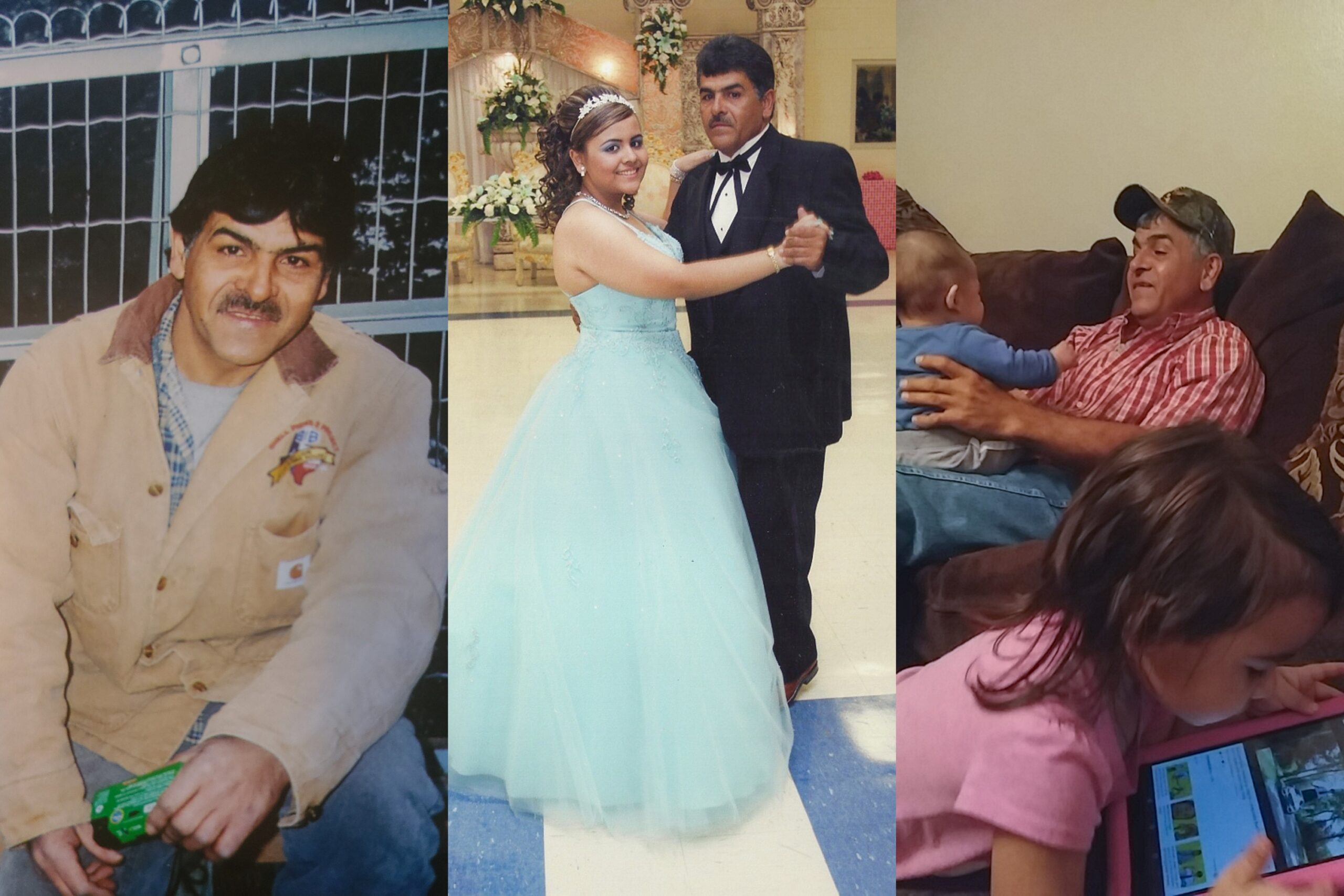

It was mid-afternoon on September 28, 2021, when Antelmo Ramirez began acting strange. A 57-year-old originally from the Mexican state of Nuevo León, Ramirez was working at the sprawling construction site of the Tesla Gigafactory just southeast of Austin, building wooden forms for a concrete pour. He was average height, built sturdy, with short salt-and-pepper hair and stubble to match. According to his oldest daughter, he was a reserved man, though he could be goofy with his grandkids. He’d recently remarried, and his new wife considered him respectful, reliable, and “muy trabajador”—very hardworking.

As captured in archived weather data, the temperature near Ramirez’s worksite hit 96 degrees Fahrenheit that day.

What happened next is recorded in reports by the Travis County Sheriff’s Office, Austin-Travis County Emergency Medical Services (EMS), and the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Sometime after 3 p.m., coworkers noticed that Ramirez—who’d started working for a Tesla contractor named Belcan Services only days before—seemed disoriented. A Belcan supervisor placed Ramirez in an air-conditioned pickup truck for about 10 minutes, according to a sheriff’s deputy’s narrative, but Ramirez remained confused and rambling. The supervisor drove Ramirez about a mile to an on-site medical trailer, where Ramirez displayed “seizure-like activity,” vomited, and became unresponsive.

A Tesla paramedic, per the same deputy’s report, placed the first 911 call shortly before 3:45 p.m., then performed CPR, including delivering a defibrillation shock, until Austin Fire Department and EMS personnel arrived. EMS medics, who would continue CPR for more than an hour, recorded Ramirez’s body temperature variously as 106, 106.4, and 105.1 degrees. They packed him in a body bag filled with ice to try to cool him down, but Ramirez never responded to the resuscitation measures. At 5:02 p.m., he was pronounced dead.

Ramirez’s autopsy report would ultimately identify his cause of death as hyperthermia—the medical term for abnormally high body temperature—which can rapidly overwhelm human cooling mechanisms and effectively cook internal organs in minutes.

Shocking as it seems, on-the-job fatalities like Ramirez’s are somewhat routine in Texas. The state is arguably the nation’s deadliest for workers in general and construction laborers in particular, with heat playing a significant and systemically underrecognized role in work-related illnesses, injuries, and deaths. Despite Texas’ sweltering temperatures, state law doesn’t mandate that employees receive rest breaks. Federal law broadly tasks employers with providing safe workplaces but doesn’t specifically require breaks or other heat precautions. Texas, among the nation’s least-unionized states, also stands alone in letting most private-sector employers opt out of workers’ compensation insurance altogether. The dangers bred by this system of neglect tend to fall heaviest on immigrant and non-white men.

Tesla, Elon Musk’s electric vehicle company, stormed into employer-friendly Texas in 2020 with plans both to build its newest Gigafactory and relocate its headquarters to the Travis County site, nestled in a sweeping bend of the Colorado River a few miles from Austin’s airport. Behind the corporation trailed a long history of worker safety violations, along with allegations of underreporting injuries to regulators, in California and Nevada. Central Texas labor advocates sounded the alarm, and county government extracted some safety promises in return for tax breaks. But Ramirez’s case, which the Texas Observer has spent five months investigating, not only exposes the state’s shredded safety net for manual laborers but also reveals that Tesla failed to comprehensively report accidents in compliance filings required by the county.

At 6:34 p.m., Jessica Galea, an investigator for the Travis County Medical Examiner’s Office, arrived at the Tesla site. In the medical trailer, she saw Ramirez’s body still in the ice-filled bag, his eyes bloodshot, clothed only in gray socks, according to her written report. A foreman then led her the mile back to Ramirez’s jobsite, “off the roadway down a slope,” where she observed two barrels full of ice and bottled water. “There were no sources of shade,” she noted, and the foreman “could not specify when or how long their breaks were.” Ultimately, Ramirez was placed into a blue body bag for transport. After photographing the scene, Galea departed at about 7:30 p.m.

According to court filings in Starr County, where Ramirez lived when not traveling for work, he died without a will, his estate consisting almost entirely of a Chevrolet pickup “worth approximately $25,000.”

In an initial autopsy report, signed in December 2021, the Travis County medical examiner identified Ramirez’s cause of death as “hypertensive and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” meaning high blood pressure and plaque buildup in the arteries. Only later did the examiner’s office receive EMS’ temperature recordings, a county spokesperson said, and amend its findings. In a second report, signed March 3, 2022, the examiner changed the cause of death to hyperthermia—which “can cause fatal abnormal heart beats (arrhythmia), seizures, coma, and death”—while downgrading blood pressure and plaque to a “contributing condition.”

On March 4 of last year, OSHA—the federal agency charged with investigating worker fatalities—issued a citation stemming from Ramirez’s death that alleged Belcan Services, his employer, had exposed workers “to the recognized hazard of high ambient heat with a heat index of 98°F in direct sun.” The fine was for only $14,502, the maximum penalty for a single “serious” violation, less than half the cost of Tesla’s cheapest new car. Belcan contested the citation, and a trial is currently scheduled for July before an administrative law judge.

OSHA, a small and chronically understaffed agency, has struggled to make heat-related citations stick due to a lack of regulatory clarity on the matter and successful employer challenges. In recent years, fines for heat exposure cases in Ohio and Texas have been thrown out—just one of many barriers, advocates say, that shield employers from accountability for the lives of workers like Ramirez.

From the agricultural fields of California to warehouses in Pennsylvania to oil-and-gas plays in the upper Midwest, workers across America risk their lives for wages, with the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) recording some 5,000 on-the-job deaths annually. Of all 50 states, however, Texas stands out as something of a killing field for the laborers who fuel its always-hot economy.

In 2021, a worker in the Lone Star State died on the job every 16.5 hours, and a construction laborer perished every 3 days, according to BLS data. An Observer analysis further revealed that, every year from 2009 to 2021, Texas saw more worker deaths than any other state, including more-populous California, while recording the highest worker death rate among the nation’s five largest states. From 2011 to 2021, Texas saw 1,306 total deaths of construction workers, more than California and Pennsylvania combined.

“Texas is just a really terrible place for construction workers to do their job,” said David Chincanchan, policy director for the Workers Defense Project, a nonprofit that organizes Texas construction laborers. “We are nowhere near where some other places in the nation are in terms of worker protections.”

Dangers abound on construction sites. The federal fatality data identify “falls, slips, and trips” and “transportation incidents” as among the most common accident types. According to BLS, deaths from “exposure to environmental heat” are rare: just a few dozen annually across all industries nationwide. But advocates and federal agencies argue the BLS statistics specifically fail to capture heat deaths like that of Antelmo Ramirez.

“We’re definitely well aware of Tesla’s history of apparent negligence towards their workers.”

Here’s how heat kills: When you do physical work, your body is exposed both to internal metabolic heat and external environmental heat. To cool off, you increase blood circulation and sweat. But with prolonged heat exposure and as dehydration sets in, these cooling mechanisms can fail, leading to an escalating series of symptoms including dizziness, nausea, and kidney damage. In the worst cases, heat stroke occurs; internal temperature can rise to 106 degrees within minutes, causing confusion, seizures, and death.

Heat-related work deaths often go unrecognized due to weaknesses of both data collection and death investigation. For example, an overheated worker who becomes dizzy and collapses might simply be recorded as a falling death. And medical examiners generally need specific circumstantial evidence (like EMS body temperature readings) to diagnose death by hyperthermia. As the federal Environmental Protection Agency wrote in a recent report: “In many cases, the medical examiner might classify the cause of death as a cardiovascular or respiratory disease, not knowing for certain whether heat was a contributing factor.”

In a 2022 report, the nonprofit advocacy group Public Citizen used a combination of BLS data, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) statistics, California workers’ compensation claims figures, and academic studies to estimate that heat causes 170,000 work-related injuries and between 600 and 2,000 deaths annually.

For those who survive, heat stroke can leave permanent organ damage, cognitive impairment, and increased vulnerability to heat. It’s complicated to determine exactly what ambient temperature is dangerous to workers, but in 2018 the CDC suggested that 85 degrees “could be used as a screening threshold to prevent heat-related illness.” Safety experts and OSHA stress that heat-related injury is entirely avoidable, largely through three simple measures: plenty of cold water, regular rest breaks, and time in shade. But many employers forgo these precautions in the absence of effective regulation and in pursuit of profit.

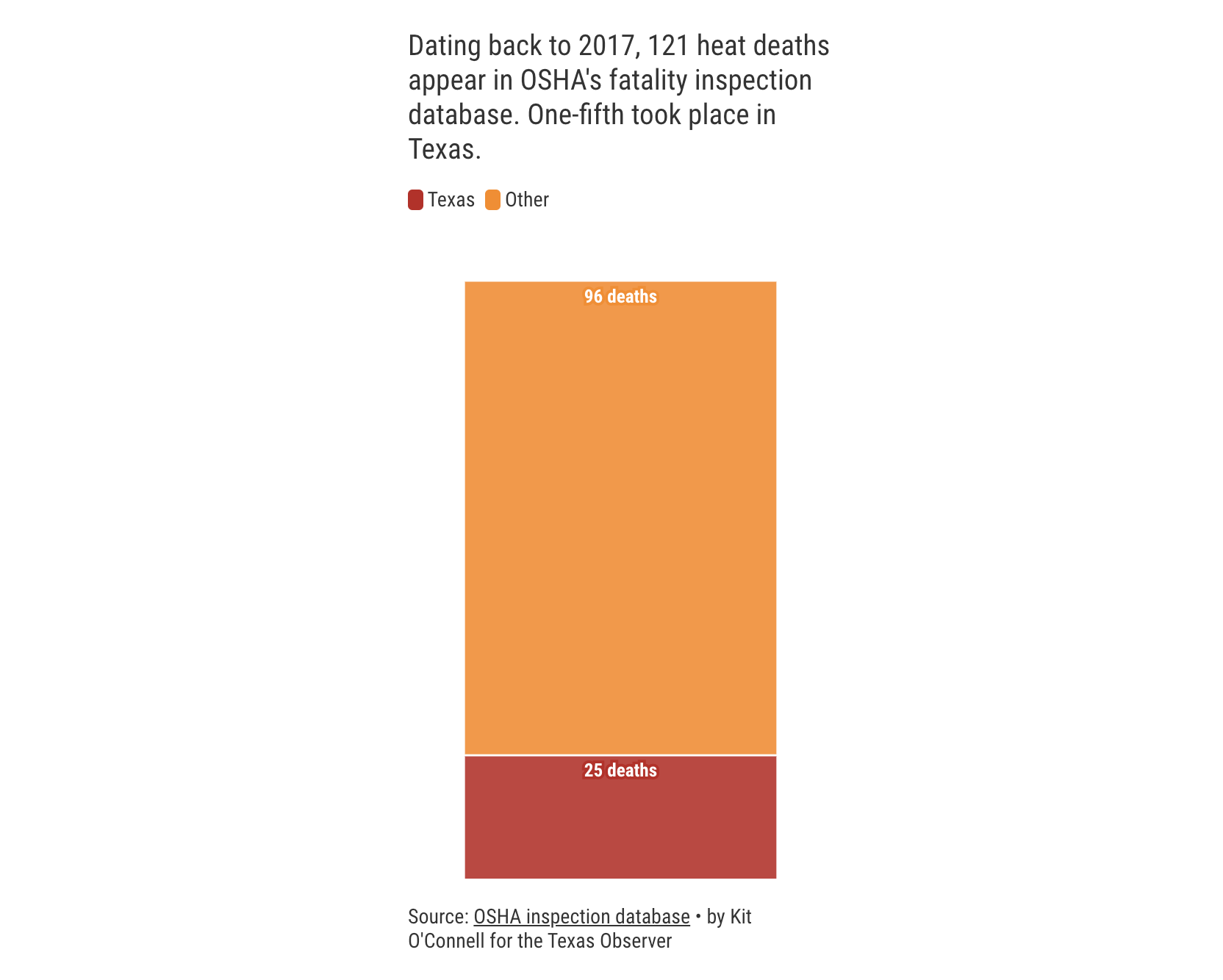

Due to employer underreporting and limited jurisdiction, OSHA only investigates around a fifth as many worker fatalities as BLS reports annually. A keyword search for “heat” in OSHA’s fatality inspection database produces just about 120 heat-related investigations since 2017, with 25 in Texas.

Since 1972, a federal research agency called the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has recommended that OSHA adopt a federal heat safety standard—an enforceable set of rules such as those that exist for fall protection and asbestos exposure. Yet OSHA still hasn’t done so.

“We’ve known about the hazards of heat pretty much as long as we’ve known about work,” said Jordan Barab, a former OSHA deputy assistant secretary under President Barack Obama. “Although it’s a very old health issue, it’s still unfortunately a relatively new regulatory issue, at least on the federal level.”

A few states have stepped into the regulatory breach with their own heat standards. These include California, Washington, Oregon, and Minnesota—states with cooler average temperatures than Texas. Per Public Citizen, California’s standard may have cut heat injuries by 30 percent since its implementation in 2005. Texas has taken no such action. Two Texas cities, Austin and Dallas, have passed their own rest break policies for construction workers, but the GOP-run state Legislature has repeatedly tried to kill these local laws and may succeed this year. (The Tesla site in Travis County is outside Austin city limits, so the municipal rest break policy doesn’t apply there.)

In lieu of a federal heat standard, OSHA has relied on education campaigns encouraging employers to protect their workers, plus some proactive site visits during hot months to encourage best practices. For any heat-related enforcement, the agency has depended on a 50-year-old catch-all bit of statute called the General Duty Clause—as it did in Ramirez’s case—which states broadly that employers must provide workplaces free of “recognized hazards.” When challenged by employers, OSHA has run into trouble defending these citations partly because the agency itself has declined to issue a clear heat standard. In 2019, a federal review commission tossed a heat fatality case against a roofing company and, citing that ruling, an administrative law judge in 2020 overturned five fines for heat illnesses among U.S. Postal Service workers.

“It’s a slow slog to do General Duty Clause citations,” said Barab. “Not only do they get challenged and they get overturned, but it’s just a lot more work.”

In 2021, the Biden administration did finally start the regulatory process of enacting a federal OSHA heat standard, but the process could take five years or more and might be interrupted should a Republican take the presidency in 2025. In its notice of proposed rulemaking, OSHA specified that while most heat fatalities occur outdoors, some do occur indoors. The agency identified agriculture and construction as among the most vulnerable industries, with climate change set to make these jobs evermore dangerous.

One-third of workers killed by heat since 2010 were Hispanic, OSHA said, while Public Citizen stated that low-income workers suffered five times the heat injuries of better-paid laborers. In Texas, the Observer found that from 2011 to 2018, foreign-born Hispanics (overwhelmingly men)—who form the backbone of the state’s construction industry—made up 21 percent of total worker deaths while constituting just 11 percent of the population.

OSHA also said in its notice that “70% of [heat] deaths occur within the first few days of work”—as was the case with Ramirez—underscoring the importance of “acclimatizing” new employees by slowly ramping up their duties.

In almost every respect, then, Ramirez’s case was archetypal. He was a Mexico-born man, working construction in high temperatures, in Texas, with no legal right to rest breaks, who was new on the job. All that, along with one other typical feature: As with each of us who goes to work, some loved one somewhere was expecting him to get home safe that day.

Jasmin Muñoz, then 29, only hazily recalls the moment she learned she’d lost her father. “I remember I was standing in my living room at that point and my legs went numb—my husband was behind me—and I guess I just kind of fell to the floor,” she said. “I didn’t even realize my kids were [there]; I don’t know if I screamed.”

A public school teacher in the Houston suburb of Pasadena, Muñoz got the news from an aunt, part of a series of chaotic family phone calls that occurred the Tuesday afternoon and evening that Antelmo Ramirez died. Her aunt’s words—“tu papá falleció [your dad passed away]”—were hard to believe. Why would her father, who’d just been fine, be dead now of an apparent heart attack at work?

Two days prior, Muñoz had been in Illinois for an in-law’s wedding, but she’d talked to Ramirez by phone that evening. It was one of those special family calls where you end up talking longer than expected. She made plans to call again the next day, Monday, but she and her husband and two kids got back late to Houston. No problem, she figured, she could just call him Tuesday after he got off work—a chance she’d never get.

Shock blurred those early days. A cousin came to take the kids, then 3 and 5 years old. Come Wednesday, she found herself at school making copies for a substitute. (“Looking back, I don’t know what I was doing at school,” she said.) And, soon, she was at the funeral in Starr County, where her dad’s family had gotten their start in America.

Antelmo Ramirez was originally from the tiny town of Agualeguas, about 30 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border. In his teens, Muñoz said, her father migrated to the Roma area in the rural Texas border county of Starr. Ramirez was a migrant farmworker alongside other family members, following the onion and melon harvests, traveling seasonally to Illinois to work the cornfields, eventually marrying Muñoz’s mother and becoming a U.S. citizen in the ’90s. Muñoz and her two younger siblings were raised in both the Houston area and Starr County, she said, as Ramirez transitioned from farmwork to working at refineries, specializing in scaffold-building. She and her “apá” were always tight: “I was like his little shadow once he came home from work,” she said.

During Muñoz’s childhood, Ramirez was often gone long stretches for refinery gigs. She recalls that, one of the first times he said goodbye before leaving for a job, “I just thought that he was going to leave us forever; I was bawling.” So after that, to avoid the scene, he would often leave “like at four in the morning.”

She and Ramirez bonded over similar personalities. She described him variously as shy, generous, frank, and a bit particular. She recalls him giving her grief as an adult for using the wrong brand of floor cleaner, and he was health-conscious, always reminding her that “es mejor comer en casa, like, it’s better to eat at home.”

In his final years, Ramirez—who separated from his kids’ mom while Muñoz was in college—was embracing his role as grandfather. When Muñoz, then living in Illinois, had her first child, Ramirez drove all the way up from Texas with a cooler full of fajita meat. She tried telling him there were Mexican stores up north too, but he insisted it wouldn’t be the same. Since Muñoz didn’t have a grill, he went out and bought one for the cookout. At her second birth, now back in the Houston area, he came to the hospital but lasted only briefly in the delivery room: “He couldn’t handle seeing me in pain.”

As her children grew, Muñoz watched a silly side of Ramirez reemerge that she hadn’t seen since she was little. He didn’t like being photographed, but she would sneak photos of him playing with her kids.

After the funeral, Muñoz finally told her son and daughter what had happened, summoning the child-friendly phrases we use in situations like these. “God sometimes needs more angels, and your grandpa had a big heart so your grandpa’s heart just stopped,” she recalls saying. Not long ago, her now-5-year-old son said he was waiting for a shooting star so he could wish for her dad’s return. “I guess it broke me,” she said, “but what broke me more was that he didn’t say ‘my grandpa.’ He said ‘your dad.’”

Reminders are ever-present. There’s the violin that he helped buy her when she was a teenage mariachi, an instrument she can’t bring herself to play much anymore. Plus, the Tuesday that he died had been school picture day. “So I see the picture that was taken of me and my kids that day, and it’s like a sense of security was stolen from us,” Muñoz said, “because we know that it was not his time.”

A year prior to his death, Ramirez had also remarried. Reached by phone, his wife Mirtha Prado Franco said she was still living with Ramirez’s mother in Starr County and that his passing had left her in a kind of limbo. “I don’t have anything,” she said. “I’m just up in the air.”

In May 2020, Tesla—an electric car behemoth currently worth some $500 billion—announced that Austin and Tulsa, Oklahoma, were finalists for the corporation’s 5th “Gigafactory,” the company’s grandiose term for its production facilities.

Corporations like Tesla and Amazon use competition between cities to squeeze out maximal tax breaks, even though critics say incentives rarely sway firms’ location decisions. As multiple layers of government in the Austin area began debating tax deals, labor and good-government advocates balked. For one, Tesla’s CEO Elon Musk had announced possible plans that same month to relocate the company’s headquarters to Texas in protest of California COVID-19 restrictions, just two months into the deadly pandemic. For another, Tesla’s history of worker safety issues was already well-established.

Between 2018 and 2020, news outlets including Reveal, Bloomberg, and USA Today found that Tesla repeatedly misclassified and underreported injuries to regulators at its California and Nevada factories. And from 2018 through March 2023, Tesla was cited by OSHA 49 times for 116 total safety violations—twice as many citations as Ford and General Motors combined for three times as many violations—according to an Observer analysis of federal data. In July 2019, a 61-year-old was found dead early one morning at Tesla’s Nevada Gigafactory, though the local medical examiner’s office told the Observer the death was caused naturally by hypertension and plaque.

“There’s a long history of citations by OSHA, far more than other companies,” said Marcy Goldstein-Gelb, co-executive director of the nonprofit National Council for Occupational Safety and Health. “We’re definitely well aware of Tesla’s history of apparent negligence towards their workers.”

Despite these concerns, the Del Valle Independent School District, which serves an unincorporated and poor area southeast of Austin proper, voted 7-1 in July 2020 to grant Tesla a property tax break worth some $50 million. One trustee called the process “completely rushed.”

Hot on the school district’s heels, Travis County—which lifted a self-imposed moratorium on economic incentives just to consider Tesla’s proposal—took up its own tax proposal. Some labor and community activists urged delay, arguing Tesla was coming to Austin regardless of the deal, while one county commissioner “plead[ed] for a little bit of time” to get more information. Commissioners passed the agreement anyway on July 14, with four “yes” votes and one abstention.

The county’s Tesla deal pledged at least $14 million in property tax rebates over 10 years. In return, Tesla promised to create 5,000 new full-time jobs, which the county said would help residents weather the COVID-induced recession. Even with the rebates, the county said it would take in far more tax revenue from Tesla than it did from the sand and gravel mine that operated on the company’s desired 2,100-acre site. The deal also included some labor-friendly terms such as a $15 hourly wage floor, but labor advocates including Workers Defense Project criticized it for lacking independent compliance monitoring—which Workers Defense said amounted to letting Tesla “police themselves.” About a week after the county voted, Musk revealed Austin had beat out Tulsa for the factory, and initial construction reportedly began that month.

Soon, Workers Defense started receiving reports from laborers of unsafe conditions and injuries at the site. Last November, the organization filed complaints with the federal Labor Department alleging that an unspecified number of workers, employed by Tesla contractors, had wages stolen during Gigafactory construction and that a worker was provided with falsified OSHA safety training certificates. The outlet More Perfect Union also reported on workers who fainted from heat and sustained a serious hand injury at the site, while an Observer review of OSHA inspections revealed workers who were exposed to high carbon monoxide levels and one who fractured an arm.

Per its agreement with Travis County, Tesla must report to the county “the number of injuries and deaths, if any, that may have occurred in the performance of the construction” of the factory. In Tesla’s report covering 2021, obtained from the county by the Observer, the company provided a single OSHA Form 300 injury log, which lists 21 work-related injuries or illnesses including a sprained hand, lacerated mouth, and broken elbow.

Tesla’s report to Travis County, however, did not include all injuries or fatalities that took place during site construction. For example, it didn’t include Antelmo Ramirez’s death from September 2021. And Hannah Alexander, a Workers Defense Project staff attorney, told the Observer she’s spoken with multiple other workers hurt at the Tesla site in 2021 “whose injuries are not reported.”

“I want to be able to look at my kids and tell them I did what I could to get answers and prevent this horrible thing that happened to your grandpa from happening ever again.”

Based on the document Tesla provided, the company appears to have reported only injuries to its own employees and not those of its contractors and subcontractors. The feds don’t publish comprehensive injury data for specific worksites, which can host many separate long- and short-term employers, but OSHA does publish some aggregate injury log data. Using the Texas Gigafactory address, the Observer identified at least six additional injuries in OSHA’s 2021 data that Tesla did not report to Travis County, in addition to Ramirez’s death.

These omissions came despite Tesla’s own insurance manual, as submitted to the county, stating: “All injuries, no matter how small, shall be reported to Tesla and Contractor(s) immediately.”

The Observer first asked Travis County about the injury discrepancy in March. Around the end of that month, Tesla submitted its latest annual report to the county covering 2022, which the Observer also obtained from the county. This time, Tesla again included an OSHA injury log—listing 100 injuries, most frequently to employees with the common Tesla title of “production associate”—but for the first time Tesla also submitted an additional document, which the county provided the Observer as a PDF labeled “2022 Contractor Event List.” The new document listed 52 more injuries to employees of apparent Tesla contractors. Of those 52 injuries, 25 were to employees of Belcan, the company that employed Antelmo Ramirez in 2021.

In early April, Travis County told the Observer it was asking Tesla to provide additional injury information for years prior to 2022. The county also said it had not actually issued any property tax rebates to Tesla yet, as it continues to review compliance.

“Travis County remains committed to protecting workers’ rights and improving working conditions for those who are building our community,” said spokesperson Hector Nieto in a written statement. “This is why the Travis County Commissioners Court includes requirements in its Economic Development Incentive Agreements. … Staff will assess whether any of the requirements were not met, how to best rectify the noncompliance and provide recommendations to the Commissioners Court for further action.”

The 10-million-square-foot Texas Gigafactory officially opened last April with a “cyber rodeo” party—featuring fireworks and Elon Musk in a cowboy hat—which prompted the school district to send kids home early that day to dodge traffic. This April, the factory hit a production milestone of 4,000 Model Y vehicles in a week. Tesla is still building out its site, as reported in January by the Austin American-Statesman, planning more than $700 million in additional construction.

The Travis County-Tesla agreement also specified that Tesla would “use its best efforts to submit a successful application” for OSHA’s Voluntary Protection Program, which substitutes proactive compliance and cooperation for periodic inspections. In April, an OSHA spokesperson told the Observer the company had not applied.

Tesla, which dissolved its public relations team in 2020, did not respond to numerous messages to its press email account and emails or calls to five senior employees and its board chair.

Jasmin Muñoz had a dream in late 2021. Her father and grandfather, also deceased, were talking. Her dad turned to her and said, mysteriously, that she was going to receive a phone call and he needed her to be strong. After that, her suspicions about Ramirez’s death grew.

In March 2022, when she learned the medical examiner changed his cause of death to hyperthermia, she knew her dad’s death had been more than an accident—it had been an injustice. She found an attorney, who filed a lawsuit in Harris County last May on behalf of Muñoz and her siblings against Belcan Services Group L.P. and Tesla, Inc.

The suit alleges the companies failed to properly train employees, to furnish a safe workplace, and to provide medical treatment. Specifically, the complaint accuses the companies of gross negligence, defined under state law as a “conscious indifference” to known dangers. In Texas, this bar must be cleared in order to sue employers who carried workers’ compensation insurance, which Belcan and Tesla did.

In March of this year, Muñoz told the Observer that in her phone call with her dad two days before he died, Ramirez mentioned that “he felt like he couldn’t take a break” at the Tesla site. Prado Franco, Ramirez’s wife, told the Observer she believed there wasn’t shade and that the site was generally “descuidado,” messy or neglected.

From sheriff and fire department reports, the Observer obtained contact information for six people who were at the jobsite that day. Reached by phone, two of the six gave brief comments. Gaspar Cano, identified as a foreman in the sheriff’s report and as the person who drove Ramirez from the worksite to the medical trailer, said “none whatsoever” when asked if there were safety issues. Cano stated there were sufficient breaks and water before hanging up.

Felipe Benavides, also identified as a foreman in the report, said: “Everything was good safety-wise. … There was ice water, breaks; since [Ramirez] was fresh to the job he was the least-tasked person,” adding that Ramirez had unspecified “medical issues.”

The Observer was unable to obtain the 911 call from that day—as Austin-Travis County EMS advised it had been deleted—and is still awaiting release of Travis County sheriff’s department dashcam videos.

In court filings, Belcan and Tesla both denied wrongdoing and attributed Ramirez’s death to “pre-existing medical conditions.” Tesla further blamed Ramirez for failing to “exercise ordinary care.” Muñoz and Prado Franco both told the Observer they were unaware of any medical conditions that might have triggered Ramirez’s death. The medical examiner said Ramirez had “no known medical history.”

Tesla also claimed, in its filing, to not be liable because Ramirez worked for a contractor. Goldstein-Gelb, the worker safety expert with the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health, told the Observer there is legal precedent for a company in Tesla’s position being responsible for what happens on its site, pointing to a particular settlement paid by Walmart in 2013 in Massachusetts.

Trials in the Harris County lawsuit and the contested OSHA citation case are pending. In response to Observer requests for comment, a Belcan spokesperson said the company “does not comment on pending legal matters.”

Meanwhile, Muñoz is left to chart her own path to closure. To get there, she wants more information about what happened to her dad, and she wants to spread the word about worker safety so that others won’t suffer the same fate. “I want to not be stuck in September 2021,” she said, “and I want to be able to look at my kids and tell them I did what I could to get answers and prevent this horrible thing that happened to your grandpa from happening ever again.”

Muñoz also wants her father to be remembered for his perseverance and generosity—for his story of going from migrant farmworker to parent of kids with professional careers: two teachers and a physician assistant. In their dad’s honor, the siblings have started a scholarship at Roma High School for students who work the fields like he once did.

“Technically, he’s considered a victim, but he was such a strong person that his name shouldn’t be like, ‘Oh, he’s just a victim,’” Muñoz said. “He represented so much, and he represented the American Dream.”

Editor’s Note: The writer’s spouse, who was not involved in the production of this story, is employed by the Workers Defense Project.