The last time Jeff Fort was seen outside prison walls during the late 1980s, he was the defiant leader of one of Chicago’s most violent street gangs who once offered to commit terrorist attacks for a Libyan dictator.

After nearly 40 years in virtual solitary confinement in a federal supermax prison, the 76-year-old Fort has appealed for leniency, saying he’s an ailing grandfather who wants to be with his family.

Earlier this year, he sent a handwritten plea to a federal judge in Chicago under the First Step Act, which allows sentences to be reduced for elderly or ill prisoners.

“Given the length of time that defendant has been in custody, much of his immediate family is decease (sic),” Fort wrote in blocky handwriting. “Defendant wishes to take the time to rekindle his personal relationship with his children and forge a new relationship with his grandchildren who were born after his incarceration.”

But U.S. District Judge John Tharp tossed Fort’s request, ruling that Fort deserved the 80-year sentence handed down in 1986 after his conviction for offering to bomb buildings in the United States in exchange for $2 million from Libyan strongman Moammar Gaddafi.

As the judge noted, Fort had coordinated the Libya plot from inside a Texas federal prison while serving time for drug trafficking, directing gang lieutenants during near-daily collect calls to the Chicago headquarters of his El Rukn gang.

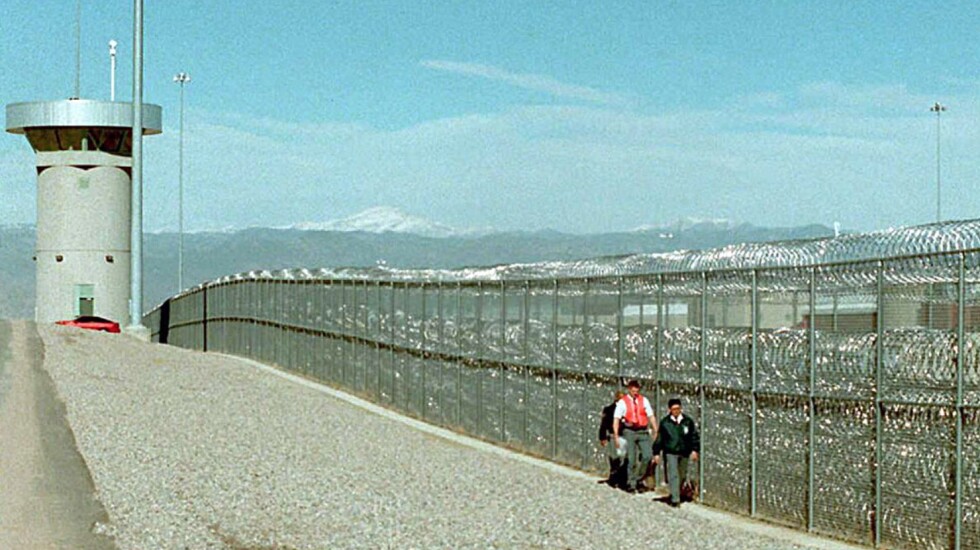

Fort has spent most of that sentence in a maximum security prison in Florence, Colorado, and has almost no contact with other inmates or the outside world. At the request of prosecutors, he has been allowed access only to a phone to talk with his lawyers or immediate family.

Tharp said he saw no reason to change things.

“Fort’s willingness to kill indiscriminately and for profit mark him among the most dangerous of criminals — and as one for whom a sentence reduction is entirely inappropriate,” Tharp wrote.

“That Fort has not been a disciplinary problem ... and has completed many classes offered to prisoners are positive developments, to be sure, but they fall well short of assuring that the ruthless El Rukn ‘Imam’ has morphed into a gentle grandpa who wants nothing more than to spend his remaining years with his grandchildren.”

Tharp called Fort’s bid for freedom “quixotic.” To actually go free, Fort would also have to reduce a 75-year sentence handed down by a state judge for ordering the 1981 murder of a rival drug dealer.

The judge’s ruling saddened but did not surprise Fort’s daughter, activist Ameena Matthews, who has vowed to continue her father’s fight for an early release from prison.

“My first priority is to reestablish communication with my father, to make sure that he is OK,” Matthews told the Sun-Times.

COVID-19 restrictions, on top of already strict supermax security, have kept her from talking to her father since before the pandemic. “In his [latest] conversation with us,” she said. “It was clear, he’s in his right mind, and he’s strong, and he’s going to fight until the end to make sure that justice is on his side.”

‘He is an educator’

Matthews said her father is a charismatic community leader who could bring peace to the neighborhoods he once ruled, a belief she says is shared by residents of South and West side neighborhoods plagued by gang violence.

“If he was out, I believe the violence between African American communities and gunfire would be lessened,” Matthews said. “He was an educator. He is an educator. He is still alive.”

Fort’s infamy once rivaled that of his gangland contemporary, Gangster Disciples founder Larry Hoover.

Today, Hoover and Fort are locked up in the same federal prison. But even in virtual isolation in prison, Hoover remains something of a public figure. Fort has largely faded from view.

Like Hoover, Fort styled the Black P. Stone Nation as a community organization, providing programs that attracted support from some of the leading philanthropic organizations in the country.

But the city’s record murder totals in the 1980s and 1990s coincided with the peak of gang figures like Fort and Hoover.

Both Fort and Hoover are seeking sentence reductions under the federal First Step Act, a 2018 legislative package that allowed judges to consider “compassionate release” for aging, ill inmates serving long sentences.

Hoover’s request got a boost from Chicago native Ye, and his then-wife Kim Kardashian in 2021 carried a plea for a pardon to President Donald Trump. Ye also hosted a sold-out benefit concert at the Los Angeles Coliseum co-headlined by rap star Drake.

Members of Hoover’s legal team included Jennifer Bonjean, an attorney whose client list has included Bill Cosby and R. Kelly. His plea for leniency was denied in 2021, but he has asked the judge to reconsider — though, like Fort, he also has a state prison term to complete even if released from federal prison.

Meanwhile, Fort has struggled for decades to find attorneys willing to work on his case, according to his daughter. Fort drafted his own petition for compassionate release in February, as well as a separate petition asking the judge to allow a fellow supermax inmate, serving a 40-year sentence for sexually assaulting prisoners in a federal lockup in Alaska, to assist with future filings.

“They have him under the mountain,” Matthews said in a recent interview, referring to the federal prison in Colorado. Other inmates there include Oklahoma City bomber Terry Nichols, mob boss James Marcello and 9/11 plotter Zacarias Moussaoui.

Only an attorney or his immediate family can visit Fort, and no one has been able to make the trip since before COVID-19 precautions locked down the prison, his daughter said.

Prison officials agreed that Fort met some of the criteria for compassionate release, but they denied his petition based on the nature of his charges and his leadership role in El Rukn. They did allow him more freedom of movement inside the prison and have given him more access to make phone calls, Matthews said.

“When he was able to move around a little was when he was able to get someone to help him,” she said.

A ‘pretty unbelievable’ plan

Hoover was brought down by an investigation that initially targeted his gang activities related to running a drug-trafficking operation, fairly run-of-the-mill stuff for the FBI agents and cops on the case.

What federal agents heard when they tapped the phones at “The Fort,” the former South Side theater the El Rukn had turned into a fortified headquarters, shocked them. Fort, who was serving a drug-trafficking sentence at a federal prison in Texas, was making daily collect phone calls to Chicago.

He was coordinating not only the vice and violence on El Rukn turf on the South Side but also plotting an elaborate plan for the El Rukns to commit acts of domestic terror in exchange for a $2.5 million payout from Gaddafi.

At the time, Gaddafi’s government was providing clandestine support to groups in Palestine and even Northern Ireland. Fort’s 1986 indictment was handed up just weeks after President Ronald Regan had ordered U.S. airstrikes inside Libya because of Gadhafi’s purported support for the perpetrators of a bomb attack at a Berlin nightclub.

While Fort had converted to Islam and added elements of the Muslim faith to the gang’s message of empowerment, police believed the tilt toward religion was intended to make it harder for law enforcement to get search warrants and wiretaps approved, according to Patrick Deady, a former federal prosecutor who helped build the case against the El Rukn leaders.

Deady was skeptical that a shared ideology or religion drove the El Rukns’ desire to collaborate with Gaddafi. Fort was reportedly envious of $5 million the Libyans had paid to fellow Chicagoan Louis Farrakhan and his Nation of Islam, and so he sent his emissaries globetrotting for meetings — in Libya and in a Libyan embassy in Panama — to negotiate the $2.5 million payout.

Deady admits he doesn’t know if Fort intended to carry out acts of terror or just pocket the Libyan’s money, but the gang seemed serious. In a sting operation, El Rukn members bought what they thought was a working anti-tank rocket from an undercover FBI agent.

The charges against Fort and his top lieutenants marked the first time American citizens were charged with plotting acts of terrorism inside the United States, Deady said.

“It was pretty unbelievable,” said Deady, now a private attorney. “This was all pre-9/11, and here we had concrete evidence of someone planning acts of terror, blowing up buildings, inside the United States. Don’t think [the El Rukns] were political. I think they were mercenaries. I think they would have done it for money.”

One reason Fort may never walk free is that his case is not a particularly good one for those who support sentencing reform.

The federal First Step Act provisions largely target reducing prison time for nonviolent drug offenders who received stiff sentences during the 1980s and ’90s furor over crack cocaine.

While the national mood about crack has become less panicked over the decades, public sentiment about terrorism has gotten only darker since the 9/11 attacks, said Richard Kling, an IIT-Kent Law School professor who has represented lower-level El Rukns.

“I don’t think that (the public perception of terror bombings) is going to change any time soon,” said Kling. “Some people they will never let out because of who they are and what they did.

“Jeff Fort may be one of those people.”