Canada’s inflation rate has started to ease up after peaking at 8.1 per cent last summer, but food and shelter prices are showing little sign of slowing down.

Increases in wages and earnings only partially make up for lost purchasing power. Those working in lower paying industries are less likely to see their wages rise.

Many Canadians are struggling and those on tighter budgets with less financial leeway are being hit especially hard. During fall 2022, one in four Canadians indicated they were finding it difficult to meet food, shelter and other necessary expenses, up from about one in five Canadians in summer 2021.

But these statistics are only part of the picture — Canada’s official poverty measure only focuses on income and ignores other important factors. This means millions of Canadians living in poverty are potentially going unseen and unheard.

Canada’s official poverty measure

Canada’s official poverty measure, the market-basket measure, is based on the cost of a specific basket of goods and services representing a modest, basic standard of living.

This basket is priced for a family of two adults and two children and takes local prices into account. When a family’s disposable income is less than that of the basket, they are income poor. For other living arrangements, there is a formula that adjusts the poverty threshold using the households’ size.

Yet, people’s individual circumstances are often more diverse than the market-basket measure can handle.

The market-basket measure ignores when people’s spending is higher because they have non-standard needs, such as a food allergy, student loan payments or they are paying above-average market rent for low-cost housing.

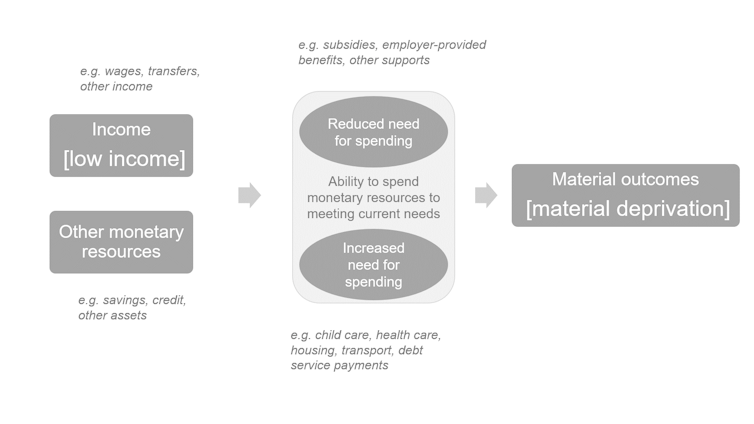

Higher expenditures to attain a basic standard of living explains why some people experience material deprivation while having an income above the poverty threshold.

Alternatively, access to resources other than income can explain why some people can avoid material deprivation despite having low income. This is because the market-basket measure disregards financial resources, such as savings or credit, that help finance an acceptable living standard, despite low income.

The market-basket measure also misses when people have access to subsidized goods and services, and work-related benefits like health benefits, which reduce out-of-pocket spending. Canada’s official poverty measure makes mistakes on both sides by excluding many who probably should be counted and including many that probably shouldn’t be.

A complementary poverty measure

I work with Food Banks Canada to collect data that provides a broader picture of poverty by focusing on a poverty measure called material deprivation. Material deprivation focuses on items that people with an acceptable living standard can afford, rather than just income.

We used opinion surveys and focus groups to identify socially perceived necessities for Canadians. An item is deemed a necessity when most respondents view it is necessary, or very necessary, for a decent standard of living.

Examples of these necessities include a pair of properly fitting shoes and at least one pair of winter boots; the ability to eat meat, fish or another protein equivalent every second day; and the ability to buy small gifts for family or friends once a year.

People are considered item deprived when they cannot possess a necessary item or engage in necessary activities due to a lack of money. People are considered materially deprived when they lack more items than the deprivation threshold.

There is no question that poverty is increasing right now. The market-basket measure numbers will reflect this, but they will nonetheless miss a key part of the poverty story.

Our material deprivation data will tell that story.

Routinely collecting such data as a complement to income poverty statistics makes sense. Not only in times of record inflation but always. Not only for charitable organizations but also for Canadian governments.

Policy that reduces poverty

Inaccurate poverty measurement tools not only skew our understanding of how much poverty there is and who is at risk, but also skew how policies contribute to reducing poverty.

Since he was elected in 2015, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said poverty reduction is a priority of the federal government. The government is now working towards reducing poverty by 50 per cent by 2030, as determined by the market-basket measure.

Knowledge that poverty is more widespread than what is deemed low-income implies that eligibility tests Canadians must meet to access government supports may have to be less stringent.

Likewise, such knowledge cautions against reducing income-tested government transfers like the Canada workers benefit, a refundable tax credit for low-income workers.

Moreover, comparisons between the effects of an income transfer like the Canada child benefit and subsidies like the Early Learning and Child Care system may be skewed. Income poverty measures automatically account for the income transfer, but they might underestimate or ignore the poverty reduction effect of subsidies.

Currently, we can only speculate about the scope and magnitude of such biases. But, given the relatively large gaps between low-income and materially deprived households, they could be substantive.

Geranda Notten works with Food Banks Canada to develop a Material Deprivation Index for Canada. The views in this article reflect those of the author only.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.