The first line of Olivia Harrison's book of poetry captures a feeling universal to everyone who has lost a loved one. “All I wanted was another spring,” she writes. “Was it so much to ask?”

Through the verses that follow that question, the widow of former Beatle George Harrison opens up about her husband, and about grieving after he died of lung cancer at the age of 58 on Nov. 29, 2001.

Twenty poems for 20 years, a number that's not a coincidence.

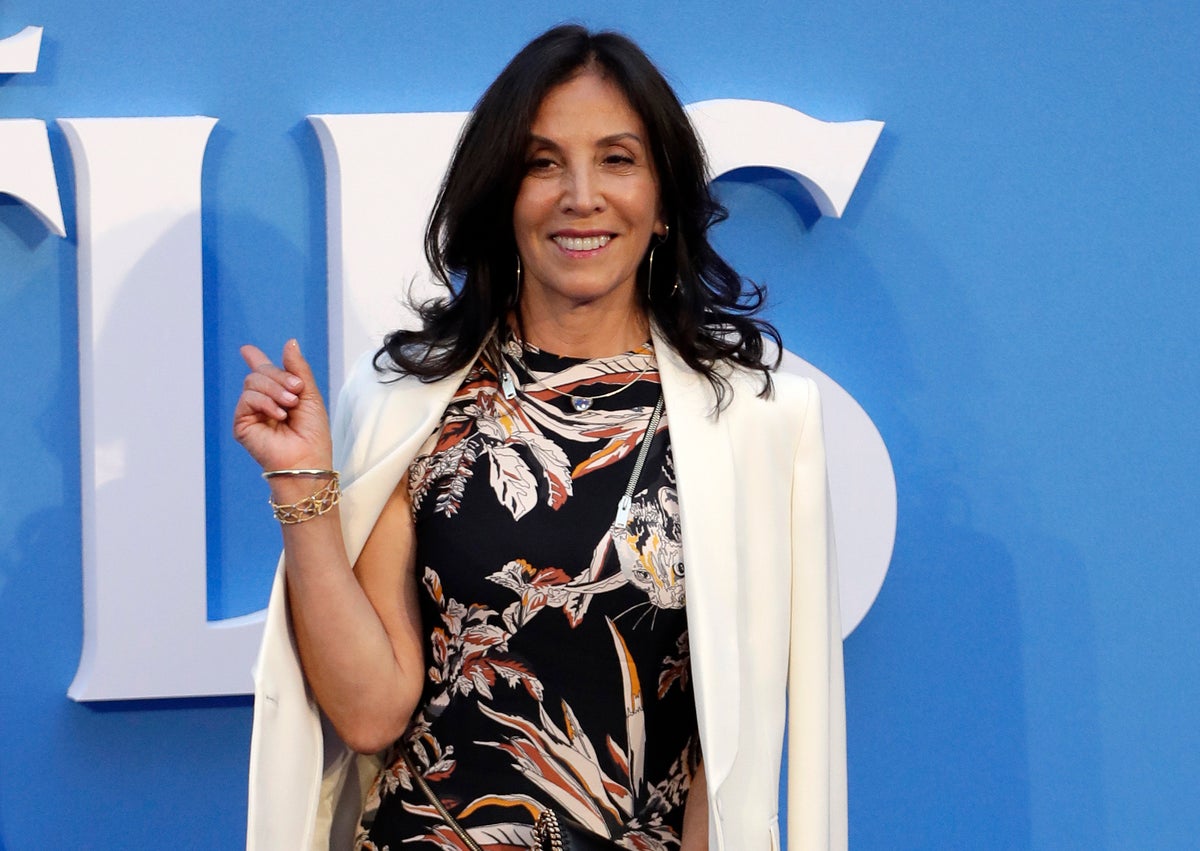

“Came the Lightening,” a collection published Tuesday, is a first for the 74-year-old Harrison, and a surprise. She has meticulously curated George's work with the help of their son, Dhani, but has otherwise maintained the privacy the couple kept throughout their marriage.

She was inspired to write by reading Edna St. Vincent Millay's work about a “wound that never heals,” and her own line about wanting another spring was a turning point. She changed her mind after initially deciding not to release it publicly.

“It was because he was a good guy,” she said in an interview with The Associated Press. “A good guy. And I thought, ‘I want people to know ... these things.’ So many people think they know who George is, I thought that he deserves this, from me, to let people know something a little more personal.”

She writes about the mundane moments of a marriage that become more special when they can't be repeated — the late-night dances to a jukebox in their living room, how her cold feet sought the warmth of his under the covers on a winter night.

George Harrison met the former Olivia Arias in the 1970s when she worked at his record company in Los Angeles. One poem recalls her nervousness in first welcoming him to her Mexican immigrant parents’ humble home. “He said, ‘it’s a mansion compared to my youth,’” she wrote.

She remembers him welcoming her into his Friar Park estate west of London for the first time with the gentle words, “Olivia, welcome home.”

They drove up in “John and Yoko's long white car." It was another hint that she wasn't just marrying anyone, along with her description of the day “the legendary Slowhand dropped in with the ex-Mrs.”

That would be Eric Clapton, with George's ex-wife Patti.

Awkward!

“It seemed to be this love triangle legend,” Harrison said. “I thought I would try to get it over with in three verses.”

Her husband never talked publicly about losing his first wife to Clapton, and Harrison's poem indicates it didn't go well. “Predictable exchanges and yes, they ended badly,” she wrote.

Harrison also writes, at some length, about the harrowing night of Dec. 30, 1999, when a disturbed man with a knife broke into Friar Park. She recalled pleading with George to stay hidden in the bedroom but instead he went down to confront him and was stabbed in the ensuing struggle. Olivia attacked the intruder with a fireplace poker and, against odds, they both survived.

“I wouldn't say it was a defining moment, but it was such a profound experience that I still can't believe,” she said. “George nearly died and you think, no, he's not going to die like that. He was a very defiant person in that sense — I'm not going to die like that. He was thinking that at the time, actually."

Nineteen years earlier, she had taken the middle-of-the-night phone call that John Lennon had died, and they huddled under their blankets for hours.

Even though George died not quite two years after the Friar Park attack, she considered it "a victory, not a loss.

“It was a victory because he went out on his own terms in the way that he wanted to,” she said. “It was something that he regretted that John Lennon didn't have the chance to do.”

Harrison writes tenderly about the day her husband died: “I wanted you to leave without any impediments of care, to float away like you always imagined and prepared. I couldn't help myself and nuzzled your ear, and whispered final words to leave you with my sound.”

Their son was 23 when George died. Harrison said she's constantly surprised to hear him talk about things she didn't know his dad had told him.

“Whether it was something for history's sake, or a mantra, or some lesson, I thought, he didn't wait until (Dhani) was 30 or 40,” she said. “That's a real lesson, too. Why do we hold back? Why are we so constrained by time? George didn't live like that. Maybe he was prescient. Maybe he knew.”

In the book, she also writes about the final visits of Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr to say goodbye to their former Beatles mate.

Now, she and Dhani sit at the boardroom table with McCartney, Starr and Yoko Ono when Beatles business is discussed. It's in many ways an ongoing venture, like with last year's Peter Jackson-produced “Get Back” project.

“Dhani and I are really there to look after George's legacy,” she said. “On some things, we're more opinionated. But on other things, I'm like, ‘it’s their music, it's their images ... they know what they want to hear and see. It's great to shepherd and provide George's material and help them in any way we can.”

Besides, she said, it's a lot of fun.

It wasn't until the anthology project in the 1990s that George became more comfortable with the Beatles legacy, she said.

“He said, ‘I guess it's not going away.' I said it's not. He was so funny. I said, no, it's not and he said, ‘Good, maybe I’ll get some respect around here,'” she said with a laugh.

Harrison still lives in the Friar Park estate. She's too old to move, she said, and too much stuff is accumulated. She and her husband were both avid gardeners, and one hint about why she stays comes in a poem that talks about the trees there: “My constant source of comfort, my oldest, tallest friends,” she writes.

She also writes of “one more meeting, I've written the scene, where I get off my chest one final thing."

What might that meeting be like?

“It would probably be in the garden,” she said. “Just sitting in the garden, (where he would say) ‘aren’t you glad I planted that tree over there?'”