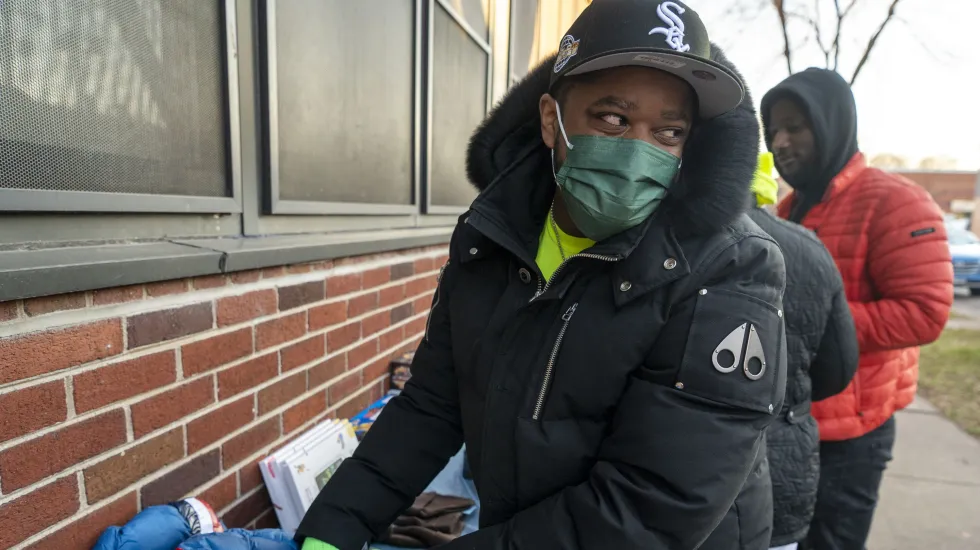

Larice Nelson is about as committed to the principles of nonviolence as anyone you’re likely to meet on the streets of Chicago’s Austin neighborhood.

Walking those streets from his teens until he turned 30, Nelson was arrested an average of twice a year for selling drugs, shooting guns or petty offenses that indicated he was likely getting extra attention from police.

As of 2017, based on a combination of risk factors including his arrest history, his neighborhood and patterns of violence in his social network, Nelson was among the most endangered people in Austin, some 25 times more likely to be shot than a typical Chicagoan. And he was shot twice that year, and seemed destined to become another grim statistic.

But Nelson also had attracted the attention of outreach workers from the Institute for Non-Violence Chicago. After he spent about a year taking part in the institute’s non-violence program, which included mentoring, job training and therapy sessions that helped him overcome a hair-trigger temper, Nelson was hired as a victim advocate.

He now spends his days rushing to crime scenes and hospitals to bring aid — and an introduction to the institute’s curriculum — to shooting victims and their families. The institute’s program is similar to one run by READI Chicago that was the subject of a recent study that demonstrated the combination of therapy and job training can help prevent Chicago’s most at-risk residents from contributing to the city’s violent crime.

But even while he was in the program, avoiding violence wasn’t easy. At the end of an advocacy shift last summer, Nelson stopped near the intersection of West Madison Street and North Central Avenue to chat up some old friends and make a pitch to enroll.

“I was just leaving, and the last thing I said to them was ‘I love you,’” Nelson recalled in a recent interview. “Then ‘pow-pow-pow.’”

Gunfire from a passing car hit Nelson in the arm, back and leg. He spent a few days in the hospital.

Years earlier, he would have rounded up friends to seek violent revenge on the “opps” — the opposition members of rival gangs who might have been the ones who fired the shots.

But Nelson was eager to get back to work. He says now he doesn’t even care to know who shot him.

Nelson’s story illustrates the promise and peril of anti-violence programs that have popped up across Chicago in recent years, and the dilemma facing researchers into anti-violence programs like the Institute for Non-Violence Chicago and its sister organizations.

“You do the program. You do everything right. You change your life,” pointed out Andrew Papachristos, a crime researcher at Northwestern University. “But the opps, they didn’t put down the guns.”

Said Roseanna Ander, executive director of the University of Chicago Crime Lab: “These programs target people that are at incredibly high risk, and even cutting that risk still means some of them are going to be hurt.”