In journalism, bad news sells. “If it bleeds, it leads” is a famous industry catchphrase, which explains why violent crime, war and terrorism, and natural disasters are ubiquitous on TV news.

The fact that journalists and their employers make money from troubling events is something researchers rarely explore. But even if it seems distasteful, the link between negative news and profit is important to understand. As a media historian, I think studying this topic can shed light on the forces that shape contemporary journalism.

The assassination of John F. Kennedy 60 years ago offers a case study. After a gunman killed the president, television news offered wall-to-wall, nonstop coverage at considerable cost to the networks. This earned TV news a reputation for public-spiritedness that lasted decades.

This reputation – which may seem surprising now but was widely accepted at the time – obscured the fact that TV news would soon become enormously profitable. Those profits are due in part because awful news attracts big audiences – which remains the case today.

The JFK assassination made Americans turn to TV news

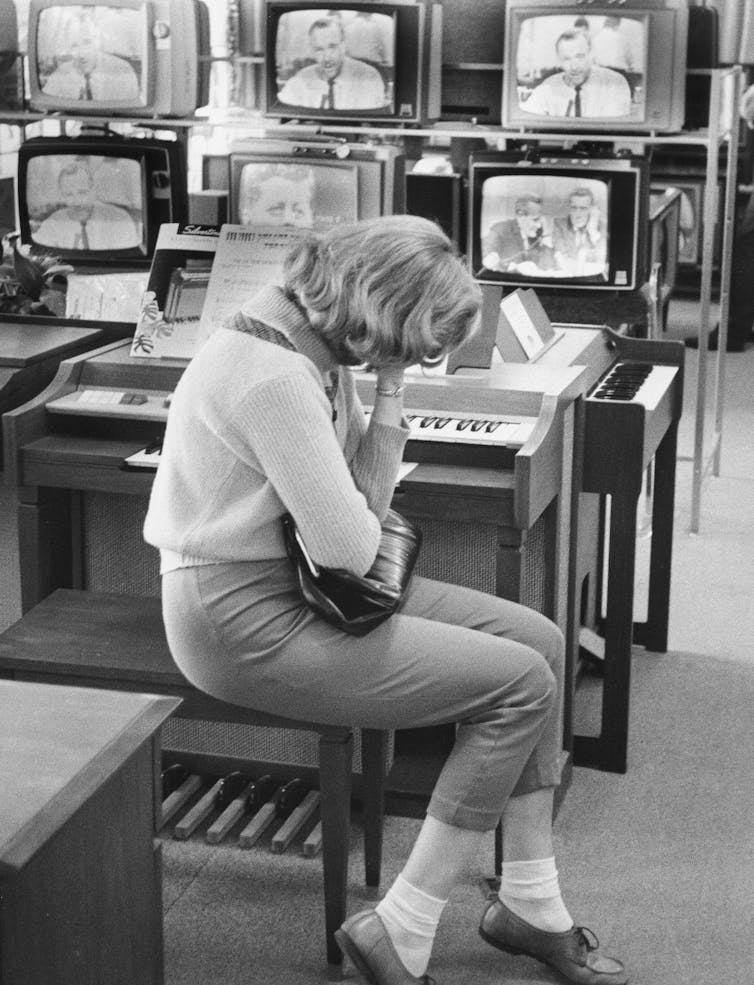

Shortly after Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963, the TV networks demonstrated their sensitivity to the tragedy by canceling commercials and devoting all their airtime to the story for several days. CBS President Frank Stanton would later call it “the longest uninterrupted story in the history of television.” At one point, 93% of all U.S. TVs were tuned into the coverage.

Estimates vary, but the networks’ decision to forgo ads may have cost them as much as US$19 million – which is $191 million in 2023 dollars.

For decades, the networks presented their assassination coverage as the epitome of public service. And over and over, network executives and journalists argued that TV news was uniquely protected from the economic pressures found elsewhere in broadcasting.

TV news in the early 1960s was “the loss leader that permitted NBC, CBS and ABC to justify the enormous profits made by their entertainment divisions,” ABC News’ Ted Koppel reminisced in The Washington Post in 2010. He added, “It never occurred to the network brass that news programming could be profitable.”

The public-service narrative that took root in November 1963 ignored the fact that the huge audiences turning to TV news for information and comfort would soon become very lucrative.

How TV news became a money machine

Only two months before Kennedy’s assassination, in September 1963, the networks expanded their evening newscasts to 30 minutes. They had previously been 15 minutes, offering little more than headlines. The expanded newscasts sold out all their advertising opportunities immediately, as television news drew the predictable daily mass audiences that sponsors craved.

The Kennedy assassination coverage, combined with the expanded newscasts, significantly increased the commercial value of TV news. Throughout the 1960s, broadcast journalism began to mature into the most lucrative genre of programming on American television.

By the 1965-1966 television season, NBC’s “The Huntley-Brinkley Report” generated $27 million in advertising a year, making it the network’s most lucrative program – out-earning even “Bonanza,” the top entertainment show. “The CBS Evening News” was drawing in $25.5 million in advertising, making it the second-most profitable program on U.S. television.

Around this time, networks were telling regulators that they had sacrificed millions of dollars for public service through journalism. For example, in 1965 testimony before the Federal Communications Commission, executives from ABC, CBS and NBC said their news divisions had loftier motives than simply making money.

But they were making money, and lots of it. By 1969, “Huntley-Brinkley” was earning $34 million in advertising on a production budget of $7.2 million, making the program – according to Fortune magazine – “the biggest source of revenue that the N.B.C. network has – bigger than ‘Laugh-In’ or ‘The Dean Martin Show.’” A decade earlier, “Huntley-Brinkley” had been making just $8 million in ad and sponsorship revenue.

The networks didn’t tout their profits, though. Instead, they continually promoted their efforts covering the Vietnam War, civil unrest and the assassinations of the 1960s as service in the public interest. They also claimed that news production cost them millions, and they hid ad revenues accrued by news programming elsewhere in their corporate budgets. Doing this gave them a leg up on regulatory privileges, such as station license renewals.

The birth of modern TV news

Ultimately, the chaotic, cacophonous and confusing decade of the 1960s would end up launching the hyper-commercial media world we live in today. Chasing sensational investigative stories, such as Watergate and the Iran-Contra arms-for-hostages scandal, would generate higher ratings and more advertising revenue, and turn broadcast journalists into national celebrities.

The original values animating network broadcast journalism at its inception would surrender to more lucrative formats. “60 Minutes” – a CBS News production – eventually became the most valuable network-owned programming property in the history of American television, and by the 1980s almost every local news station had launched its own “I-Team” investigations group.

Eventually, the professionalism that drew audiences to TV news in the wake of the Kennedy assassination in 1963 would be supplanted by audience growth strategies sold by TV news consultants. Audience analytics, minute-by-minute engagement metrics and Q-scores calibrating anchor “likability” would standardize formats and homogenize newsgathering in the drive to maximize profits.

Yet through the decades, one constant remains: Bad news sells. It’s a media-industry truism whether we’d like to study it or not, and the news broadcasts airing today, 60 years after the events of November 1963, prove it.

Michael J. Socolow does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.