Romila Thapar is one of the best known critics of Hindutva politics. Often criticised by the right wing for her independent views, Thapar still raises her voice for a pluralist India. Her new book, The Future in the Past, is a collection of essays on issues and ideas that have preoccupied her as a historian. In a conversation, Thapar explains how Hindutva politics seeks legitimacy from a supposedly Hindu past to the exclusion of others. Excerpts:

How do you look at the Hindutva approach to history?

An approach to history usually involves a theory of explanation. This means gathering reliable evidence on the subject to be researched, which is then analysed, and a logical explanation sought for past events. None of this is required for the Hindutva approach to history which is largely the description of a past so constructed that it provides legitimacy for an ideology of present times. There is no check on whether the evidence is reliable and the explanation based on well-reasoned arguments. Professional historians therefore do not take it seriously.

The purpose of Hindutva history is to maintain that the proposed Hindu Rashtra is the predictable outcome of the past of India. The focus is on the history of Hindus thought to be the most relevant compared to others. Recent deletions in the history textbooks such as Mughal history are a case in point. Contributions to the past came from varying sources, but for Hindutva only the past of Hindu communities is of any real consequence. For Hindutva, current politics should be conducive to bring about a Hindu Rashtra.

Modern scientific achievements are said to have been known millennia ago to learned Hindus — an idea that gives rise inevitably to incredible claims, such as the antiquity of flying machines, plastic surgery being used literally to create the deity Ganesh, or stem-cell research in the birth of the Kauravas. None of these claims is based on proven evidence. It underlines the difference between trained historians and those claiming to be writing history.

Why does a section of academia and a significant section of politicians have this urge to own the Aryans and emphasise their alleged indigenous origin?

In pre-colonial times the term arya was applied to those whose language evolved from the Aryan language and who were socially worthy of respect. The king is sometimes called arya-putra. In the culture of the Iranian Aryans in ancient Iran, the Achaemenid rulers took pride in identifying themselves as Aryas and as Aryan speakers. Culturally, the Iranian Avesta shows some curious links with the Rigveda.

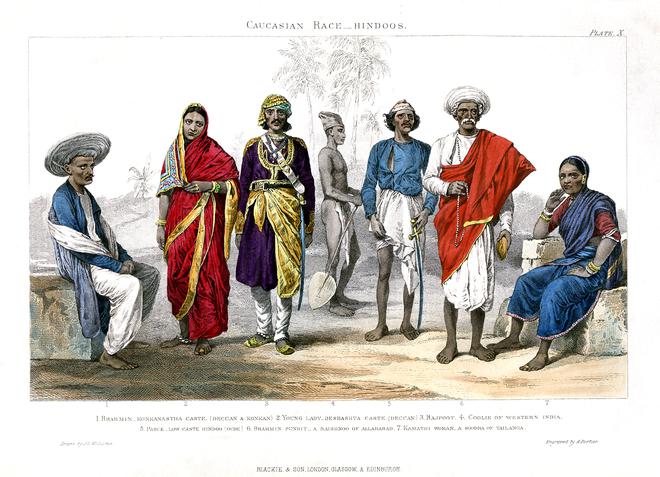

In the 19th century the term ‘race’ came into prominence and the study of peoples around the world was labelled ‘race-science’. Dividing people into races introduced a hierarchy, and in this the Aryans were placed high. It was taken to a horrific extreme by Hitler and the Nazis supported by Mussolini and the Italian fascists. Indians linked to Hindutva such as B.S. Moonje, were deeply impressed and aimed to model their own organisations on these lines. Added to this was colonial scholarship that regarded the Aryans as superior.

In the Indian context, the Celtic culture of the British Isles was thought to have some similarities with Indo-Aryan cultures. The speakers of the Indo-Aryan language, Sanskrit, were projected as the original Hindus and their religion, Vedic Brahmanism, was foundational to Hinduism.

Savarkar defined the Hindu as the one who could claim that India was the land of his ancestors, pitribhumi, and was also where his religion originated, punyabhumi. The Aryans therefore have to have originated within India. Hence the desperate search for an Indian homeland of the Aryans, and the Hindutva denial of migrations into India from Central Asia by Aryan-speaking peoples.

The creation of a national culture was anti-colonial in nature. How has it devolved into the concept of Hindu Rashtra today?

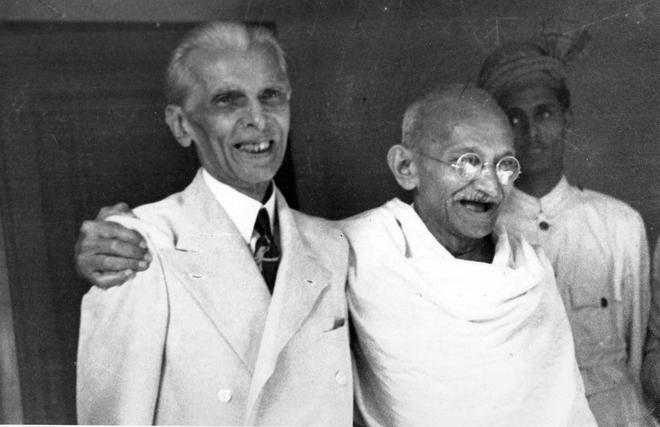

Historically there have been two categories of nationalism in India. The earlier one which was much bigger, more inclusive, and that had the support of the majority of Indians, across all communities, was what has been called — and rightly — the nationalism of the Indian National Movement, seeded in the late 19th century. As a movement it was inclusive and drew in every Indian, irrespective of other identities such as religion, language, class or caste. It had one main purpose which was to end colonial rule and convert India into a free, independent nation-state. I would call this as inclusive, integrated nationalism. A nation-state was achieved in 1947. The essential characteristics of this nationalism were democracy and secularism that would help to ensure the equality of all citizens.

Alongside this integrated nationalism was another movement that has been called religious nationalism. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, two movements began to take shape. They called themselves nationalisms but were based on limited majorities and qualified by a single religious identity. The Hindu identity was the religious majority of the population, and the Muslim identity was in religious terms, the largest minority in India. Neither of these two was centrally concerned about organising against colonial power. Each of the two planned to establish two successor states after the departure of the coloniser. One was Pakistan which would cater to the Muslim majority among the minority communities, and the other was the Hindu Rashtra that would cater to the Hindu majority in the population.

How did this come about?

Their genesis lay in the colonial reading of the Indian past. Colonial scholars argued that pre-modern Indians lacked a sense of history as there were no histories of India dating to pre-British times. So they set about investigating India and came up with the theory that there had been two religious ‘nations’ — the Hindu and the Muslim — that had dominated history, and had been deeply hostile to each other. The manifestation of this theory took shape in the various parties supporting the two nationalisms qualified by religion — such as the Muslim League supporting Muslim nationalism, and the Hindu Mahasabha, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh etc. supporting Hindu nationalism. The chickens of colonialism came home to roost in these religious nationalisms.

In contrast to inclusive, integrated nationalism, religious nationalism is defined by its being exclusive and segregating, concerning itself with the well-being of largely only those who identify with its religious identity, or for that matter any other single identity of either language or caste.

Religious nationalism is a party of co-religionists. Because it is exclusive it segregates itself from other nationalisms, and to that extent can be appropriately called segregated nationalism. Its central purpose is to establish a nation-state for the well-being of those belonging to a single signified religion, generally the religion of the demographic majority, as in the case of Hindu nationalism. This severely contradicts two essential characteristics of the nation-state — that it must be democratic and secular in its functioning. In the absence of this functioning, the mutation of such states into political authoritarianism is always feared.

Is the modern concept of nationalism a ruse for politics of exclusion?

It depends on which kind of nationalism one is speaking of. It is important to make a distinction between integrated nationalism and segregated nationalism. As long as integrated nationalism prevails there is unity of purpose, as there was in India initially after 1947. We were then concerned with building a society ensuring the welfare of all and took at least a few steps to do so. It wasn’t just a matter of making speeches for electoral support and leaving it at that. After all, we do have a Constitution to guide us in what we might be doing or planning. Integrated nationalism does not make a distinction between ‘we’ and ‘they’ since every citizen is included. But segregated nationalism does make a distinction, giving priority and privileges to the ‘we’ and subordinating the ‘they’. Sometimes it is even a violent subordination to press home the difference between the dominant majority and the lesser others. This does not happen in integrated nationalism because the majority in this form has people of mixed qualifications. In this the composition of the majority is not permanent and based on a single identity as it can change when the subject of discussion changes.

The Future in the Past: Essays & Reflections; Romila Thapar, Aleph, ₹999.

ziya.salam@thehindu.co.in