If there’s one attribute shared by truly great artists across the decades it is creative restlessness – the desire and drive to keep moving forward artistically, to break new ground and to set the bar high in terms of your own self-expression and innovation.

Miles Davis, David Bowie, The Beatles, Bjork, Madonna, Prince, Patti Smith and PJ Harvey are among the array of artists who have created music that is ever-shifting, fearless and unique. One key addition to this list is Joni Mitchell, a uniquely gifted singer-songwriter who emerged from the '60s folk circuit and early '70s enclave of Laurel Canyon with more raw talent than most of her male contemporaries combined.

By the time Mitchell launched herself as a solo artist in 1968, she had already established herself as a songwriter of note, penning compositions such as Chelsea Morning and Both Sides Now. Her 1971 masterpiece album Blue set the gold standard for personal and poignant singer-songwriter introspection and her alternative open tunings enhanced her unique sound.

But by 1974’s best-selling album Court And Spark, she was expanding her sonic horizons into jazz, and shifting her vocal range from mezzo-soprano to a deeper and wider contralto. By 1975, her compositions were growing more rhythmically and harmonically complex as she melded elements of jazz, R&B, classical, rock 'n' roll and non-Western beats into her music.

That same year, she began working with revered jazz fusion studio musicians such as Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Pat Metheny and Charles Mingus. Another musician who would become integral to her new sound was a tempestuous bassist from Fort Lauderdale, Florida, called Jaco Pastorius.

As creative couplings go, it wasn’t the most obvious alliance: a folk-based singer-songwriter from laidback Laurel Canyon and a mercurial bassist style rooted in jazz fusion and funk. But Mitchell and Pastorius created a unique shared language. Their diverse melding of styles and sounds would go on to yield some of the finest work of her career.

He looked me in the eye and said, real seriously, ‘Rory, man, I’m the best bass player on earth’. I looked back at him and said, ‘I know’

Pastorius was born in Norristown, Pennsylvania in 1951, but moved with his family to Fort Lauderdale, Florida when he was eight. He started out as a drummer before shifting to double bass then electric bass. Even in his early years his prodigious talent, and ego, shone through. In Bill Milkowski’s 2005 book, Jaco: The Extraordinary and Tragic Life of Jaco Pastorius, his brother Rory recalls an exchange just before Jaco’s 18th birthday. “He looked me in the eye and said, real seriously, ‘Rory, man, I’m the best bass player on earth’. I looked back at him and said, ‘I know’.”

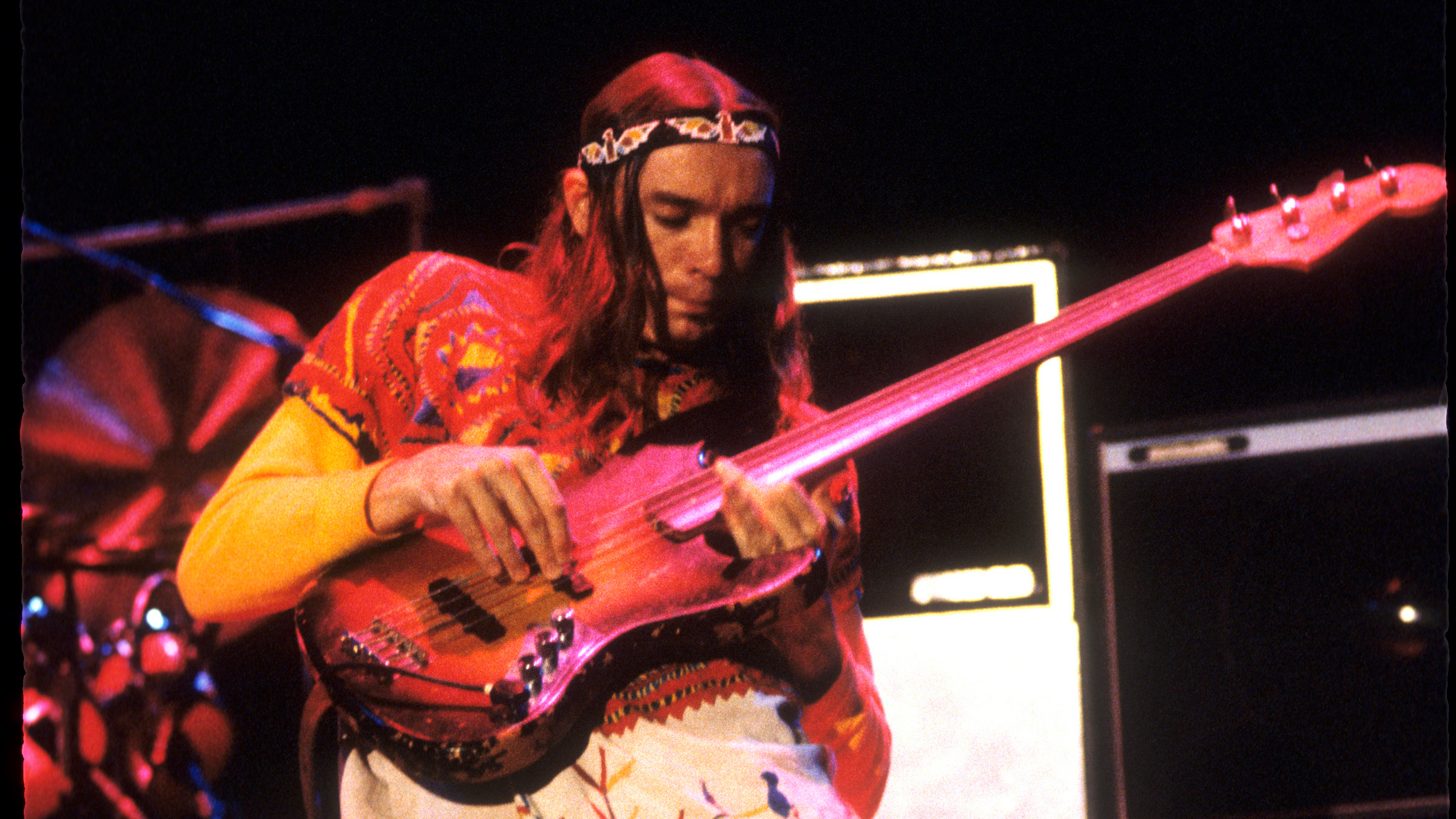

In the early '70s he acquired a 1962 sunburst Fender Jazz Bass. He promptly removed all the frets with a knife, filling in the areas where the frets had been with plastic wood and then coated the fretboard with epoxy. This bass, which became increasingly battered over time, was his primary fretless instrument. He nicknamed it the Bass Of Doom – it's now owned by Metallica's Rob Trujillo but kept by Jaco's son, Felix Pastorius.

Jaco Pastorius went on to teach bass at the University of Miami, where he met guitarist Pat Metheny. In 1976, he recorded his eponymous solo album, drafting in a stellar roster of A-list musicians such as Herbie Hancock, David Sanborn, Wayne Shorter and Sam & Dave.

He became a member of jazz fusion outfit Weather Report from 1976 to 1981 and was heavily influenced by funk, his innovative fretless style utilising harmonics, bass chords and high-end lyrical solos.

There was a time when Jaco and I first worked together when there was nobody I'd rather hang with than him

Pastorius was a mercurial, charismatic figure. But he was also tempestuous and in later years, suffered from drug addiction and mental health problems. He could be incredibly unreliable. But Joni Mitchell was immediately impressed by Pastorius. She also recognised a profound talent when she saw one.

It was early 1976 when Mitchell first encountered him. Mitchell was beginning work on her eighth studio album Hejira, which was inspired by three road trips she had undertaken within the US between late 1975 and early 1976.

In an interview with Musician Magazine in 1987, Mitchell recalled that Pastorius was “arrogant and challenging” but acknowledged that he was also “very alive” and fun to be around.

“The first time he came in, I had never heard him play. I forget who recommended him… There was a time when Jaco and I first worked together when there was nobody I'd rather hang with than him. There was an appreciation, a joie de vivre, a spontaneity.

I had started to think, ‘Why couldn't the bass leave the bottom sometimes and go up and play in the midrange and then return?’

Joni Mitchell

On her two previous albums Court and Spark (1974) and The Hissing Of Summer Lawns (1975), Mitchell had become increasingly dissatisfied with what she called “the dead, distant bass sound” of the 1960s and 1970s. She was also frustrated that most bassists she worked with rarely strayed from the root note of a song.

“I had started to think, ‘Why couldn't the bass leave the bottom sometimes and go up and play in the midrange and then return?’ she said in the December 1987 issue of Musician Magazine. “So when Jaco came in, [percussionist] John Guerin said to me, ‘God, you must love this guy; he almost never plays the root’.”

Mitchell was bowled over by Pastorius’s playing and what it brought to her music. The bassist was steeped in jazz traditions yet taking his sonic clues from artists such as Jimi Hendrix and Tower Of Power. It could easily have overwhelmed Mitchell’s music but it only complemented it. He was a virtuoso on the fretless bass, imbuing his whole character and soul through his music.

Pastorius was also creating new and revelatory sounds on the bass unlike anyone else around. “He had this wide, fat swathe of a sound,” recalled Mitchell in Musician Magazine. “There weren't a lot of gizmos you could put your instrument through then, and the night I got my Roland Jazz Chorus amp, it was sort of a prototype. Jaco and [percussionist] Bobbye Hall and I were playing a benefit up in San Francisco. I tried playing through this thing and Jaco flipped for it. So he stole it off me. He said, ‘Oh yeah, I'm playing through that tonight!’ I said, ‘What are you talking about? This is my new amp!’ He pointed to his rental amp and said, ‘I'm not playing through that piece of shit’. So he took mine!”

I was so thrilled about the way he played. It was exactly what I was waiting for

When Mitchell and the band went on stage that night she was the one plugging into the rented amp while Pastorius gloried in “this huge wonderful busy sound” from the Roland JC. “He was formidable,” recalled Mitchell. “You can hear it in the mixes back then. He was very dominating. But I put up with it; I even got a kick out of it. Because I was so thrilled about the way he played. It was exactly what I was waiting for.”

Pastorius would play bass on four tracks on the Hejira album: Coyote, Hejira, Black Crow and Refuge Of The Roads. There is a sensuality and power to his playing, as is evident on Coyote, where his harmonics, glissando chords and high-end melodies are complemented by moments of impeccable feel, groove and restraint. Despite his ample virtuosity and ego, Pastorius, like all the best players, always served the song.

Pastorius’s presence was equally noticeable on Mitchell’s 1977 album Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, which delved into experimental jazz fusion. On the opening track Overture – Cotton Avenue, there is a synergy between his extraordinary bass lines and Mitchell’s innovative open tunings, while the 16-minute orchestrated jazz fusion freakout that is Paprika Plains is the album’s centrepiece.

The album was panned by some critics and fans for its self-indulgence and lack of cohesion. But its retrospective admirers include Bjork, who according to Pitchfork magazine has cited it as her favourite album and an ongoing source of inspiration.

Another admirer of the album was esteemed jazz composer, bandleader and bassist, Charles Mingus, who had heard Paprika Plains and wanted to collaborate with Mitchell.

After some experimental early sessions, Mitchell settled on a band that included Pastorius, Pat Metheny (guitar), Herbie Hancock (electric piano) and Wayne Shorter (saxophone). Sadly, Mingus died in 1979, before sessions were completed. Mitchell and the band finished the album although it was poorly received by critics and fans.

In August 1979, Joni Mitchell and her band embarked on a six-week tour to promote the album. Recordings from their concert at Santa Barbara County Bowl on 9 September, 1979 were released as the live album Shadows And Light (1980).

This album serves as a stunning record of Pastorius’s contribution to Mitchell’s work, despite its distracting film edits. Pastorius often used an MXR digital delay to layer and loop a chordal figure and would then solo over it. This same looped bass riff technique can be heard at 1:30 on his solo during the concert video for Shadows And Light.

Shadows And Light reached No. 38 in the Billboard 200 chart. Stephen Holden of Rolling Stone called it “a surprise and a triumph” and considered it “one of a handful of great live rock albums”. He also praised Mitchell's backing band as “the finest ensemble that [she] has worked with”.

There’s a real economy of feel to their playing on tracks such as Coyote and Edith And The Kingpin. But this tour would ultimately be the last time Joni Mitchell and Jaco Pastorius would work together.

He went off with Weather Report and they played Japan and I heard tales of him jumping into fountains naked, going amok in the Orient

“There wasn't any real parting point between us,” recalled Mitchell. “We stopped playing together because Jaco didn't play well anymore. Then I lost contact with him. It was more of a drifting apart than a breaking off. He went off with Weather Report and they played Japan and I heard tales of him jumping into fountains naked, going amok in the Orient.”

On 11 September, 1987, after attending a Santana concert in the city of Sunrise, Florida, Pastorius made his way to a club and reportedly kicked in a glass door when he was refused entry. He then got involved in a violent confrontation with a club employee, fell into a coma and was hospitalised. There were encouraging signs that he would recover but he tragically died from a brain haemorrhage on 21 September, 1987, aged 35.

“The day after Jaco died I went back and listened to Mingus,” recalled Mitchell in Musician Magazine. “I went back, basically, to reminisce. And gee, there was some beautiful communication in that playing. I hadn't listened to it for years. The grace of the improvisation on that record… and there were a lot of magic evenings like that.”