A global episode of heat-related coral bleaching has grown to the largest on record, US authorities said Friday, sparking worry for the health of key marine ecosystems.

From the beginning of 2023 through October 10, 2024, "roughly 77 percent of the world's reef area has experienced bleaching-level heat stress," Derek Manzello of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) told AFP.

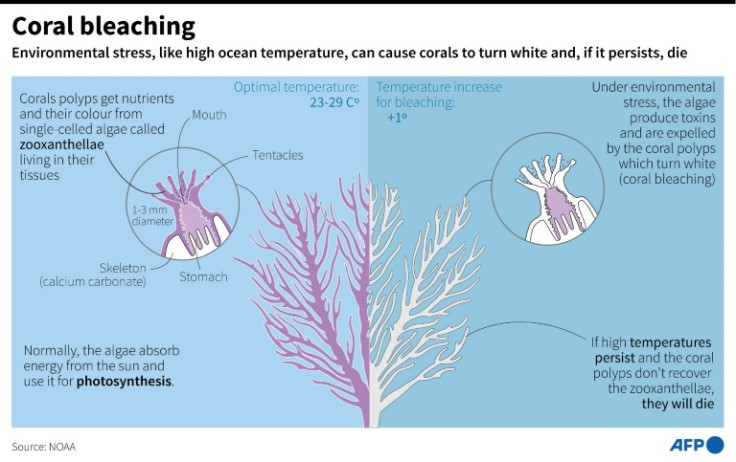

When ocean water is too warm -- such as during heat waves which have hit areas from Florida to Australia in the past year -- coral expel their algae and turn white, an effect called "bleaching" that leaves them exposed to disease and at risk of dying off.

The algae provide coral with food and nutrients, as well as their their captivating colors.

Manzello said the ongoing bleaching event -- the fourth since 1998 -- had surpassed the previous record of 65.7 percent in half the time, and "is still increasing in size."

The consequences of coral bleaching are far-reaching, affecting not only the health of oceans but also the livelihoods of people, food security and local economies.

Severe or prolonged heat stress leads to corals dying off, but there is hope for recovery if temperatures drop and other stressors such as overfishing and pollution are reduced.

The last record had been set during the third global bleaching event, which lasted from 2014 to 2017, Manzello said, and followed previous events in 1998 and 2010.

NOAA's heat-stress monitoring is based on satellite measurements from 1985 to the present day. It declared the latest mass bleaching event in April 2024.

Pepe Clarke, with the environmental nonprofit WWF, said at the time that the "scale and severity of the mass coral bleaching is clear evidence of the harm climate change is having right now."

Manzello on Friday said NOAA had confirmed reports of mass coral bleaching from 74 countries or territories since February 2023.

"This includes locations in the northern and southern hemisphere of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans," he told AFP by email.

Australian authorities announced in March that the famed Great Barrier Reef was experiencing its fifth mass bleaching event in eight years.

"Corals can recover if the marine heat stress is not too severe, or too prolonged," Manzello and colleague Jacqueline De La Cour told AFP in April.

But there are "lasting physiological impacts for the survivors" and recovery "becomes increasingly challenging as bleaching events become more frequent and more severe," the pair added.

Coral are marine invertebrates made up of individual animals called polyps which have a symbiotic relationship with the algae that live inside their tissue.

The EU's Copernicus climate monitor reported last month that more than 20 percent of the world's oceans experienced at least one severe to extreme marine heatwave in 2023.

The average annual maximum duration of such a heat event has doubled since 2008 from 20 to 40 days, its "Ocean State Report" said.

More broadly, it also warned that the pace of ocean warming has almost doubled since 2005, as global temperatures rise because of human-caused climate change.

The confirmation of the new record comes just ahead of a major UN biodiversity summit in Colombia, where an emergency special session has been called on the sidelines to discuss the mass bleaching event.

Global stakeholders will present up-to-date scientific analysis at the event and discuss efforts at "thwarting functional extinction" of reefs, according to an invitation.