Since the New York Times published its recent series of bombshell articles about the crippling reparations that France imposed on Haiti after it won independence in 1804, much has been written about how this 150 million franc “indemnity” had virtually doomed the fledgling country before it had a chance to establish itself. The New York Times pieces outlined the huge long-term impact of these enforced payments and demonstrate that they cost the Haitian economy billions of dollars in lost economic growth, affecting the island well into the 21st century.

Historians of Haiti have remarked that the New York Times’ core claims are hardly groundbreaking. The long-term effects of the debt on the Haitian economy have long been acknowledged, researched and taught. Nevertheless the newspaper’s detailed account, with its additional evidence and fresh calculations, has allowed the story to achieve the kind of public visibility most professional historians can only dream of. This is undoubtedly positive.

But this account, for all its moral force and political relevance, also reinforces a longstanding public perception of Haitian history as a story of unremitting failure. Of course this is justified in many ways. To this day, Haiti remains one of the poorest countries in the world, for which France (along with the United States and others) bears undeniable responsibility. But Haitian independence deserves to be remembered for more than its long, tragic aftermath. It was, in fact, a stunningly innovative event which dramatically changed the course of world history.

Freedom fighters

Before the Haitian revolution, Saint-Domingue (as Haiti was then known) was France’s largest and richest colony. Its population primarily consisted of enslaved black people, who lived and worked under a small elite of white plantation owners. When the French revolution broke out in 1789, it triggered a series of revolts and conflicts on the island. These involved white colonists, black enslaved people, free black and mixed-race people, as well as the French, British and Spanish states.

By 1804, the black and mixed-race insurgents had joined forces and claimed victory. White colonists were driven out or killed. On January 1 1804 a former slave, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, proclaimed the independence of the island in the name of the Haitian people.

It was a complex, lengthy, shockingly violent process. For a long time, it was treated as a bloody footnote in Atlantic history, and left out of the triumphant accounts that narrated “the age of democratic revolutions”. But it is now increasingly being viewed by historians as a major turning point in world history. There are several reasons for this.

Emancipation in the New World

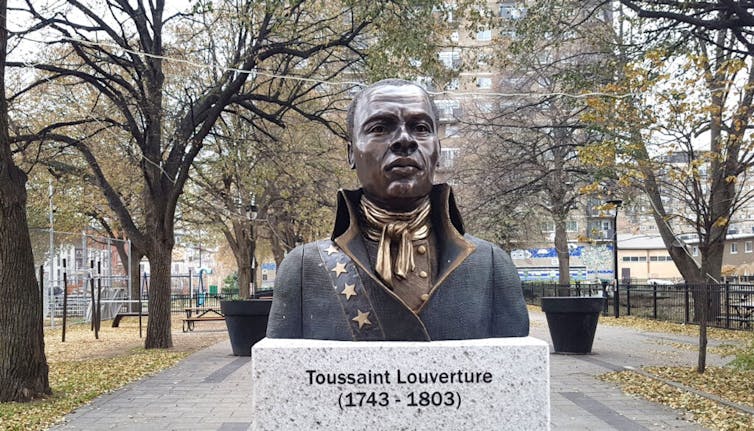

The first, and most immediately evident reason, relates to the history of colonial slavery. The Haitian revolution was a multifaceted conflict – but from 1791 its driving force was the great antislavery uprising spearheaded by the charismatic leader Toussaint Louverture. To this day it remains the only truly successful slave revolt in history.

It would be difficult to overstate the impact of the Haitian example on the history of emancipation in the New World. It raised the old spectre of slave rebellion and shocked slave owners across the Americas, but it also informed the British emancipation debate. In the 1810s the support Haiti provided to Simón Bolívar’s liberation movement played a major part in ending slavery in northern South America. Haitian emancipation also encouraged uprisings and rebellions in the US, Cuba and Barbados. It continued to inspire black people across the New World until the final abolition of slavery by Brazil in 1888.

The Haitian revolutionaries also durably transformed the international landscape. Emerging from an 18th-century world ruled by monarchies and colonial empires, Haiti became the first black republic in the world. It was only the second state to claim independence from a European empire, after the US.

Notably, it was the first to be ruled by formerly enslaved people. Independent Haiti was, in many ways, ahead of its time – it would take another century and a half for another significant decolonisation movement to emerge and finally topple the great European empires, in the second half of the 20th century.

Universal human rights

Amid all the tumult and upheavals of revolution, the Haitian people’s claim to independence was also philosophically groundbreaking. The Declaration of Independence of 1804 ended the Haitian revolution with a powerful assertion of national sovereignty:

We must, with one last act of national authority, forever assure the empire of liberty in the country of our birth … we must live independent or die.

By justifying independence in terms of the universal rights of mankind, Haitian leaders were deploying the same novel philosophical principles that underpinned the American and French revolutions. But, unlike the American and French republics, the new Haitian nation was to be rooted in its radical commitment to universal emancipation.

For all the above reasons, the Haitian revolution deserves to be remembered on its own terms – not only as the origin of a historical injustice, but also as one of the great revolutions of the Enlightenment, and a forerunner of modern decolonisation movements.

Anna Plassart does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.