It's like I've face-planted into a giant colour palette. Picking myself up off the ground, there are wildflowers in every direction I look. Pink, white, mauve, yellow and every shade between.

I'll try and pay more attention where I plonk my foot next time, but it's hard not to be distracted when walking through such an inspiring landscape. The kaleidoscope of alpine blooms reminds me of a pre-COVID family trip to the German Alps to the very location where The Sound of Music was filmed. Only here, the hills aren't alive with Julie Andrew's melodic cadence, rather the low-pitched hum of those denizens of summer in the high country - march flies.

As a pollinator of the wildflowers, you know if there are lots of march flies that it's a bumper year for wildflowers and vice versa. But I'm not going to let a shoe full of water and a few irritating flies prevent my quest to find the ruins of the Mason Moraine Shelter, a roofless, three-walled stone refuge squirreled away in backcountry near Charlotte Pass.

If you haven't heard of it, you're not alone. Not many have.

It's the sort of place whispered about around campfires late at night, a mythical stockman's shelter. Only it's no legend. It's real.

One of the few written references to the "intriguingly anonymous shelter" appears in Bold Horizon: High-country Place, People and Story (Rosenberg, 2018) where author Matthew Higgins describes it as "quite possibly erected during the nineteenth century" as "a rampart against the ferocious winds from which stockmen sheltered in the days before grazing was prohibited around these highest peaks in the 1940s".

Klaus Hueneke, who has written extensively about the huts of Kosciuszko National Park, is also at a loss as to its exact origins. "There are no records of it in the old ski yearbooks, which is surprising because the early skiers of the 1910s and 1920s explored most of that country. It could date to the late 1800s, but none of the people I interviewed for my books knew about it. Someone went to a lot of trouble to move all those rocks to build it, so while it is likely it was a built by stockmen, who knows, it could have been built by some early European explorers as well, it's a bit of a mystery."

Apart from Higgins and Hueneke, one of the few people I know to have trekked to the remote rock shelter is Stef De Montis, which isn't unexpected, given he's spent much of the last 15 years exploring the roof of Australia on foot.

"I remember stumbling across it in 2010, it was one of the sites that got me really interested in the history of the of mountains and set me on the path I'm on today. A bit of mystery and unlike anything else up there," he explains.

When I mentioned to De Montis that I wanted to check it out for myself, he told me to walk for a few kilometres along the Summit Trail from Charlotte Pass and then head off track towards Mt Clarke.

It turns out his mud map was spot on, which is a good thing, for set into the side of the hill, the remains of the shelter are very well camouflaged. So well, that every year, while walking up to Seamans Hut and beyond to Mt Kosciuszko, thousands of people would pass within direct view of it, albeit some distance away.

With a footprint of about 4.5m wide by 10m long, it's only when you get right up to it that you get a real feel for its size. Although the northern end is exposed to the elements, it would provide welcome relief from the howling gales which in these parts often blow in from the south and west.

On the ground near the longer and higher of the three walls and beneath what appears to be a recess for a fireplace is a long piece of weathered timber. When conservation architect David Scott visited here in 1991, he recalls "it was on top of the fireplace recess like a lintel or mantlepiece".

Further, Scott suggests "the roof was likely a calico or canvas tarpaulin strung from a sapling post (now gone) at each end, of a gable form that abutted a tall end wall at the fireplace and where the sides sat on top of the walls and were anchored by guy ropes or simply weighed down with stones. The northern end may have always been open or closed off with a canvas flap."

Still brushing away the flies, I notice a rusted tin can wedged into one of the well-laid drystone walls. It may have been found half-buried nearby and placed there by a recent adventurer or perhaps it was discarded in more recent times. Who knows, like the exact origins of the shelter, it remains a mystery. It's always best to leave such items in situ as it helps archaeologists to interpret a site.

One thing is for sure, the stockmen who hunkered down in this rudimentary shelter were unlikely to have enjoyed the spectacular view I do today - the cattle that grazed this part of the high country until the early 1940s would have trampled (or eaten!) most of the wildflowers. On the plus side, they may not have had to endure as many march flies.

If you know anything about the Mason Moraine Shelter, or have stumbled across similar ruins in the bush, please let me know.

Lake still a long way from full, no matter how you measure it

As more Canberrans drive past a filling Lake George, I'm receiving an increasing number of questions about just how much water is currently in the lake. "Is it full yet, it must be close?" is the most common question.

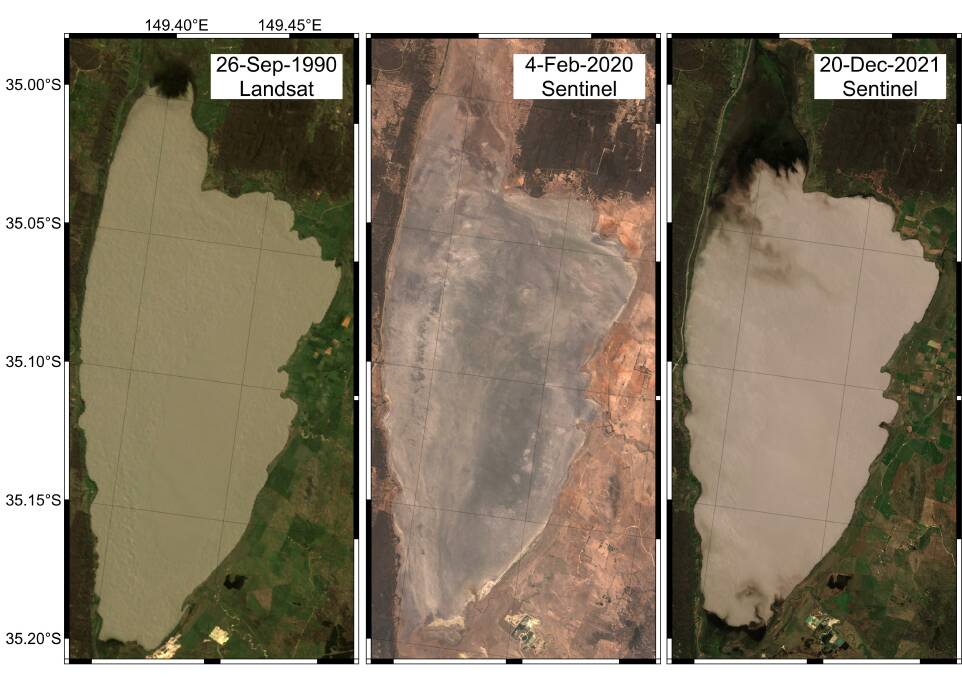

Just "how full" the lake is, isn't easy to answer because Lake George is an endorheic lake which means it has no evident outlets. It's a bit like asking how long is a piece of string. However, according to Michael Short, lead author of a Two Centuries of water-level records at Lake George, NSW (Australian Journal of Earth Sciences, September 2020), one way to gauge just how full the lake is, is to compare it to past levels. But even that is tricky.

"The first reference to compare current levels to is the greatest height since the satellite era (1987 to now), which was about 2.6m in September 1990," explains Short. Using this method, the lake currently sits at about 1.8m so is about two-thirds full. "On a volume basis, the current volume is about 150GL, and compares to about 270GL in 1990," he says, adding "so it's currently a little over half-full by volume."

The second reference period for a "full lake" is the highest level in the last century which was about 4.6m (580GL) in 1956 and makes today's level a little less than half by height and about a quarter by volume.

A third and final possible reference point is the highest recorded level of a whopping 7.4m (680GL), which was in 1874, reveals Short. "In comparison, today's level is about a quarter by height and about a fifth by volume."

Short thinks the best comparison is to the highest level of the satellite era "because it is still within the same 30-year climate period".

"However, it'd be amazing to see the rain continue, and the lake reach heights not seen in over a century," he exclaims. Hear hear!

WHERE IN THE REGION?

Rating: Difficult

Cryptic Clue: Aye aye captain!

Last week: Congratulations to Leigh Palmer of Isaacs who was the first to correctly identify last week's photo as "Puggle", the 110-metre-long platypus geoglyph at Namarag Nature Reserve in the Molonglo River Reserve.

If you haven't checked it out yet, Namarag (wattle in Ngunnawal language) Nature Reserve celebrates Canberra's Ngunnawal heritage with storytelling through art woven throughout the park's landscape. Adults can follow the story of the bogong moth told on a huge scale through interpretive signage while kids will enjoy the knock-out nature playground with interactive play items like the one-of-a-kind wedge-tailed eagle nest.

The platypus (malunggang in Ngunnawal language) is an important cultural totem and the geoglyph, which is best viewed from the air and covers an area of 1500m2, was created using landscape restoration techniques including native grass seeding and rock-lined plantings.

"They've used rocks around the perimeter, boulders for the eyes and nostrils, logs for the claws, and native grass for the body," reports Craig and Karen Collins of Coombs, two local Waterwatch volunteers who after being enamoured by the valley's first geoglyph, an oversized wallaroo scraped into the earth three years ago, urged Park authorities to design even more geoglyphs for the river corridor.

The Namarag Nature Reserve is best accessed from the car park on the western side of John Gorton Drive, about 500 metres south of Coppins Crossing. If you go, look out for several other geoglyphs in the reserve, including a giant lizard and pink tailed worm lizard.

How to enter: Email your guess along with your name and suburb to tym@iinet.net.au. The first correct email sent after 10am, Saturday February 5, 2022, wins a double pass to Dendy, the Home of Quality Cinema.

SIMULACRA CORNER

Still on monotremes (egg-laying mammals that include the platypus and four species of echidna); while recently beachcombing at Broulee Island, Bob Gardiner of Isabella Plains stumbled upon this hitherto "undescribed species of semi-aquatic echidna" lurking in a rock pool. "It must have been fossicking around for tucker, presumably oysters," muses Bob. Can you see it?