From its mandolin-making origins to today’s status as one of the most iconic guitar brands in the world, Gibson has seen its fair share of brave new shapes, sounds and technologies, alongside the rise and fall of its fortunes, over the past 130 years.

Here, we highlight 20 of the company’s most defining moments.

1902: Birth of the Gibson company

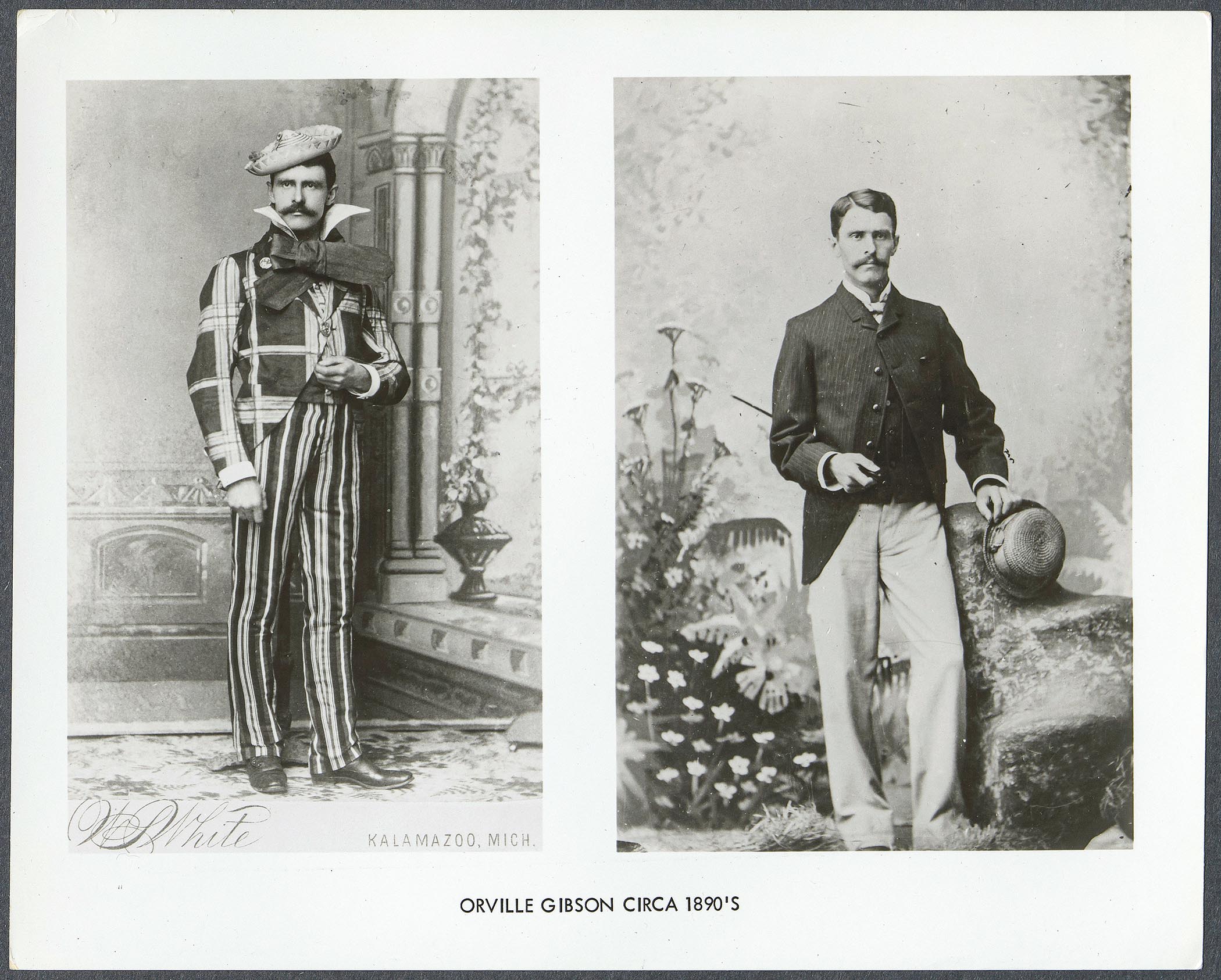

Around 1880, Orville Gibson moved from his native New York State to Kalamazoo, Michigan. He developed an unconventional mix of ideas and methods to make his mandolin-family instruments and guitars, starting in the mid-1890s – with the company today marking 1894 as the year of its inception.

He did not use internal bracing. Instead, he would carve his tops and backs, and rather than the usual heated-and-bent sides he’d saw the sides from solid wood.

In 1902, Orville sold out to a group of five businessmen who formed the Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Manufacturing Company. Orville left soon afterwards, receiving a regular royalty for five years and then a monthly cheque for $41.66 until his death in 1918.

1922: L-5 archtop introduced

Gibson had shifted from Orville’s idiosyncratic creations to produce reliable models such as the L-4 archtop (1912) and the Nick Lucas flat-top (1927), although at first the company’s emphasis was on mandolins and then banjos, for a time the most popular stringed instruments.

Lloyd Loar’s Master Series L-5 guitar of 1922 defined the contemporary archtop, apparently more akin to violins than guitars. The L-5 had a carved arched top, two f-holes instead of a single round soundhole, a floating height-adjustable bridge with strings fastened to a separate metal tailpiece, and a neck-strengthening truss rod.

1934: Guitars take centre stage

The growing popularity of the guitar made it the focus of Gibson’s efforts during the 30s, leading inevitably to bigger, louder, improved instruments.

There were two key introductions in 1934: the Jumbo flat-top, which together with the Advanced Jumbo (1936) and the J-45 (1942) established Gibson’s slope-shouldered style; and the Super 400, the brand’s impressive top-of-the-line acoustic archtop that was the biggest and flashiest of its kind at launch.

Meanwhile, the J-200 (1938) would become another long-lived Gibson flat-top, introducing the narrow-waist style often known by the 200’s original name, Super Jumbo. By now, Gibson was the market leader among American guitar makers.

1935/’36: First electric models

At the end of ’35, the Kalamazoo firm introduced the EH-150 steel and amp set, its first foray into electric instruments. The ES-150 followed late in ’36, marking the start of Gibson’s remarkable history of electric guitars.

It was also the beginning of the company’s long-running ES series, the letters standing for Electric Spanish – with ‘Spanish’ referring to a guitar played in what we now consider regular style, as opposed to the on-the-lap Hawaiian steel style.

The budget ES-100 appeared in ’38, fitted a couple of years later with a new pickup with adjustable polepieces, and in 1940 Gibson launched its most expensive pre-war electric model, the ES-300, with an angled pickup that accentuated bass and treble.

1944: CMI acquires Gibson

Maurice Berlin’s Chicago Musical Instrument Company acquired a controlling interest in Gibson, with the manufacturing base staying at the original factory in Kalamazoo, roughly equidistant between Chicago and Detroit. Gibson’s sales and admin departments were moved to CMI headquarters in Lincolnwood, a suburb of Chicago.

As Gibson gradually increased instrument manufacturing after the deprivations of World War II, the electric guitar would become a vital part of its reactivated business. Musicians and other guitar makers took serious note of what the market leader was up to, and Gibson’s firm commitment to the future of the electric instrument marked an important step in its wider acceptance and technical development.

1952: Les Paul Model launched

Fender’s activities over on the West Coast with a new-fangled solidbody electric were not lost on the bosses at Gibson HQ. Soon, company president, Ted McCarty, was negotiating with Les Paul, probably the most famous guitarist in America thanks to big hit records, and a plan emerged for Les to endorse Gibson’s first solidbody Spanish.

The Les Paul Model was introduced in 1952. With its carved top and fancy gold finish, it was designed to reflect Gibson’s craft heritage, in contrast to Fender’s straightforward, unpretentious approach.

Three models would complete the Les Paul line – Custom, Junior (both 1954) and Special (1955) – and the Goldtop famously switched to a sunburst finish (1958 to ’60).

1953: Debut of the Tune-o-matic bridge

The Tune-o-matic was Gibson’s first fully adjustable bridge, introduced in ’53 on high-end electric archtops and the following year on the new Les Paul Custom.

Fitted in conjunction with a bar-shaped tailpiece, the bridge had two adjustment wheels for overall height adjustment, and six brass saddles with screws that, for the first time on a Gibson, offered individual adjustment of string length, improving intonation.

Ted McCarty’s name appeared on the patent, assigned to Gibson – though that doesn’t necessarily mean he was the sole designer of the bridge, which more likely was devised by various members of the Gibson team.

1957: PAF humbucking pickup introduced

In Gibson’s electronics department, run by Walt Fuller, Seth Lover came up with a new pickup model. For Gibson’s take on the humbucking idea, Seth wired together two coils, with opposite magnetic polarity, connected in reverse so the current travelled clockwise around one coil and anti-clockwise around the other.

The coils were out of phase, the magnets were out of phase, and the resulting pickup was in phase, but any 60-cycle hum was out of phase and cancelled. Starting in the early months of ’57, Gibson began to put the new humbuckers in place of its P-90 single coils on many models, including the Les Paul Goldtop and the Custom, which was promoted from two P-90s to three humbuckers.

1957: Gibson acquires Epiphone

Epiphone had been Gibson’s nearest rival in American guitars in the ’30s and ’40s, but by the late ’50s Epi was in trouble. Gibson bought the brand in 1957, relocating the operation to its Kalamazoo base.

By ’59 Gibson was shipping its new Epiphones, made in the Kalamazoo factory to the same quality as Gibsons but as an independent brand with its own dealer network and a line that in part filled gaps in the Gibson range.

The differences were mainly down to pickup types, tailpieces and vibratos, and decorative styles. By 1969, Epiphone production would be switched to Japan, and the brand’s identity as Gibson’s important second marque only grew in the following decades.

1958: Explorer & Flying V, ahead of their time

Until the Flying V and Explorer, electric guitars were supposed to look… like guitars. You know, a strongly curvaceous outline and a sense of historical heritage. Gibson turned conventional design upside down by using straight lines and angular body shapes, changing the way electrics could look and, in the process, creating a rare set of future collectibles.

Famously, the new guitars were not a success – for now, at least. “Try one of these ‘new look’ instruments,” the original publicity insisted. “Either is a sure-fire hit with guitarists of today!” That, however, was not the case. It would be the guitar players and guitar designers of tomorrow who would make them a hit.

1958: The fabulous hybrid 335

Gibson’s most revolutionary guitar design, the ES-335 was a true first for the company: a double-cutaway thinline semi-solid electric guitar. Sales of its solidbody models had slipped a little, so the idea was that a guitar with the benefits of a solidbody in a hollowbody-like package might prove more appealing to wavering players.

The secret was hidden inside the 335, namely a solid block of wood running through the inside of the otherwise hollow body. Guitarists have crowded around ever since to taste the 335’s attractively different flavours. Gibson again developed a line from the core model with the addition of three more: the high-end ES-355, stereo ES-345 and fully hollow ES-330.

1960: New folkie flat-tops

Not only did these attractive new flat-tops sit well with the resounding folk boom of the era, but they lined up as the first Gibson acoustics to compare closely, shape-wise, to Martin’s venerable dreadnoughts. That’s why in later years these models would often be grouped together as “square shoulder” types, in contrast to Gibson’s existing “slope shoulder” style, like the J-45.

The Hummingbird appeared first (1960), with 24.75-inch scale and mahogany back and sides, followed by the Dove (1962), with 25.5-inch scale and maple body. They looked the part, too, especially those engraved pickguards with cute little birdies fluttering among the greenery. Songbirds, indeed.

1960: Move over Les Paul, here’s the SG

The new SG solidbody design was a radical amalgam of bevels and points and angles, inviting players to reach the topmost frets with ease and speed. Gibson had decided the original single-cut Les Paul design was old hat and the SG would replace it. Luckily for us, both would survive longterm.

The first two SGs – for now still named the Les Paul Standard and the Les Paul Custom – were announced in the early months of 1961, though production of the Standard started late in ’60. In 1963, Gibson finally dropped the remaining Les Paul names, establishing the new line as the SG TV, SG Junior, SG Special, SG Standard and SG Custom.

1963: Firebirds take off in reverse

Gibson called on a retired automobile designer, Ray Dietrich, to style the new Firebirds launched in ’63. The I, III, V and VII each had different appointments but followed the same design and build. Rather than Gibson’s customary glued-in set neck, they had a through-neck construction.

Standard finish was sunburst, but Gibson went further than simply adopting Fender-like shapes for the new line and borrowed its rival’s custom finishes idea, offering Cardinal Red, Frost Blue, Inverness Green metallic and more.

Production hiccups would lead to a redesign in ’65, with a noticeably different body shape (known as ‘non-reverse’, rather than the earlier ‘reverse’ style) and a regular set neck.

1969: Gibson under Norlin management

Norlin Industries was formed in 1969 with the merger of Gibson’s parent company, CMI, and an Ecuadorian brewery, ECL – ‘Norlin’ came from the combined names of Norton Stevens, ECL’s chairman, and Maurice Berlin, CMI’s founder.

The takeover would be formalised in ’74, and Berlin was shifted away from running the company. Norlin favoured cost-cutting and simplified production, and changes were made to some Gibsons built into the ’70s.

A new Gibson factory in Nashville opened in ’74, and the original Kalamazoo plant was closed 10 years later. Some guitarists felt that these changes converged to create a dip in Gibson quality and innovation.

1980: Les Paul Heritage and Gibson history

The value of Gibson’s past began to dawn on the company, and the idea took hold that recreating earlier features and models might appeal to guitarists who were now paying increasingly large sums for ‘vintage’ instruments.

A hint came with the ES-335 Pro (1979), the first 335 with dot markers since the change to blocks in ’62, the first with a stop tailpiece since the trapeze of ’65.

The Les Paul Heritage (1980) marked the first proper attempt to emulate more of that past glory, with revised humbuckers and corrected neck material, body shape and top-carve shape. It wasn’t perfect yet, but it paved the way for the far-reaching reissue programmes Gibson would develop in the decades that followed.

1982: Chet Atkins CEC introduced

The CEC marks a rarity in the more recent history of Gibson because it was a brand-new style of guitar: a semi-solid electric classical. Despite his reputation as an electric player, Chet Atkins was by the 80s mostly playing nylon-string classical-style flat-tops, and he was on the hunt for a practical electric model.

Amplifying acoustic classical guitars didn’t work well for him, so he took his quest to Gibson. The result was the CEC, with a classical-like fingerboard width (there was a narrower version, the CE), a thin semi-solid body and a piezo bridge pickup, and it mostly looked and felt something like a classical guitar – only louder and without feedback tendencies.

1986: Norlin sells Gibson to new buyers

Norlin decided during the early ’80s that it would sell Gibson. Sales had fallen by 30 per cent in 1982 to a total of $19.5 million, against a high in ’79 of $35.5 million.

The guitar market was in trouble, and most American makers were suffering in broadly similar ways – costs were high, economic circumstances and currency fluctuations were against them, and Japanese competitors had an edge. In 1985, Norlin found a buyer.

Three businessmen who had met while classmates at Harvard business school, with Henry Juszkiewicz at the helm, completed their purchase of the Gibson operation in January ’86 for $5 million. It would at times be a bouncy ride.

1989: Shifting production sites

Among the changes that Juszkiewicz and his team introduced – some welcome, some less well received – was the establishment of some new production facilities.

Gibson acquired the Flatiron mandolin company of Bozeman, Montana, in 1987, and in ’89 production of Gibson flat-tops moved to a new factory at the site. In 2000 Gibson opened another new factory, in Memphis.

The Nashville factory was working at full capacity, so solidbody production stayed there, with the new building dedicated to ES models. However, the Memphis plant was closed in 2019 following Gibson’s filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2018, and all electric guitar production was consolidated once again at Nashville.

2018: Another new owner for Gibson

Gibson emerged from its bankruptcy protection in November 2018, with KKR the new majority owner with controlling interest in the company. JC Curleigh was appointed president and CEO, joining Gibson from Levi Strauss & Co, with further appointments including Cesar Gueikian as CMO. Gueikian superseded Curleigh as president and CEO in 2023.

The new owners seem today to be steering Gibson on a steady course after the choppy waters of earlier years. Successes include the creation of the Murphy Lab, a division of the Custom Shop headed by relic pioneer Tom Murphy to build historically accurate guitars, and a clarification of Gibson’s lines into logical groupings, with electrics divided into Original and Modern, for example. Here’s to another 130 years!