R.E.M. found themselves at a bit of an impasse in 1992.

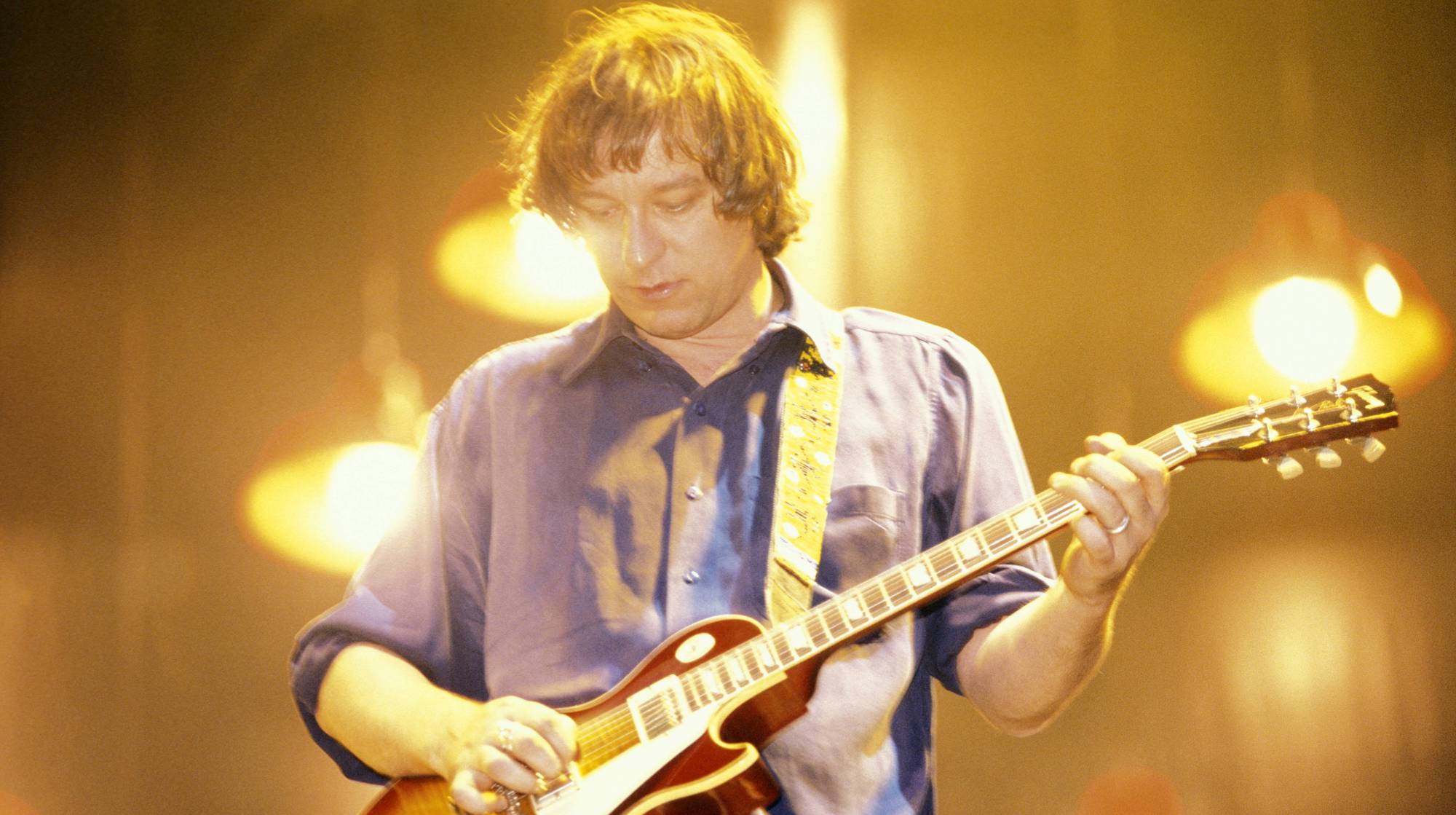

They had vaulted to the top of the nascent independent rock scene in the early 1980s with beguiling songs built on Michael Stipe's Southern Gothic storytelling, Mike Mills' kinetic, melodic bass guitar parts, and Peter Buck's chiming, Byrds-like electric guitar work.

By the late '80s, they'd settled into an ever-so-slightly harder-edged sound, with arena-pleasers like Stand and Orange Crush. From there, in turn, they became superstars in 1991 with Losing My Religion, a mournful smash powered by, of all things, a mandolin.

Looking to retain the experimental drive that inspired Losing My Religion, while ignoring the two-headed pressure to return to their harder-rocking roots and/or produce a hit of Religion's scale, the band created Automatic for the People, a somber, restrained, impeccably-arranged masterpiece that many (this writer included) consider to be the band's creative apex.

Automatic is, as they say, all-killer, no-filler, and has highlights aplenty – among them the evocative, piano-led stunner Nightswimming, the somber and delicate Everybody Hurts, and the swinging Try Not To Breathe. The album's center of gravity, though, is Man on the Moon, Stipe's stirring elegy to the late comedian Andy Kaufman.

The song comes quickly out of the gate with two arresting guitar parts – Peter Buck's star-gazing slide work, and that none-simpler riff: a C, and then a C slid abruptly up two frets, then back down. As Buck explained to Guitar World in 1996, that little slide from C came not from some made-for-Hollywood stroke of inspiration, but a bandmate's fall from a chair.

As the story goes, the stumble happened to R.E.M. drummer Bill Berry, who was idly strumming a C chord.

Asked by GW if the drummer really did basically create the song's verses from the subsequent jerk on the neck, Buck said, “That's literally true.

“He was strumming this C chord and, as he leaned over to get his beer on the amp, he moved his hand, sliding the C up to the third fret,” Buck told Guitar World. “We played that verse forever and, while Michael created this surreal idea of heaven, eventually cobbled together the chorus and bridge.”

As he further explained to GW at the time, Buck's Southern heritage actually made him more reluctant to season the distinctive riff with slide work.

“I overdubbed the slide part in a couple of passes,” he said, adding that, “I grew up in Georgia, so even touching a slide after Duane Allman is almost sacrilegious. I compose almost all my solos – I'd be lost jamming on a I-IV-V.

“Let's just say,” he joked, “I utilized a piece of glass to get some sounds out of the guitar.”