A distinctively American brand of ballet emerged in the 20th century, developed by George Balanchine, the longtime artistic leader of the New York City Ballet, and such notable other choreographers as Lew Christensen, Eugene Loring, Agnes de Mille and Jerome Robbins.

Sometimes overlooked is Gerald Arpino, a native New Yorker who co-founded the Joffrey Ballet with Robert Joffrey in 1956, and choreographed nearly 50 works for the company during his more than 50-year tenure with the company first as a dancer and later artistic director.

The Gerald Arpino Foundation is celebrating the 100th anniversary of the choreographer’s birth with a celebration highlighted by Sept. 23-24 performances featuring seven major American ballet companies, including the American Ballet Theatre, San Francisco Ballet and, of course, the Joffrey.

In addition, the Arpino Chicago Centennial Celebration will feature a reunion of some 150 past Joffrey dancers and staff with connections to Arpino and his works and a series of private events for them, including a repertory showcase and panel discussion.

“His place is very much at the center of the Joffrey,” Ashley Wheater, the company’s artistic director said of Arpino, “and he hasn’t been given his accolades, and so to have this anniversary is a really great way to honor him and celebrate him.”

Because most of Arpino’s ballets were created for the Joffrey and primarily performed by that company, they only began to receive broader exposure after his death in 2008, when his foundation pushed to make them available to other professional and academic companies.

“There is a resurgence in the love of his works, and we are very excited by that,” said Cameron Basden, a board member of the Arpino foundation who regularly stages his works across the country.

Arpino met Robert Joffrey while studying ballet with Mary Ann Wells when he was stationed with the Coast Guard in Seattle. The two established a school in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1953 and co-founded the Joffrey Ballet three years later. He was the company’s lead dancer until an injury sidelined him in 1963.

By 1965, Arpino had choreographed five works for the company and became its co-director and resident choreographer, helping to give the Joffrey its signature look. When Robert Joffrey died in 1988, Arpino took over as artistic director, a position he held until 2007, a year before his death.

In significant part through Arpino’s efforts, the Joffrey became one of this country’s best-known companies, devoting itself to touring for much of its history. But because of the profusion of major dance companies in New York, the company began to find it was not getting the financial support it needed.

So, in 1995, Arpino made the momentous decision to move it to the Windy City, which did not have a major ballet company.

“He really fought to bring the company to Chicago,” Wheater said, “and, what has happened is that Joffrey has its place here, and Chicago has been the lifesaver of the Joffrey.”

Erica Lynette Edwards, who was recently named executive director of Giordano Dance Chicago, joined the Joffrey Ballet at 19 in 2000 as an Arpino Apprentice, and worked with the company leader during the final seven years of his career.

During performances, she recalled that Arpino sat in a box on the right side of the theater.

“If you did something really well and it was time for your bow, you would hear ‘Bravo!’ coming from up there, and you were really happy. ‘OK, Mr. A recognized me. This is a big deal,’” Edwards said.

According to Basden, who danced with the company from 1979 to 1995 and later served as a rehearsal director and co-associate artistic director, Arpino was a true classicist but also a devotee of contemporary ballet.

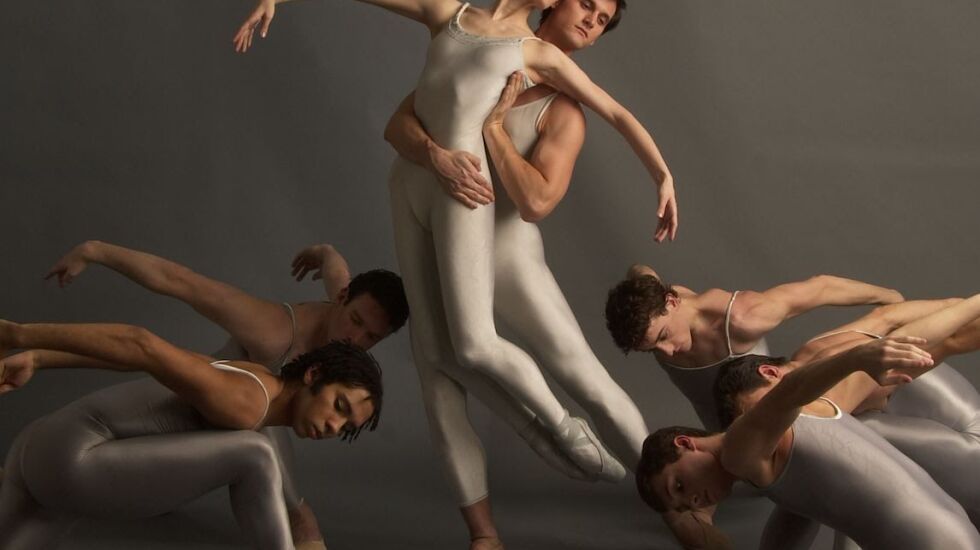

“So, in a sense, that makes his movement very American,” he said, “because it’s a blend of what we know as a dance. It’s speed, it’s moving along the floor as a modern dancer would, but with the elegance and technique a classical dancer would have.”

In a 2004 Sun-Times story documenting the Joffrey’s return to New York City for a series of performances, Arpino said of the company and his style: “My dancers are very self-correcting, and much freer than dancers were in the past. The secret is to let them discover their own artistry through me — not to impose anything on them. I turn the movement over to them and see what extra things they can bring to it.”

Although Arpino did choreograph more serious, sometimes socially relevant pieces like “I/DNA” (2003), which dealt with the death penalty, he is best remembered for his lighter, more upbeat works. Basden and Wheater used words like “exuberant,” “dynamic” and “energetic” to describe his style.

“The type of movement quality that he had, the use of the torso, the extreme lines, the speed— dancers really love to dance them but almost as important, audiences love to see them,” Basden said of Arpino’s works.

The two Arpino Centennial programs will contain nine of his best-known works, including some that have not been presented anywhere for more than decade. “Valentine” (1971), for example, was last performed in 2007, and “Reflections” (1971) has not been seen since 2010.

“For the people who remember, of course, it’s a trip down memory lane,” Wheater said. “For people who have never seen Jerry’s work, it gives them a huge variety of what the man created. And I think it will be very interesting to see what these other companies, which didn’t have a direct attachment to Jerry or the Joffrey, will bring to his work.”

One of Arpino’s most performed pieces is “Light Rain” (1981), which Ballet West will present on Sept. 24. Basden described it as a “dancer-friendly, audience-friendly, exuberant piece,” and Edwards called it a “rite of passage” for Joffrey dancers.

The Joffrey will present two works during the centennial celebration: “Suite Saint-Saëns” (1978), a frolicsome, neo-classical work revived in 2022 in anticipation of the anniversary, and “Round of Angels” (1983), which the company has brought back to its repertory for this event.

“’Saint-Saëns’ is one of his signature works,” Wheater said, “and the Joffrey has always danced ‘Saint-Saëns.’”

He was performing that work with the Australian Ballet, when Arpino and Robert Joffrey invited him to join the Joffrey Ballet in 1985.

“It’s a joyous, beautiful piece, and it’s a great showcase for the company,” he said.

Basden hopes the centennial celebration and the buzz it generates will bring renewed attention to Arpino and lead to more performances of his work.

“I think we all hope,” she said, “that people will once again honor and celebrate Arpino and his legacy.”