Here’s something scientists want you to know: Your microbiome is complex. Sure, we’ve come a long way in our understanding of how the ecosystem of microorganisms — bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other teeny tiny life forms — affects health and spurs disease when the balance between good and bad microbes is tipped. But there’s still lots we don’t know, like how exactly do microbes chilling in the gut influence tissues and organs far away such as the heart or brain?

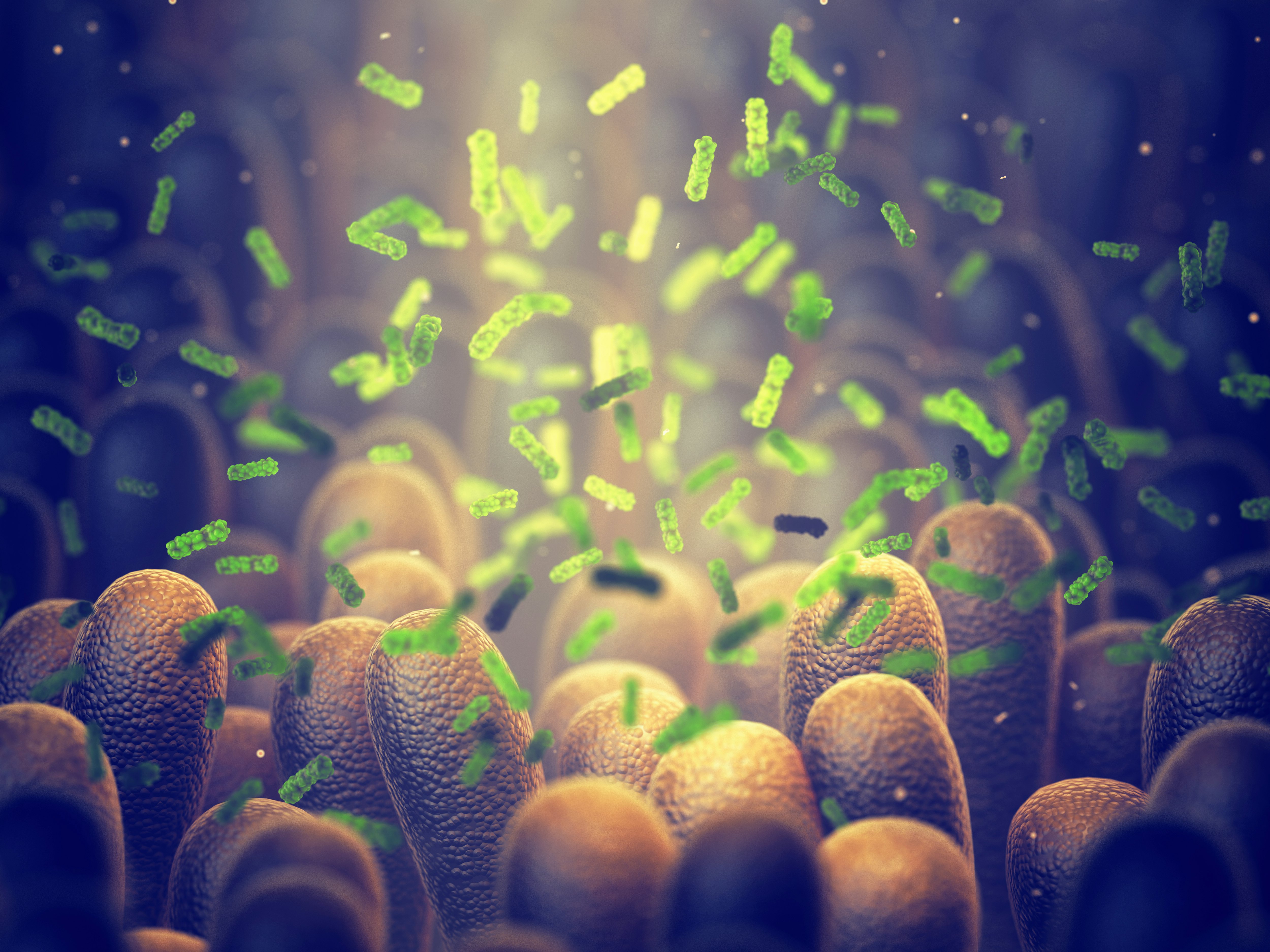

There’s a thought that some bacteria have the ability to pull a Homer Simpson and slip through the gut barrier to get to the rest of the body. According to a study published Wednesday in the journal Science Translational Medicine, scientists are now finding evidence of this thanks to a method using antibodies to pick up and identify these microbial escapees in serum, the protein-rich liquid portion of blood. This new method may help close the gap between gut bacteria and the immune system, uncovering the myriad of switches these microbes flip whether to benefit or harm their unsuspecting human hosts.

Here’s the background — When we talk about the microbiome, quite often we draw a line between good, healthy bacteria and bad, disease-causing bacteria. But that characterization isn’t so black-and-white, Ivan Vujkovic-Cvijin, the lead author of the new study and assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Science and Gastroenterology at Cedars-Sinai, tells Inverse.

“The more we learn about [the microbiome], the more we realize that it’s really context-specific, that certain bacteria in some contexts, certain genetic susceptibilities, or [possibly] certain diets, maybe worse than others for a given disease,” he says. In other words, a species of bacteria can be good or bad depending on the situation or environment it's in.

“But on the other hand, they also may protect from another disease, so it’s an immensely complex situation.”

How they did it — To get down to the bottom of that complexity, Vujkovic-Cvijin and his team wanted to better understand and identify gut bacteria that seemed to rile up the immune system despite being considered one of the good guys. Doing that can be super challenging though. Current tools to track down microbes that have bypassed the gut are very limited but not impossible if you use antibodies — Y-shaped bloodhounds of the immune system produced in response to foreign invaders.

When there is a foreign invader in your gut, your body produces a type of antibody called IgG, which binds to the bad guy and tags them for destruction. Vujkovic-Cvijin and his colleagues used this antibody to design a method that lets them catch free-roaming gut bacteria provoking the immune system.

Looking at blood and fecal samples from people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), healthy volunteers, and healthy mice infected with Toxoplasma gondii (a parasite known to breach the gut), “we found supporting evidence that systemic IgG [from blood serum] would help us identify those bacteria crossing the border,” says Vujkovic-Cvijin.

Putting their new detection tool to the test, the researchers found that among people with IBD (which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), gut bacteria confirmed to be routine jailbreakers were triggering the immune system and sending levels of the IgG antibody through the roof. Some of these bacteria include members of the Collinsella family (believed to be involved in Crohn’s disease) and the Lachnospiraceae family, a group with a complicated role in gut health with some studies suggesting an abundance of them may be associated with aging whereas other studies show Lachnospiraceae can be beneficial.

Why this matters — “There’s so much evidence that immune responses to the gut microbiome are important for a variety of diseases,” explains Vujkovic-Cvijin, such as obesity, liver disease, cancer, to even some neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis, and stroke.

Because there is still much we don’t know about what sort of chemicals each denizen of the microbiome produces (not to mention who exactly all these microorganisms are), we have an incomplete understanding of all the mechanisms driving or preventing any one disease. This also means we can’t fully predict whether someone’s microbiome puts their health and wellness at risk or worsens a pre-existing condition.

“I think some very promising application of this research might be in the prediction of disease course, of diagnosis, of possible subsetting individuals for treatment [like in] selecting some populating with a disease that might respond better to a given treatment,” says Vujkovic-Cvijin.

Digging into the details — While this study focuses on bacteria, they aren’t the only inhabitants of the gut influencing the immune system. We’ve got fungi like Candida albicans and Malassezia restricta — both implicated in IBD — but also beneficial fungi like probiotic yeast Saccharomyces boulardii.

“Fungi are a component of the microbiome that are known to have a strong impact on the immune system,” says Vujkovic-Cvijin, “[but] we were unable to capture immune responses to specific fungi.”

Another caveat to this research is that IgG is a huge family with different subclasses that may be more important than others in tracking down errant gut microbes. Since the Cedars-Sinai researchers only looked at IgG broadly not specifically, they weren’t able to suss out whether any one of the four subtypes is more critical than the others.

What’s next — Next up, Vujkovic-Cvijin and his team are planning to include the fungal microbiome (aka the “mycobiome”) in upcoming studies, as well as figuring out exactly how some gut bacteria are able to jailbreak the gastrointestinal tract.

They also hope their findings will make it easier for scientists in the microbiome research community to pioneer practical applications like diagnostic testing and therapeutic options, particularly in inflammatory bowel disease, the latter of which Cedars-Sinai researchers are currently pursuing.

“I really believe in the microbiome’s capacity to impact human health and that’s all that I care about,” says Vujkovic-Cvijin.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to clarify that IgG is the antibody the researchers used to catch free-roaming gut bacteria. It has also been updated to reflect the fact that Toxoplasma gondii is a parasite, not a bacteria.