Following the raid on the al-Shifa hospital in Gaza by units of the Israel Defence Forces on October 15, the IDF claims to have uncovered evidence of tunnels underneath the hospital. A video released on November 19 showed a tunnel running under the al-Shifa medical complex at a depth of ten metres, running 55 metres along to what IDF sources said was a blast-proof door.

The tunnel’s entrance was reportedly exposed when a booby-trapped truck in a garage on the hospital’s grounds was exploded. The IDF claims this is evidence that there was a command and control centre beneath the hospital complex.

The video is yet to be independently verified. Given the crucial importance that such evidence will play in justifying a raid on a premises that is protected under the rules of war, such verification will be critical.

There were also claims published several days before the tunnels were reportedly uncovered referencing a 2014 article which asserted that the complex had been built in 1983 when Israel was in control of Gaza. Again, this claim has not been investigated. Forensic investigation of the site and all records pertaining to construction work there will be of huge importance.

As forensic investigators, we have extensive experience in below-ground exploration, including locating mass graves in Colombia, where – for ethical reasons – it’s not possible to just go in and start digging. So it’s necessary to use a range of technologies above ground to gather sufficient evidence to excavate in what might be a sensitive area.

Every site is unique, but investigators commonly use a phased approach. This may involve initial analysis of remote sensing satellite and aerial data that includes photographs, near-infrared imaging datasets, historical and modern site maps and other available information. Geological maps and subsurface models may be combined with knowledge of the technology and resources available to those excavating tunnels, shafts and chambers.

The terrain under the Gaza Strip comprises rocks and sediments that become thicker from the east of the Red Sea to the Mediterranean. This makes the area suitable for tunnel construction, although there are still hazards in the form of faults that displace layers of rock and allow water to get into underground spaces (especially close to the sea).

Hi-tech tunnel hunters

This pattern of surface and deep geology would then identify areas for near-surface geophysics site surveys that may use active technology to pulse signals and measure the responses before mechanical drilling or excavation to identify areas or objects of interest. Even relatively deep targets such as mineshafts and sinkholes have been located using this approach.

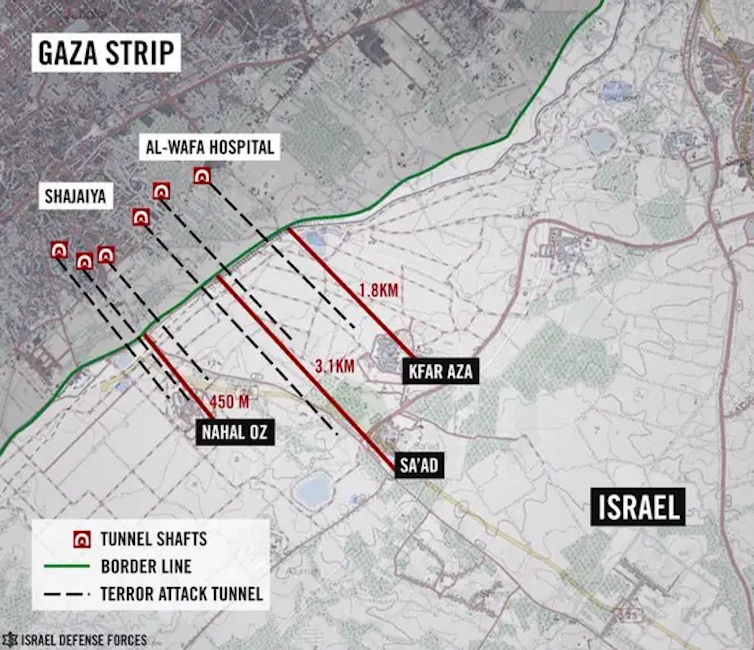

Specialised seismic and ground penetrating radar (GPR) geophysical surveys have been used to detect tunnels in Gaza. But this gets progressively more difficult the deeper they are – some in the Gaza Strip are reportedly as deep as 70m.

To detect tunnels and bunkers below human-made structures, remote sensing methods commonly use instruments on satellites, unmanned aerial vehicles and aircraft to provide datasets to analyse. Once interpreted, these can pick up disturbed versus undisturbed soil and pinpoint areas of high gases such as methane or heat emitters. But these would have to be very sensitive and interpretation is typically very difficult for deeply buried targets. Entrances would be key to locate here – that is apparently the case in the al-Shifa hospital.

Micro-gravity methods that could detect missing mass, such as tunnels and bunkers, have been used within buildings. They have been used, for example, to detect burial sites below church floors and Egyptian pyramid tombs as this technique is not depth limited. Airborne gravity gradient surveys, that use what is called microgravitmetry to detect targets, show potential, but may not have the required resolution to detect bunkers at such depths in this case.

Both the microgravity surveys, data processing and numerical modelling are used to calibrate results to estimate what is causing the data signal. It’s then important to accurately digitally remove the effect of the above-ground extra mass of buildings to then look at what’s underneath. The cost of this can be significant in terms of time and resources.

In the past, high-resolution GPR surveys have detected unmarked cellars beneath commercial shop floors and hidden pipebombs and detonators behind shower tiles in Northern Ireland. But GPR is depth-limited to a few metres in most cases, with metal reinforcements causing problems in the data.

Listen up

An alternative approach is possibly the oldest: listening for sounds from underground. From listening to tunnels being dug (as they did on the western front during the first world war), or detecting vibrational energy from sound sources, most especially sound produced from tunnels being dug or by people themselves, walking, talking and making noise.

This too has severe constraints. You are effectively “listening” to what is going on under sometimes metres of ground – the vibrations – and it’s often difficult to tell the difference between the sound of low-energy seismic movements and human-made sources. It also takes time to process and potentially model the data too.

There are a range of intrusive investigation techniques. These include sinking slim borehole systems and inspection cameras on cables. But they are slower digging methods – particularly when they involve drilling through bedrock and reinforced concrete.

The final stage is visual inspection. Verifying the function of the tunnel, shaft or chamber requires examination of the equipment contained there. Judgments have also got to be made about whether the structure was physically able to be used for a military purpose – whether that’s the storage of weapons, as a bunker for troops to hide or for a full-blown command and control centre with all the equipment, power sources and connectivity that would require.

The only true way to be definitive about the presence of subsurface structures in Gaza is by physical investigation, which will take significant time and effort, especially with the reported depths below ground level involved.

Jamie Pringle receives funding from the HLF, the Nuffield Foundation, Royal Society, NERC, EPSRC and EU Horizon2020. He is affiliated with the Geological Society of London. Jamie works for Keele University.

Alastair Ruffell receives funding from RCUK (NERC and EPSRC). He is affiliated with the Queen's University, Belfast, the Geological Society of London and International Union of Geosciences

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.