Court Theatre’s stark, riveting production of “The Island” begins with the sound of waves crashing — almost lulling cadences that evoke beauty and tranquility. But when the lights come up in director Gabrielle Randle-Bent’s staging, there’s no water to be seen. We’re in a scorched world of burnt umber sand and concrete slabs bleached to bone. This is Robben Island, the South African prison where Nelson Mandela spent 18 of his 27 years incarcerated. Here, the ocean was repurposed as a prison wall.

In the first, wordless scene of the 100-minute, two-man drama by Athol Fugard, John Kani and Winston Ntshona, we see two prisoners going through the torturous machinations of the day.

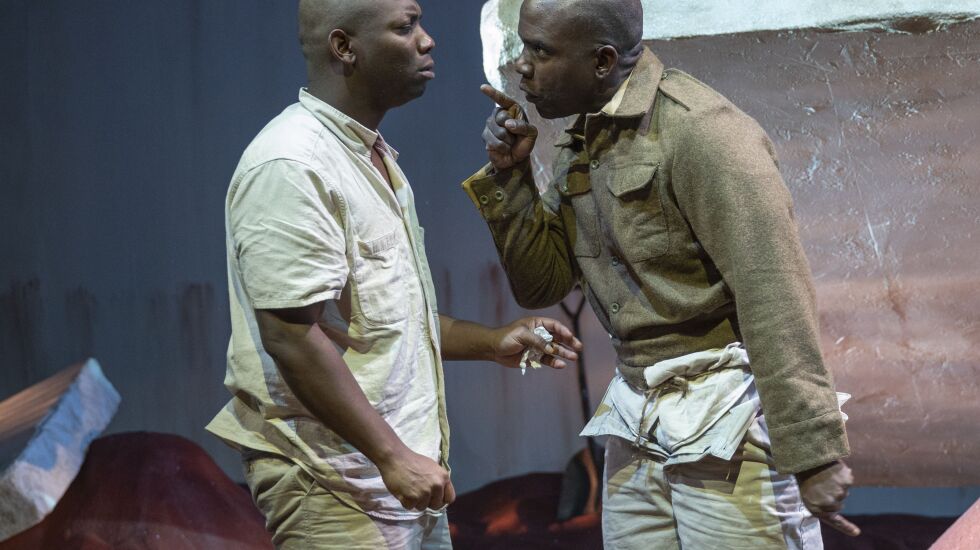

The ear-piercing blast of a whistle sets the pace as shackled convicts Winston (Ronald L. Conner) and John (Kai Ealy) are forced to run in circles and engage in pointless hard labor, shoveling sand from one place to another, sometimes carrying it in their fists. When the shackles come off, the men are pitched in a gladiatorial combat involving a massive stone: One man climbs and pushes, the other tries to avoid getting crushed.

But more than combatants or prisoners, John and Winston are brothers. Their struggle — for survival, for sanity, for keeping their dignity and holding fast to the principles that got them arrested — is compelling in Randle-Bent’s furiously paced production. Key to that struggle: The ancient Greek tragedy “Antigone,” which John and Winston are rehearsing and plan to perform for the other prisoners.

Precisely structured, “The Island” drama plays out in four scenes, each encapsulating a day in the prison, and a scene from “Antigone.”

The prisoners’ choice of a play is apt: In Sophocles’ tragedy, Antigone is sentenced to exile by King Creon for the crime of burying her brother, who challenged Creon’s rule. Antigone knows what she’s risking when she insists on burying Polynices, but can’t deny her own moral compass. When we eventually learn why John and Winston are imprisoned, the parallel between their own acts of civil disobedience and those of Antigone are impossible to miss.

The sibling bond between Antigone and Polynices highlights the brotherhood of John and Winston. The dialogue makes the friendship and iron-clad loyalty between the men readily apparent, but Randle-Bent takes it to another level entirely by giving them a silent, ritualistic handshake that is profoundly moving.

Brotherhood, tyranny, unjust incarceration, revolution — there’s much to unpack thematically in “The Island,” but Randle-Bent propels the dialogue with a clarity that shines like a knife and an urgency that can’t be denied.

“Antigone” is a tragedy and “The Island” never leaves the prison, but there’s an overarching sense of desperate optimism that permeates each play. Creativity, solidarity and honor can endure, even in places designed to crush them.

In Court’s production, that endurance is grounded in the herculean, intensely physical performances by Conner and Ealy. Movement director Jacinda Ratcliffe powers the production with grueling physicality requiring some serious athleticism. Conner and Ealy deliver it with prowess while still being wholly believable as prisoners battered within an inch of their lives.

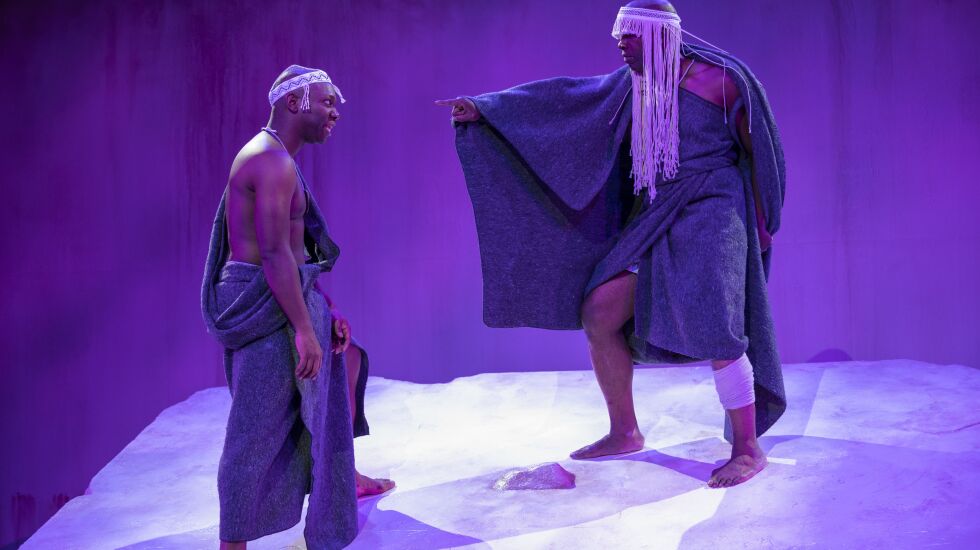

Conner’s Winston has to be sold on playing the titular princess of “Antigone,” his reaction to his costume providing a splash of levity. Ealy’s John is compelling as a passionate, capable thespian who has not been spared many of real life’s brutalities.

Yeaji Kim’s stark set design is dominated by mounds of red sand and a crushing stone slab the men must navigate. Mostly bathed in the harsh, hot colors of fire (impactful lighting design by Jason Lynch) and sun-scoured rock, it’s an effective hellscape. When John and Winston are called to hurl shovelfuls of sand at each other, blinding ropes of red dust swirl across the stage.

In the final moments, we see Winston as Antigone and John as Creon, performing the final scene from Sophocles’ 2,500-year-old play. It’s an acute merger of worlds — the dictums of ancient Greece blending into the punishing world of Robben Island, and today, with eerie impact.