therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy.

The next generation of psychological therapies are beginning to use digital technologies and virtual reality offers a promising new medium.

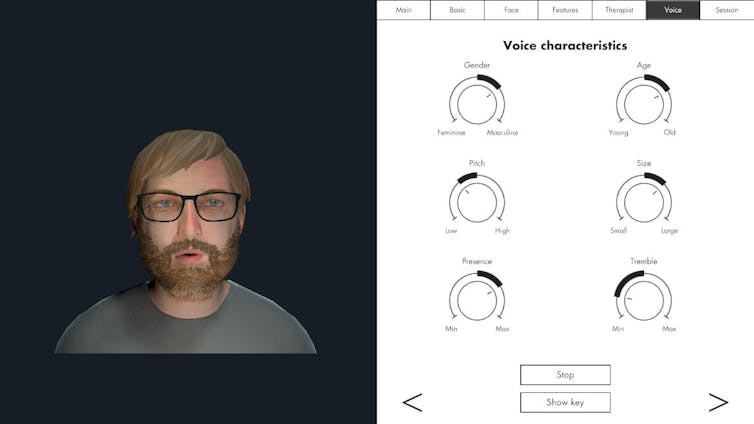

Avatar therapy allows a person to create a virtual representation of the voice or voices, which looks and sounds like what they are experiencing. This can help people regain power in the “relationship” as they interact with the voice character, supported by a therapist.

Jason’s experience

Aged 53, Jason (not his real name) had struggled with persistent voices since his early 20s. Antipsychotic medication had helped him to some extent over the years, but he was still living with distressing voices. Jason tried out avatar therapy as part of a research trial.

He was initially unable to stand up to the voices, but he slowly gained confidence and tested out different ways of responding to the avatar and voices with his therapist’s support.

Jason became more able to set boundaries, such as not listening to them for periods throughout the day. He also felt more able to challenge what they said and make his own choices.

Over a couple of months, Jason started to experience some breaks from the voices each day and his relationship with them started to change. They were no longer like bullies, but more like critical friends pointing out things he could consider or be aware of.

Gaining recognition

Following promising results overseas and its recommendation by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, our team has begun adapting the therapy for an Australian context.

We are trialling delivering avatar therapy from our specialist voices clinic via telehealth. We are also testing whether avatar therapy is more effective than the current standard therapy for hearing voices, based on cognitive behavioural therapy.

As only a minority of people with psychosis receive specialist psychological therapy for hearing voices, we hope our trial will support scaling up these new treatments to be available more routinely across the country.

We would like to acknowledge the advice and input of Dr Nadine Keen (consultant clinical psychologist at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, UK) on this article.

Dr Imogen Bell has received funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council for research mentioned in this article.

Neil Thomas has received funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, the Australian Government Department of Veterans' Affairs and the Wellcome Trust and is a committee member with the Australian Psychological Society.

Dr Rachel Brand has received funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council for research mentioned in this article and is a committee member with the Australian Psychological Society.

Leila Jameel does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.