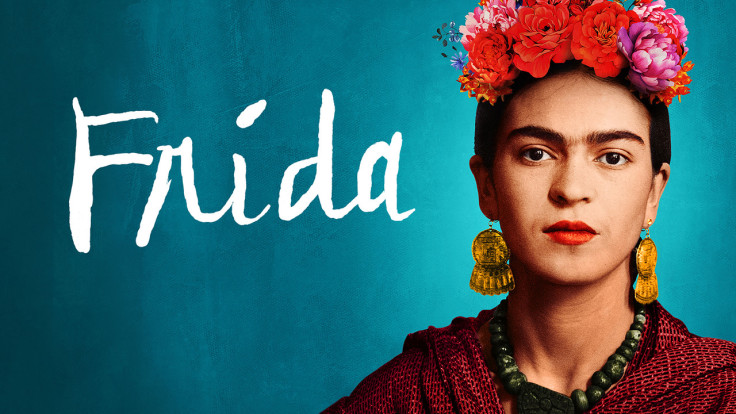

Even if you don't know much about Frida Kahlo, you probably somehow know of Frida Kahlo. Hers is probably one of the most recognizable faces in the world, simultaneously being an icon for the art world, the fashion world, feminism and LGBTQ rights, just to name a few. She got the Hollywood-biopic treatment, she was a character in COCO. Heck, she even became a Barbie doll at one point. So you might be inclined to think that, 70 years after her death, there's little to nothing new to be said about such a popular figure.

But Peruvian filmmaker Carla Gutiérrez wants to prove you wrong.

In her new eponymous documentary, which premiered March 14 on Prime Video, Gutiérrez lets Frida Kahlo tell her story through her own words, drawn from her illustrated diary, letters, essays and print interviews which are recreated thanks to the voice of actress Fernanda Echevarría. All in all, Frida covers more than 40 years of the artist's life thanks to never before seen material that is bound to shine a light on some of the most unheard sides of Kahlo, while honoring her long-lasting influence as a Latino icon and painting a vivid portrait for younger generations.

The Latin Times sat down with Carla Gutiérrez to talk about her approach to the documentary and what she believes is the importance of honoring Latino icons in the most humane way possible.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and translated from Spanish.

What was your relationship with Frida before you started doing this film?

The relationship I had with her was through her paintings, which I discovered when I was a young immigrant in the United States. I was in college and I'd been in the United States for about three years when I first saw a painting of hers where she's standing at the border between the U.S. and Mexico . As a an immigrant, missing my country very much and getting used to this new reality in a country that is sometimes not as warm as you would like, I saw the painting and said "wow, this is my experience, these are my feelings."

Over the years, other paintings accompanied me in different stages. When I went through heartaches, when I felt lonely. When I had children, the painting of her miscarriage was a very significant one at some points of that whole process. So, growing as a woman, my connection with her paintings also grew and I always found refuge in her art.

So how has your relationship to Frida changed after the two-year process of making the documentary?

Well, when we started the movie I really knew all the details of her life. I had read her diary. I'd also read fragments of other letters, of some interviews she did. But gathering all this up and putting it together was very impactful for me, just being able to hear her talk about her emotions, her feelings, about the things she had gone through because of her accident, her miscarriage, the love she had for Diego (Rivera).

We don't know Frida as a fragile person, but she was quite fragile from time to time. And it was also quite beautiful to discover her sense of humor. For me it was very nice to be able to hear her sarcasm, the different ways she could insult people. It was very funny. I just felt that I got to know her deeply. And that was the change for me.

Let's talk about the access you had to Frida's archives and the responsibility you felt in telling her story.

Diego (Rivera) and Frida were both communists and they came from a cultural movement in which they wanted to offer art for everyone. So after Frida's death, Diego granted all of Frida's work to the Mexican people. So the copyright, the permits to use them freely already exists. You have to ask permission from a trust managed by the Bank of Mexico. The thing is that, since she was so prolific, you have to search all the writings yourself because they're not in one place. There are museums in the United States that have many letters. There is a museum in Oaxaca that has letters too. There are also private collections. So that was a big task that my production team did.

I think that in the beginning we did not think that Frida was going to tell so much of the story herself because we did not know that so much of her words actually existed. What we discovered was her spirit, her feelings. She's not narrating details of what happened in her life, she's talking about her reactions to those things. So the responsibility was for us to be able to give her a microphone and let her talk. I think this is different from what has been done before around her figure.

We thought about using other voices more, but Frida took the story and said: "no, , I'm going to say what I want."

What do you think is the importance of stories that speak about Latino icons such as Frida Kahlo? In your movie I feel you're trying to honor this larger than life figure while still offering an intimate look. Do you think that's the way these stories should be told?

Well, speaking specifically about Frida, I did want to present her in an intimate way because she has become such a symbol that it kind of reduces her humanity in a way. With figures like her you no longer see real people, which have complexities and flaws. But the reality is that these were not perfect heroes. So for me the most important thing is to humanize people deeply in all their aspects.

At the same time I feel a responsibility because I'm a Latina filmmaker and I'm really attracted to Latino stories and those are the stories I want to tell. We approached her story with the collective knowledge we have of her culture. Our entire team is Latino, except for a couple of people. It's a bilingual crew, with first and second generation immigrants plus Mexican collaborators which were very important for the whole project to feel authentic. The film is also in Spanish which was essential and we wanted to protect that from the start.

So I feel that there is a double commitment at play: to humanize these Latino icons of ours but to also present them as truly ours.

Why do you think Frida is still such a popular figure to this day? What do you think that says about her legacy?

I believe it is has to do with this need to share our inner worlds. Nowadays we present our image through social media, but we do it with great care. We present our most beautiful sides, the most perfect angles of what we're living and we don't openly talk about the difficult things like traumas or suffering. The sad things, right? Especially for women, I feel there is great pressure to keep that bottled in. So I think that's why decades pass and Frida's art continues to connect with people, because it's so specific and so personal that women and the queer community see themselves in her honesty. There are such relatable, human emotions in her work and in her life.

© 2024 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.