Chicago’s murder total last year surged to levels not seen in a quarter-century, but embattled police Supt. David Brown has frequently noted a positive data point amid the spike in violence: His department “cleared” more murder cases in 2021 than in any other year in nearly two decades.

The statistic on cases cleared is usually among the list of figures Brown cites in public remarks, alongside record numbers of handguns seized by officers and rising arrest totals for carjackings.

CPD detectives “cleared over 400 homicides in 2021,” Brown said at a January press conference, one of several times he’s mentioned the figure in public remarks. “That’t the most cleared in 19 years.”

Indeed, Chicago police closed exactly 400 murder cases in 2021, well above the average solved during each of the last several years, according to statistics provided in response to a public records request. That’s nearly 50 more cases closed than in 2020 and well above the average of 250 in each of the five years prior to that.

Based on the department’s official total of 797 murders in 2021, that amounted to a “clearance rate” of better than 50% last year.

But an analysis by the Sun-Times found that higher rate doesn’t mean many more people are being brought to justice than in years past.

In fact, a closer look at CPD’s clearance rate reveals that half of those cases — 199 — were closed “exceptionally,” meaning that no suspect was charged. Under CPD policy, detectives are allowed to clear a case when the suspect is dead, prosecutors refuse to make a charge or police believe they know who did it but nevertheless don’t make an arrest.

What’s more, one of every seven cases taken off CPD’s books last year was actually committed more than 10 years ago, including one that happened a half-century ago, which CPD attributed to providing extra resources to the department’s Cold Case team. Since those cases were officially cleared in 2021, they are counted against the 797 murder total, further improving last year’s clearance rate even though they happened years before.

When all is said and done, the department actually made arrests in fewer cases than in 2020, when 209 people were charged, figures show.

Despite Brown’s boasts, CPD’s efforts to boost clearance rates without an arrest or charges could be detrimental to crime fighting efforts in the long run, experts said.

Both residents and police officers in violence-plagued communities want to see killers taken off the streets, and a clearance stats that are padded by closing decades-old cases or stalled by reluctant prosecutors does little to build confidence in the community or boost police morale, said Christopher Herrmann, a researcher at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York who has studied clearance data.

“It’s really kind of a negative, downward spiral,” Herrmann said. “When a community doesn’t see murders getting solved, they’re less likely to help the police, because what good does it do, right? [Police] never solve anything, anyway. And when the police see that the community isn’t stepping up to help, they’re going to question how much energy and brainpower do they want to put into a case.”

‘The person that did this to my son is still out there’

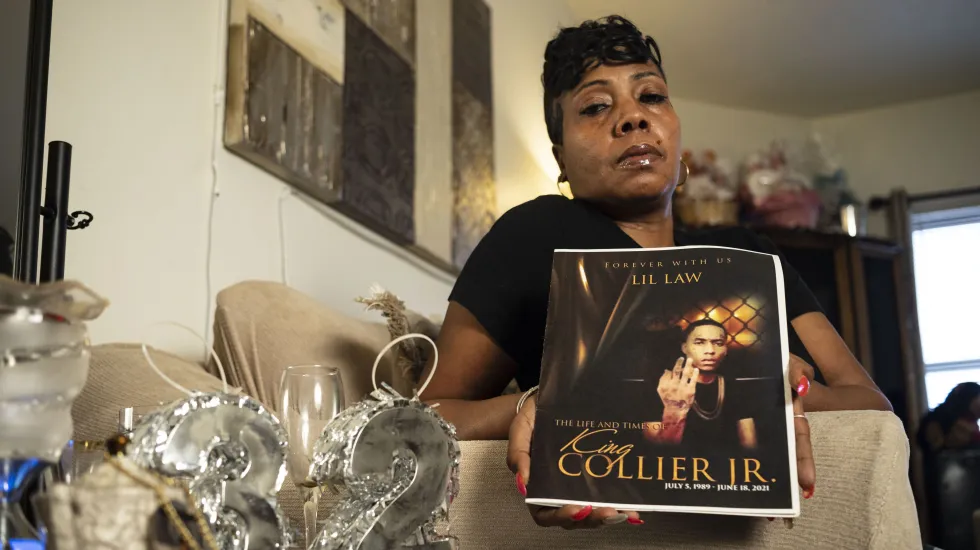

Caught in that spiral is Erica Collier, whose 31-year-old son, King, was one of the 836 people killed inside Chicago city limits in 2021 (the larger figure includes homicides cops deemed justifiable or that took place on expressways, which are investigated by the Illinois State Police so are not included in CPD’s calculations).

King Collier, an aspiring musician and artist who did demolition work to pay his bills, was shot in broad daylight on a June afternoon outside the entrance to the Parkway Gardens housing project in Woodlawn.

“I heard people screaming, so I know people were out there. Someone saw something,” Erica Collier said in an interview this week. But no one seems to have come forward to police, who have been slow to provide Collier updates her son’s case. Collier said she informed investigators that social media chatter indicated her son was mistaken for a gang member in the neighborhood, but they weren’t impressed with the lead.

“The detective told me once that they would just have to wait for the gun to be used in another shooting so they could connect it,” Collier said.

“I’m living every day, knowing the person that did this to my son is still out there, and you’re telling me I got to wait for someone else to get hurt before they can find him? That don’t seem right to me.”

Decades-old case closures add to 2021 clearance rate

CPD uses the same formula that the FBI has used for years to calculate the department’s clearance rate: dividing the number of cases solved — no matter what year the murder took place — by the number of murders in a given year.

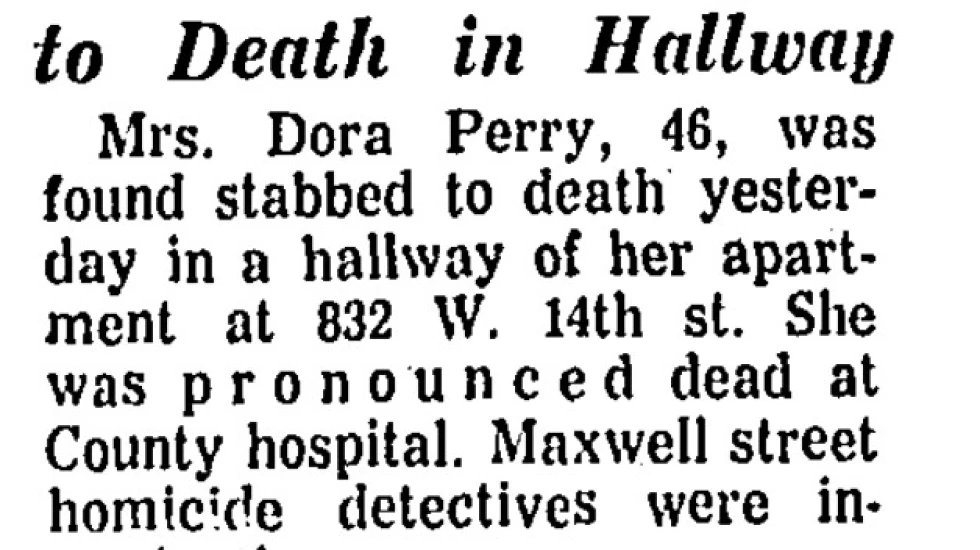

But using that standard means CPD’s 50% clearance rate for 2021 includes solving the murder of Dora Perry in Little Italy. Perry’s case was marked closed last September — more than 52 years after Perry was killed in August of 1968.

Perry’s was one of 56 murders that was on CPD’s books for more than 10 years before being cleared last year. Fourteen were 30 or more years old.

Clearance rates from 2015 to 2021

| Clearance Rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Murders | Same Year | All | |

No one was charged in any of those old murders, CPD records show: in 30 of the cases, prosecutors declined to file charges against suspects identified by police, and in the rest, the alleged killer had already died.

Tamar Mannasah, founder of Mothers Against Senseless Killings, doesn’t give police much credit for solving cases after dozens of years. Solving cases within weeks or months gives comfort to victims’ families and can prevent revenge shootings

“It’s almost an insult, she said, adding “like you’re doing it to look good. People don’t retaliate when somebody goes to jail. And if you have to see the person who murdered your loved one out walking around, that will put you in a murderous rage yourself.”

Prosecutors deny charges in record number of cases

Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx’s office’s decision to reject charges in those older cases contributed to what is likely a record number of murder cases turned down by prosecutors.

Foxx’s office refused to bring charges in 131 cases detectives marked cleared — the most cases denied by the office in the six years that Foxx has been the county’s top prosecutor.

In public statements and off-the-record complaints, police and Mayor Lori Lightfoot have claimed prosecutors are turning down solid cases brought to them by detectives.

Foxx has defended charging decisions by her office, pointing to state laws that have raised the bar for evidence in murder cases. And a report by her office notes that under the data it maintains, it has brought charges in three-quarters of cases police brought to them — even though its figures show CPD made arrests in just 26% of the homicides that occurred in 2021.

“If the totality of evidence is enough to approve charges, then we do,” spokeswoman Cristina Villarreal said in an email. “If there is not enough evidence to meet our burden of proof in court, we work closely with law enforcement to guide them in what evidence would help us meet the burden in court.”

Though no one will face justice in those crimes, police say they are done actively investigating unless new evidence appears, and they are now considered “clear-closed” by the department.

Percentage of cleared murder cases ending in approved charges

Asked about why there were so many cases closed without an arrest during a year when Chicago saw near-record numbers of homicides, spokesman Don Terry said that department tabulates case clearances according to FBI guidelines.

Although the FBI allows it, many other police departments don’t include cases where prosecutors have refused charges when calculating their clearance rates, said Charles Wellford, a criminologist and emeritus professor at University of Maryland-College Park.

“That level of exceptional clearances in Chicago is unusual,” Wellford said.

Few detectives chasing many murders

CPD has made efforts to revamp its detective bureau under Chief Brendan Deenihan, who took the job in 2020, a year after a national policing agency issued a lengthy report outlining shortcomings in CPD’s investigations.

Among other points, a 2019 review from the Police Executive Research Forum noted that among nearly 12,000 officers, CPD had only 138 detectives handling homicides, as part of a unit that also investigated gang and sex crimes. Some detectives said they were saddled with more than 10 cases.

The department now has 180 detectives working murder investigations, meaning each was given an average of 4.4 new cases to solve last year. Terry said the department plans to add more to bring the recommended case load down to three to four new cases per detective, Terry said.

The sheer number of murders Chicago makes the job of solving murders more difficult than in other cities, said Herrmann, the John Jay researcher. The city sees more killings than New York and Los Angeles combined, and both cities have more detectives chasing far fewer cases.

As of 2019, 11% of New York’s sworn officers and nearly 15% of L.A.’s cops are detectives, compared to 8.4% here.

“Chicago detectives are definitely respected, but everyone acknowledges that they have so much more work to do,” Herrmann said.

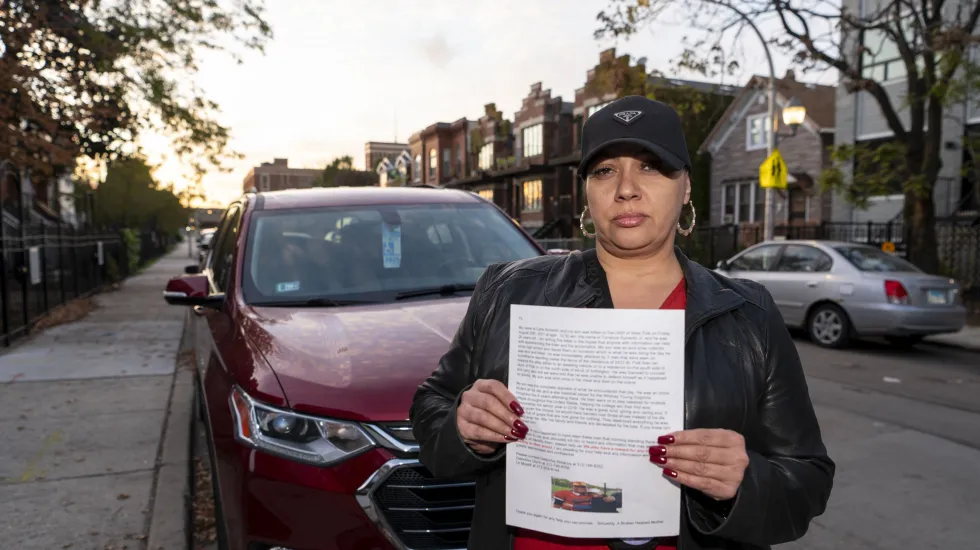

Police also get positive reviews from Carla Sumerlin, whose son, Torrance, was shot dead in the Tri-Taylor neighborhood in August. Earlier this month, two men were charged in the slaying, clearing his case off CPD’s books a little over six months after it happened.

Carla Sumerlin stayed in constant contact with police, and did some detective work herself, handing out letters to homes near the crime scene, pleading for witnesses to come forward. In the end, a witness and evidence from her son’s cell phone led police to the alleged killers — and gave Sumerlin and her family a moment of peace of mind.

“I have friends who have lost children and [it] didn’t turn out that way,” Sumerlin said earlier this week, hours after returning home for a bond hearing for one of the suspects. “I could never understand what it would be like, to not know why or who did something like that to my son.”