The relationship between France and Germany is often described as the “motor of Europe” but there is one area in which it can be described as dysfunctional: the energy sector.

The situation becomes ever more alarming as each country’s energy strategies grapples with difficulties; this persistent dispute regularly destabilises the entire structure of Fit for 55, the EU’s “climate package”.

How did such patterns arise? An extensive paper published in Confrontations Europe will be our starting point to answer this historical question.

From the 1950s to the coal and petrol crises

In Germany, after the Second World War, the vital resources of coal and lignite played an important role in the country’s reconstruction as nuclear weapons were banned.

The energy sector is at the heart of Germany’s version of corporatism, relying on the role of unions and the Stadtwerke, the regional energy and infrastructure companies. The coal crises of the 1950s and 60s, then the petrol crises in the 1970s, led to more intervention by the federal state with a plan to support the national coal industry and the launch of a nuclear programme.

At the end of the 1970s, coal contributed to 30% of the primary energy supply while nuclear made up 40% of the electricity supply. But these transformations took place in a context of regional geopolitics; in the north-west, regions are historically coal powered and bastions of the SDP (Social-Democrat Party) while in the south-east, conservative provinces dominated by the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) and the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU), support nuclear development on their territory. This split in the public policy community would be leveraged by anti-nuclear campaigners.

Conversely, in France, the defining feature of the energy sector is probably its extreme centralisation, set out in 1946’s Nationalisation Act, that left power to local management and companies only in exceptional circumstances. In this matter, the interests of the EDF and of the state are seen by state technocrats as one.

As was the case in Germany, the petrol crisis of 1973 inspired policies aiming toward energy independence. In practice, the vision of “All electric, all nuclear” would become an ambitious programme, the Messmer Plan, formulated to respond to abundant demand and based on the capacity of the industry to produce a series of nuclear power stations. This was done in service of energy independence and “the greatness of France.”

After the petrol crises and with the climate crisis, two tales of transition

In Germany, the tale of the energy transition, Energiewende, starts in the 1980s, based on the analysis of public intellectuals (Robert Jungk, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker) of the environmental crisis, on anti-nuclear campaigns promoted by the green party Die Grünen, and on the work of energy experts, such as those of the Öko-Institut.

Over time, this critique of the growth model would be replaced by a more consensual vision that promotes the idea of “growth and prosperity without petrol or uranium.” This attitude was slowly taken up by the SPD in the “red-green” alliances at the local level, then at the federal level in the coalitions of 1998 and 2002.

While conservative parties long wavered, the coalition that brought Angela Merkel to power in 2005 argued for the maintenance of nuclear as the “energy of transition”. But the accident at Fukushima rocked public opinion, prompting Germany to abandon nuclear in 2022.

In France, political elites’ support for nuclear remains strong and stable. Neither the Chernobyl catastrophe of 1986, nor the return to power of the “left-wing coalition” has impacted the status quo. On the other hand, after the signing of the Kyoto Agreement in the same year, there was a revival of interest in energy issues: since 2006 the think-tank, the négaWatt association, has regularly called for prudent energy use and a significant role for renewable energy.

After the election of President François Hollande, the national debate in 2013 around the energy transition was an important time for building narratives and helped identify four paths for transition.

The four pathways – ranging from the very cautious with nuclear phaseout to the maintenance of the current model with huge nuclear capacity – is an accurate reflection of current political trends in France.

Since then, as election considerations have halted decision-making, the main documents detailing France’s energy policy (PPE, SNBC) have pushed the issue of nuclear into the long grass.

Or this was the situation when Emmanuel Macron decided to redevelop new reactors just before the presidential elections of 2022.

Fifty years after the first petrol crisis and thirty years after the signing of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, France today has an energy mix twice as decarbonised as Germany’s (52% compared to 26%), even if the proportion that renewable energy makes up is slightly smaller (18% compared to 22%). But the two systems are in crisis.

Today, two models in crisis

In the months following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the French, largely nuclear-based energy system plunged into crisis, with nuclear production falling by 30% compared to the average of the last twenty years.

The sector has responded with a renovation programme for existing nuclear power stations and construction plans of at least six supplementary units. Such initiatives could help atomic power to recover to stable production levels – and yet, this is not a guarantee, particularly in light of France’s increasing use of renewables.

When it comes to Germany, the Energiewende must face up to current new challenges in a dangerous and uncertain context. The original decarbonisation strategy was set out in three stages, consisting of the development of renewals, the stopping of nuclear and then of coal.

One might judge that at the start of the 2020s, the two first phases had been completed. However, in 2022, the country was still heavily reliant on coal, then accounting for 31% of electricity production – up by 11% compared to the previous year.

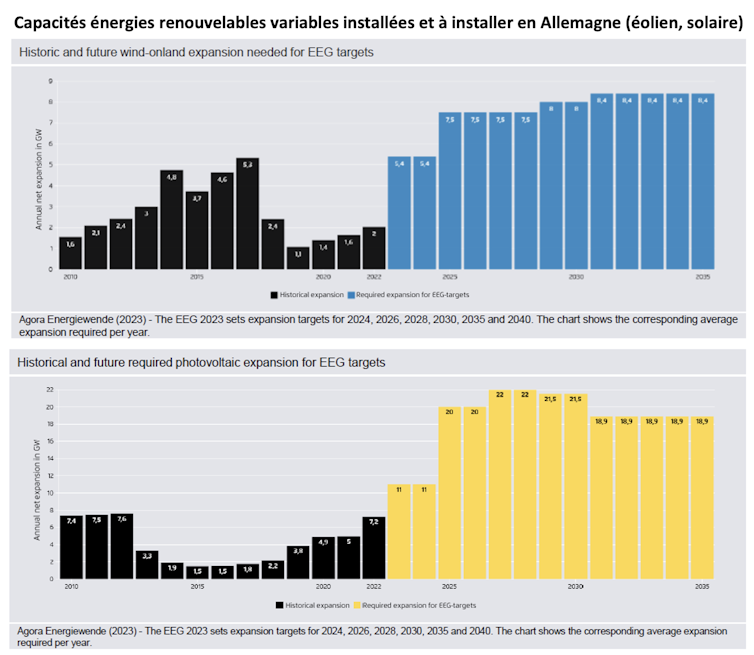

In line with a long political tradition of trade with Russia, the country had set out for Russian gas to act as a bridge fuel from coal to green hydrogen. But the flaws of this strategy were exposed by the invasion of Ukraine. Weaned from Russian fossil fuels, Germany now has to contend with developing renewables at a rate never achieved in the past, while considering intermittency issues.

An imperative for Europe: reconciling energy policy, while respecting national choices

Although countries in the EU are capable of initiating collaborative actions – notable examples being the Green Deal or even the Repower EU plan – a crack is opening up between the nations with very different decarbonisation strategies.

These conflicts broadly pit two blocs against one another: on the one hand, a “nuclear alliance” led by France and followed by the Netherlands, Finland, Poland, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia; and on the other, a group of “friends of renewables” driven by Austria, and backed by Germany, Spain, Denmark, Ireland, Luxembourg, Portugal, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia.

These two coalitions are tearing each other apart over nearly all the big issues in energy transition, including the European taxonomy, the reform of the electricity market and the definition of green hydrogen.

Read more: Nucléaire : retour sur le débat autour de la nouvelle taxonomie européenne

Toward European energy principles

If it is impossible to come up with a one-size-fits-all, “European” model for the low-carbon transition, one can nevertheless try to identify principles which, all while respecting national strategies, would enable Europe to move toward carbon neutrality by 2050 in a coordinated manner.

With this in mind, we believe three principles must hold:

The priority must be placed on the fight against climate change, and thus on the decarbonisation of energy systems.

The range of decarbonisation policies likely to be adopted in Europe must be recognised and accepted.

The actions or the policy of the member states in the elaboration of communal actions must not end up stopping projects by other member states in the trajectory toward decarbonisation.

Priority must be placed on climate, subsidiarity in politics and the principle of “do no harm”. The phrasing at this stage is a little general, but one can hope that an effort will be made for both for mutual understanding between the representatives of member states and for a legal-administrative definition at the level of the Commission. This could allow for rapid progress toward a coherent European policy for the energy transition.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.