Anthony Albanese received his fourth COVID jab this week. A commendable example to the community, now that eligibility for the “winter shot” has been widened.

Well, commendable up to a point. Noticeably, neither Albanese nor the health worker wielding the needle was wearing a mask, and the prime minister quickly came in for some flak.

Masks are currently a front-line topic in the debate about how we deal with the new COVID wave that is seeing an average of 45 deaths a day, taking deaths this year alone north of 8,000.

Earlier this week Victoria’s acting chief health officer recommended mandating masks in a number of settings, only to be rebuffed by the state health minister, Mary-Anne Thomas. She said it “was not the most effective way to get the message out about the importance of mask wearing”.

Masks have been a political and ideological football throughout the pandemic.

Unlike in many other countries, pre-COVID you’d not see Australians masked up except in hospitals and the like, so we weren’t used to them.

In the early stages of the pandemic, before the way COVID is transmitted was clearly understood, there was vigorous dispute among health experts about their efficacy.

Later, the general population accepted them, with various degrees of willingness or reluctance.

Some people dislike masks because of their inconvenience. One gets that.

But, more peculiarly, for the political right masks have become a culture war rather than a matter of effectiveness. Stephen Reicher, professor of psychology at the University of St Andrews, writing in the Guardian, argues that some who hold a certain world view see masks as “a potent symbol of control: they are muzzles”. What these people reject “is less the mask and more the political and scientific establishment that proposes it”.

Given current public opinion, the mandating of mask wearing will stay limited. But in view of their place in the anti-COVID tool box, it would be helpful if politicians remembered to lead the way when appropriate.

We have reached a hinge point in the pandemic, and the weeks ahead present a huge challenge for political leaders. The community has moved on from COVID. But COVID has not moved on from the community. It has dug in.

A mind reset is needed. But that’s hampered by many in the public and in the political class being unwilling to accept that we haven’t “pushed through” to “live with COVID” in a safe sort of way. To the extent we are “living with COVID” we are accepting a crisis in the hospital system and a level of deaths that, if it had occurred in 2021, would have generated a massive reaction.

The earlier wisdom was that when the population was highly vaccinated, the situation would be under control. But it hasn’t worked out like that.

Vaccination is limiting the seriousness of the illness for most; it cuts deaths in relative terms.

But it hasn’t been successful against transmission, which means the virus is spreading like wildfire (currently hundreds of thousands have it). In absolute numbers, many people are getting quite sick, and there will be a good deal of “long COVID”.

The Albanese government has launched initiatives, including a campaign to urge boosters and action on anti-virals. But it’s like chasing a fleet-footed tiger.

And the government has refused to extend the emergency payment for workers forced to stay home, or the free RATs for concession card holders. It cites the budget. But we can imagine what Labor would be saying if it were still in opposition. There is some stirring within Labor ranks, with NSW Opposition Leader Chris Minns and federal backbencher Mike Freelander (a doctor) saying the emergency payment should be restored.

The new situation has caused havoc with what in 2020 was that (mostly) widely welcomed line from politicians that “we follow the expert advice”.

It’s been a roller coaster for the experts. Lauded and leaned on initially, they then ran into rougher times. They argued among themselves. They were dragged into the politics and demonised by critics who thought the politicians were listening too much to them.

Now we’re seeing the politicians grabbing back their agency, as the experience of the Victorian health official showed. More problematic, the politicians, including federal Health Minister Mark Butler, are making it clear the experts have to operate in the real world of where we’re up to with community opinion.

While this seems sensible at one level, things become complicated. When we get a piece of “expert” advice, do we assume it’s unadulterated, or a sort of shandy – containing a dash of “real world” lemonade?

There is also some counter-intuitive action at the “expert” level. With large numbers of deaths occurring in aged care homes, the NSW chief health officer, Kerry Chant, this week signed a public health order making it no longer mandatory for visitors to these facilities to be vaccinated. This is in line with the situation in Victoria and Queensland but the timing seemed odd.

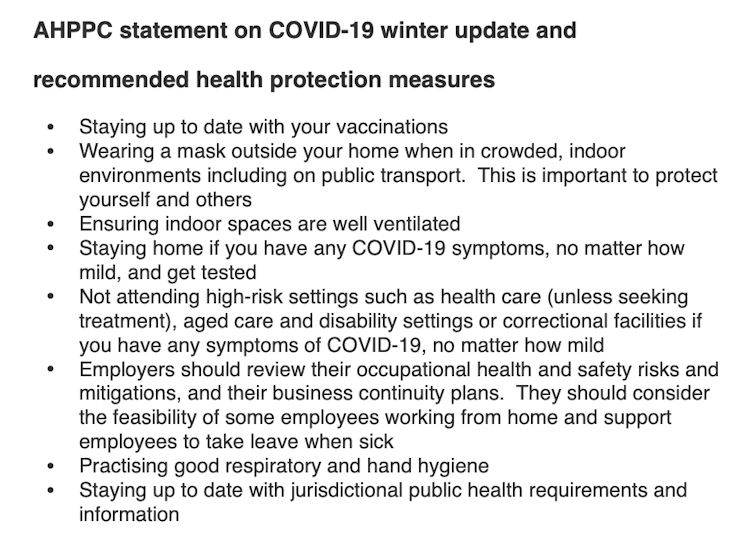

It came as the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC), consisting of federal and state chief officers, last week reminded “individuals, employers and governments” of their shared responsibility to minimise the impact of COVID.

The question is whether political leaders have either the will or the ability to inject new urgency and potency into the fight against COVID, given the only practical weaponry in this time of pandemic fatigue is “light touch” ammunition.

Brendan Crabb, director of the Burnet Institute, who is highly critical of how the pandemic has been allowed to run away, says leaders and health ministers at national and state levels should admit the mistakes of this year.

“For the last six months we just tried to protect the old and the immunocompromised,” he says. “We didn’t address transmission.”

Any sort of mea culpa mightn’t be so hard at the federal level, where the new government can blame the former one, but it’s another matter in Victoria and NSW, where governments face elections soon.

Beyond that, Crabb is essentially arguing for more energy to be put into the struggle against transmission. He points to the Biden administration intensifying its efforts, and the AHPPC’s exhortation.

Business doesn’t like a strong focus on COVID, even though fast transmission is doing it immense damage. Even if we are well beyond lockdowns and (mostly) beyond mandates, business fears the impact of, for example, Victorian advice this week for people to work from home. But Crabb argues business should be in favour of a range of these less drastic measures to try to keep transmissions low, because it suffers from the high rates of infection.

Crabb says that “bringing the community along” is crucial. “A part of that, of showing you’re serious, is leaving no one behind.” He says making available high-quality masks, RATs and support to isolate “are not only essential if the interventions are to take hold, they are the litmus test of the government’s seriousness.

"COVID is one of the biggest issues the country faces at the moment, but the country doesn’t know it.”

To elevate that awareness Albanese – who has agreed to a national cabinet meeting on Monday on COVID – will need personally to become much more central in the messaging.

Michelle Grattan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.