The last time I saw Gabrielle Carey, who died this week, aged 64, was a couple of weeks ago in Sydney. I’d texted that I was coming to Sydney for the weekend, and she texted back to say she was meeting “a couple of Joyceans” for a morning walk in Lavender Bay and would I like to join them?

“Joyceans” was an important code-word for Gabrielle. She is still best known as the coauthor, with Kathy Lette, of Puberty Blues (1979), a book she wrote as a teenager. The novel, a gritty account of the brutally sexist surf culture of Sydney’s southern beaches, was a smash hit, as was the film adaptation directed by Bruce Beresford two years later. For Gabrielle, it was an early fame she would never entirely succeed in escaping.

But for many of those who knew Gabrielle later in life, she was, among many other things, a “Joycean”, and more particularly, a “Wakean”.

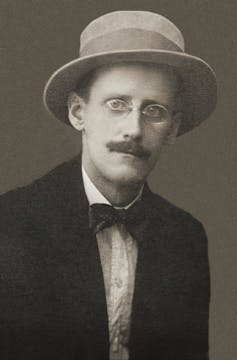

She was a lifelong scholar of James Joyce, the towering Irish modernist writer whose last book, Finnegans Wake – a 628-page novel written in an invented language mixing the most arcane English vocabulary with more than 60 other languages in an almost unreadable riot of wordplay – is justly notorious as the most fiendishly difficult book ever written. As Gabrielle writes:

Wake language is a language of its own. Once you get the hang of it, Wakean words become a kind of code to share. If you’re finding it hard to make a decision, you can say you’re in “twinsome twominds” and your fellow Wakeans will understand. Or if you have some gossip, you can say “I’ve got a seeklet to sell.” Or if you just want to exclaim, you can invert a cliche: “O for a fresh of breath air!” Or if someone asks why you’re doing something, you can respond, “Just for the halibut.”

Gabrielle was an internationally respected expert on the Wake. She was in regular correspondence with the leading scholars; she was the author of numerous acclaimed essays on Joyce.

She was a performer, along with a number of other Wakean women, in the “Prankqueans”, a musical troupe named after one of the Wake’s characters and dedicated to performing the opera and popular song that is so richly studded throughout Joyce’s writing. And she was the leading light of not one, but two Finnegans Wake reading groups.

Her last book, currently in press, is simply titled James Joyce: A Life. But, by contrast with Joyce, her own style was often so modest and accessible and democratic, albeit with a fierce and fearless honesty, that it is easy to underestimate the formidable intellect at work behind her writing.

Authors were ‘living beings’ for her

After Puberty Blues, Gabrielle Carey would go on to publish nine other books, spanning fiction, biography and memoir, as well as numerous essays and newspaper pieces.

Probably her most distinctive contribution is a series of books that defy categorisation: studies of other writers that combine literary biography and autobiography, archival work and personal memoir, scholarly analysis and deeply personal reflection.

Authors were never abstract presences for her, they were living beings who breathed through their books, and it was possible to have a relationship with them every bit as passionate and dangerous as a relationship with a living human being.

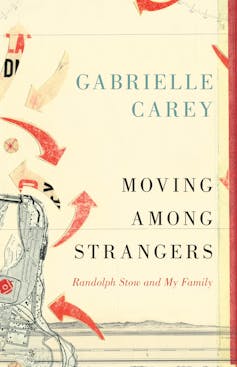

The first of these was Moving among Strangers: Randolph Stow and my Family, a book which won the Prime Minister’s Award for Non-Fiction in 2013.

Her previous book, Waiting Room (2009), was a searching and fearless memoir of her distant and estranged mother’s terminal illness with a brain tumour, in which she briefly mentioned her mother had been friends with the reclusive Western Australian writer Randolph Stow.

In Moving among Strangers, she tells how she had written to Stow during her mother’s last days, and that he, a deeply private man, had not only responded warmly with reminiscences of familiar family stories, but had hinted at a side of her mother’s early life and personality that Gabrielle had never known existed. When she pressed him for more, he fell silent, and within a year, he had died.

Moving among Strangers tells the story of a daughter’s search to find out more about her mother and the younger self her daughter never saw or knew. It’s also a study of an enigmatic writer who was once internationally acclaimed, but who has now almost disappeared from Australian literary history. And it’s a searching meditation on the intense relationships that can form between intensely private people.

Falling out of Love with Ivan Southall (2018), as the title suggests, is a similar combination of literary biography and memoir. I remember, like Gabrielle, devouring Southall’s books as a child. And Southall, like Stow, is a writer who has almost disappeared from literary history. Gabrielle’s book, part literary biography, part personal memoir, recounts how her attempts to find out more about the writer that she fell in love with as a child reveal a person far different from her once-adored hero.

The third of these, Only Happiness Here: in Search of Elizabeth von Arnim (2020), was completed during Gabrielle’s fellowship in Canberra. Written in deceptively simple prose, the book deftly layers several different genres and styles and pursues a complex sequence of interlocking arguments.

On one level, it’s a literary biography of another writer who has been unjustly neglected. Born in Kirribilli in 1866 to the distinguished Beauchamp family (Katherine Mansfield was a cousin), Elizabeth married an Austrian count and moved to his family’s landed estate in Nassenheide, where along with raising his children and running his business affairs, she established a famous rose garden.

Her anonymously published book Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898) was a huge hit, a semi-autobiographical account of the making of her garden as well as a satirical portrait of the deeply conservative and sternly patriarchal Junker aristocratic society.

Von Arnim went on publish more than 20 books, mostly fiction, that were both critically acclaimed and commercially successful enough to support her and her financially incompetent husband in the style appropriate to their milieu.

She was friends with novelists E.M. Forster and Hugh Walpole, and had an affair with H.G. Wells. Her second husband was philosopher Bertrand Russell’s elder brother, and she wrote a witty pseudo-autobiography in the form of a memoir of her favourite dogs, in which her glittery social circle can be glimpsed only in the background.

“Only Happiness Here”, the motto Elizabeth put over the entrance to the Swiss chalet where she entertained her friends, is a funny and moving study of von Arnim’s life and work. But it’s also a kind of treatise on the art of happiness: a topic that, as Gabrielle notes early in the book, presents all sorts of moral and aesthetic perils for the writer, including the risk of being sententious and boring.

From von Arnim’s writing, Gabrielle extracts nine buoyant “Principles of Happiness” that form the running motif of the book and guide its exploration of von Arnim’s troubled life, her enigmatic personality and her unjustly neglected fiction.

Gabrielle also makes the interesting claim that perhaps the reason that the literary history of Modernism has forgotten about von Arnim is that “Modernism didn’t believe in happiness”.

Read more: The case for Randolph Stow's To the Islands

‘She works for James Joyce’

Gabrielle’s final book, James Joyce: A Life, is currently in press. As she quipped, it was her “fourth biography and the first about a writer who is still famous”. It’s a brief, deft portrait of a complex subject, focused not just on the irritably narcissistic Joyce, but also on the women who supported him and made his maniacal dedication to his own genius possible.

In particular: Nora Barnacle, his partner and later wife; Harriet Shaw Weaver, his admirably patient and deep-pocketed patron; and Sylvia Beach, his courageous and indefatigable publisher.

Two of Gabrielle’s acclaimed essays, Waking up with James Joyce and Breaking up with James Joyce, give an indication of the conflicted relationship she maintained with this writer who inspired and infuriated her throughout her life.

Breaking up with James Joyce, listed as a Notable Essay in Best American Essays 2019, tells an anecdote of how, when her nine-year-old son was asked “And what does your mother do?”, he replied without hesitation: “She works for James Joyce.”

In Gabrielle’s typically witty but revelatory style, her essay begins with a letter to “Jim” saying that, after more than 40 years of selfless dedication to his work, she’s had enough: “It’s over”. But a little later she worries she’ll lose her resolve, confessing, “For some reason, I need him”.

Gabrielle’s lifelong love of Joyce was undoubtedly a source of joy as well as anguish, and perhaps the most powerful way she communicated this joy was through her creation of that tiny, unique and irreplaceable institution, the Finnegans Wake reading group.

The Wake became the prompt and the pretext of a very special kind of conversation: a sharing of knowledge, guesswork, imagination, fancy, irreverence and reverence. It is in this way that I and my fellow Wakeans got to know her, and that is how we will remember her.

Read more: The amateur’s age of unriddling: Finnegans Wake on stage

Reading groups ‘like jam sessions’

The first of these, based in Sydney, met on the last Sunday of the month, often around Gabrielle’s table, for 17 years: the length of time it took Joyce to write the novel. They would gather over food and wine and take the Wake a page and a line and a word at a time.

Someone would read aloud, and everyone would chip in with suggestions and ideas, deciphering Joyce’s bawdy double entendres and cryptic allusions to everything from nursery rhymes to theological disputes. Each would be encouraged to draw on whatever unique knowledge they could bring to the table, from etymology to entomology (literally; there are passages in the Wake incomprehensible to anyone but a specialist on insects).

If they got really stuck, they’d turn to Fweet, an online guide to the Wake with more than 90,000 explanatory annotations. It is testament to the magnetic power of Joyce’s text, and Gabrielle’s passion to share the joy of reading it with others, that when they finished it, after a short pause, they turned around and started again – just like the Wake itself, which begins in the middle of a sentence and ends with the first half of that final-first sentence: “A way a lone a last a loved a long the.”

The second Finnegans Wake group she set up was in Canberra, in 2019, when she came to the Australian National University as a recipient of the prestigious H.C. Coombs Creative Arts Fellowship.

Her Canberra Wakeans formed the “Museyroom Players”, and produced with her a series of events over the next few years combining talks, readings, performances, songs, music and media art we termed a “Funferal”: a word from the Wake that combines funeral and fun-for-all, with just a hint of the feral.

Gabrielle’s copy of the Wake was a thing to behold: held together by a several loops of pink ribbon, every page was covered in tiny pencilled annotations. If somebody came up with a new insight, she’d painstaking note it in even tinier pencil between the existing marginalia.

Once, in response to some abstruse question, she fished out from its inside cover a letter from Danis Rose, perhaps the world’s foremost scholar on the Wake, and the editor of the astonishing website the James Joyce Digital Archive.

But Gabrielle’s scholarship was not that of the peevish disputes over typographical minutiae that characterised the so-called Joyce Wars. Her approach to the Wake was always more about the shared joy of the present moment than the potential for some future authoritative statement.

Indeed, Gabrielle’s “Joyceans” are not just writers and literary scholars, but schoolteachers and musicians, professors of medicine and security guards. She had a genuine belief – and could prove it – that Finnegans Wake is a book for everyone. Her reading groups were more like jam sessions than scholarly seminars.

The art of living well

Gabrielle was a teacher of the art of living well. She dressed with consummate style: elegant, understated, interesting fabrics, beautiful tailoring.

When she moved to chilly Canberra (a city which she had the unusual distinction of loving unreservedly) she immediately bought thick stockings and thermal vests so she didn’t have to get around in the shapeless puffer jackets that most Canberrans rely on to stay warm.

She was a connoisseur of “interesting” hotels and restaurants, and in January 2023 conspired to bring her Canberra and Sydney Wakeans together at the Robertson Hotel in the Southern Highlands: three storeys of antiquated grandeur in wood panelling and stained glass and sweeping staircases, surrounded by hydrangea-bordered lawns and creeping mists as dusk set in.

Every evening, no matter where you were, Gabrielle would always step outside for a few minutes to watch the sun set. A keen gardener, she made tiny pots of fabulously precious jam, that she playfully labelled “Jams Joyce”, from rose-petals harvested from her garden.

I remember her once being delighted by something my daughter had said. When she was four or five, and her grandmother was taking her out to buy shoes, my daughter patiently explained : “Shoes that aren’t glittery hurt my feet”. This was Gabrielle too.

She brought style and charm and beauty and grace to everything she did and everyone she met, though she was quickly discriminating in her judgement about people and places and tasks that she feared would be a drudgery. She knew, with a firm determination, that there is a glorious expenditure of pain in beauty, and that happiness requires a wastefulness that is heedless of saving something for a better day.

A person of diminutive stature and, I think, a shyness beneath her warmth and grace, she was capable of being imposing when she needed to be. Once, trying to read a passage from the Wake in a dimly lit bar, she commanded loudly, without looking up, “Waiter, I can’t read in here! Bring me a torch!”, which the waiter, promptly, did. And if something was not right – if a teapot was not scalded before the tea was made – Gabrielle would send it back, and back again, or go into the kitchen and teach them how to do it properly.

She was also a generous bestower of praise and encouragement, but it was never facile or unearned; she had a gift for recognising in people what was best in them and drawing it out.

When I met up with Gabrielle and her Joyceans that weekend in Sydney, we went for a walk in Wendy’s Secret Garden, the garden that Wendy Whiteley, during a period of intense grieving for her husband, the painter Brett Whiteley, created on the strip of landfill alongside the railway line below their Milson’s Point house.

When it began to rain, we sat under a shelter at the bottom of the garden, shouting to be heard above the sound of the rain and the clanking of hammers and screeching of angle grinders from the railway work going on a few metres away – but invisible behind the dense foliage. Every now and then the glow of an arc welder would flash through the leaves like lava breaking through rocks. When the rain stopped and we made our way back up the slope to the huge spreading Moreton Bay fig on the terrace overlooking the harbour, Gabrielle made the apology of a hostess: “I’m so sorry about the noise, it’s usually much quieter here”.

The four of us went around the corner to her friend’s place and had a bite to eat and another Joycean treat, a nip of “Aramo di Erbe”, the bitter citrus liqueur made in Trieste, Italy, where Joyce spent much of his writing life. Gabrielle and I then caught the train into the city, exchanging recommendations of books to read and films to see, and when I got off at Wynyard, we embraced briefly, as you must when the train doors are closing.

When I came out of Wynyard Station, Sydney was in full torrential downpour. Instead of going to the Art Gallery of New South Wales as I’d planned, I went to the nearby Museum of Contemporary Art at Circular Quay.

There I came across the beautiful, poignant work by Simryn Gill, “Maria’s Garden” (2021), a series of life-sized ink-on-paper transfer prints of each of the plants from her neighbour Maria’s garden, after Maria had died and the garden was going to be demolished by property developers.

I immediately thought “Gabrielle will love this”, and so began to see the work through her eyes, registering details I could talk about with her the next time we met. Her passion for things had that quality of enlarging your experience, making the world a richer and more beautiful place.

In her last year, Gabrielle had been taking classes in the art of bookbinding, a creative outlet to add to gardening and rose-petal jam, not to mention writing.

It was uncannily appropriate, for so much of Gabrielle’s writing had been about exploring how a writer can become bound to – and bound by – the books and writers she loves.

But in addition, her writerly life was also an exploration of how books can bind readers together, bringing them closer to each other in a shared love of the beauty and power and strangeness of words.

Russell Smith does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.