According to its opening credits, the new Channel 4 documentary Ghislaine Maxwell: The Making of a Monster has the advantage over its many equivalents because, in it, “those who know her come forward to reveal the truth about Ghislaine Maxwell”.

This is true, though you get the impression some knew her far better and for far longer than others – and the “truth” some did speak was more in the nature of what m’learned friends call “hearsay”. A high proportion of those who knew Maxwell went on to become journalists or writers, which, in my opinion, means they know how to deliver an anecdote. The “truth” I suppose is that very few people were ever truly close to the “socialite”, and the two who knew her best – her father, Robert Maxwell, and her lover/employer, Jeffrey Epstein – are dead.

What is completely unsurprising is that none of those who knew Maxwell have an unalloyed good word to say about this perverted monster. People willingly attest to her intelligence and beauty, and her ability to organise a party, but never without qualification. It probably would have made TV history if Ghislaine Maxwell: The Making of a Monster had been a compilation of all her old mates saying she wasn’t a bad old stick after all, that she was kindly, that she “got the big calls right”, that sort of thing. It’d be like the affectionate inscriptions scribbled in those oversized leaving cards – signatures with kisses or a heart next to them – something Maxwell could cling to in the penitentiary she’ll call home for the next 20 years. But the rehabilitation of Ghislaine Maxwell awaits a braver, more ambitious team of producers.

A word that keeps cropping up in this first of three instalments, which covers her childhood to early adult life, is “rude”. Aside from being “rude”, she also “didn’t do enough work” (Michael Crick); was “a spoiled brat, abrupt and demanding” (Anne-Elisabeth Moutet); “a ridiculous person with an inflated ego” (Christina Oxenberg); and, of course, a “Queen Bee” (Anne McElvoy).

These assembled journalists and writers all confirm the consensus view that, in personality if not in build, Maxwell was a chip off the old block. She emulated press baron Robert Maxwell and learned some of his confidence tricks. After the shock of his death in 1991, she sought out a replacement for him, one whom she could please and whom, in return, would maintain her in the lavish lifestyle she’d grown accustomed to. It wasn’t much more complicated than that, amoral as it all was.

There are certainly harrowing revelations, despite the mostly well-known litany of exploitative inhumanity. Oxenberg, seemingly the closest of the interviewees to Maxwell, tells of how she organised a party at her father’s stately home, where they played an unusual after-dinner “game”. The male guests were issued with blindfolds, while the women were asked/told by their hostess to remove their tops and bras. They were then presented to the men who, assessing weight and estimated cup size, tried to identify which female the breasts were attached to. Oxenberg avoided taking part and, as she drily remarks, the episode “left me wondering about what was going on with her”. This abnormal, dehumanising attitude to young women as sexual objects was to frame the rest of Maxwell’s life. The point is that she was at least on the road to such corruption long before she encountered Epstein and supposedly fell under his spell.

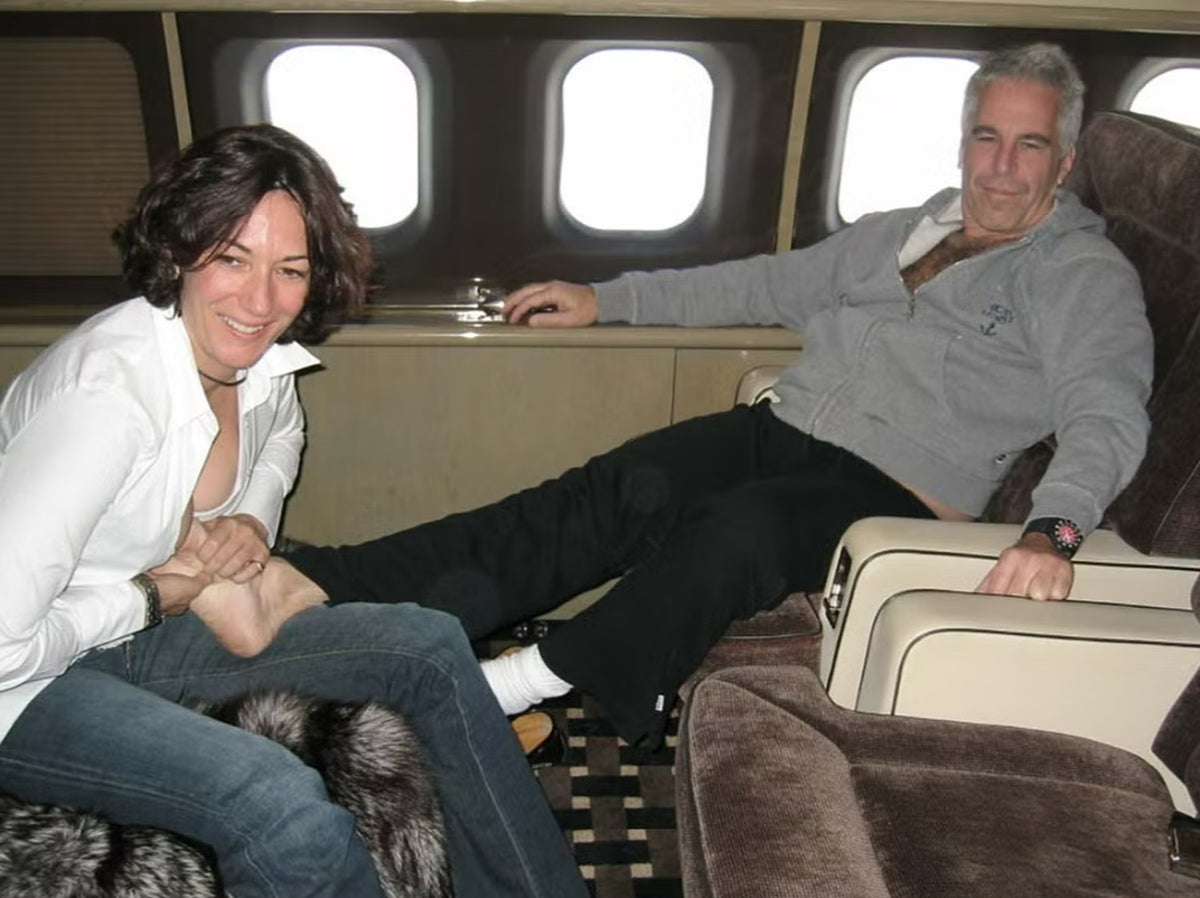

By the time her father died and she did meet Epstein in the early Nineties, Maxwell was, to those around her, growing increasingly sexualised and strange. At a cocktail party in New York, she strode up to the distinguished writer Jesse Kornbluth, a stranger, and within feet of his wife told him that “if you lost 10 pounds, I’d f*** you”. The startled man turned her down. Another acquaintance relays an equally disturbing anecdote. Asked how Maxwell kept her figure, the socialite replied that “Jeffrey likes his girls like that”, before going on to describe what she calls her “Nazi diet” – because you “never see pictures of fat concentration camp victims”. This from a woman whose grandparents, aunts and uncles were murdered in the Holocaust. Further gruesome accounts from the victims of Maxwell’s career as a sex trafficker of underage girls appear in the later episodes, and they are as shocking and painful as they should be.

Across the series, the stories are told clearly and calmly, while the archive is used effectively. Maxwell Senior was fond of home movies and the footage contains sharp insights. For example, we get glimpses of how Maxwell’s affectionate but manipulative relationship with her indulgent father developed early. There is a clip of a five-year-old Maxwell gleefully telling the camera how she’d nicked Daddy’s Christmas stocking so she could get more presents from Santa. On the make, even then.

So, if you think you know all there is to know about Ghislaine Maxwell, think again. It happened not so long ago; most of those involved are still alive, and some have remained silent up to now. We’ve not, then, heard the last of Maxwell, Epstein and their high-profile friends such as Prince Andrew. There will undoubtedly be more stories to follow – and more documentaries.