Last year, more than 1,200 people died in road crashes across Australia. But not all Australians face the same level of risk on our roads.

Government data across five states and territories show significant inequity in road safety.

Data from New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory show First Nations people are about 2.8 times more likely to die on the road than non-First Nations Australians.

One thing we can do to reduce this transport inequity is make it easier for First Nations people to get their driver’s licence. This will not only improve road safety. This will bring individuals and communities many other benefits.

There’s a huge difference

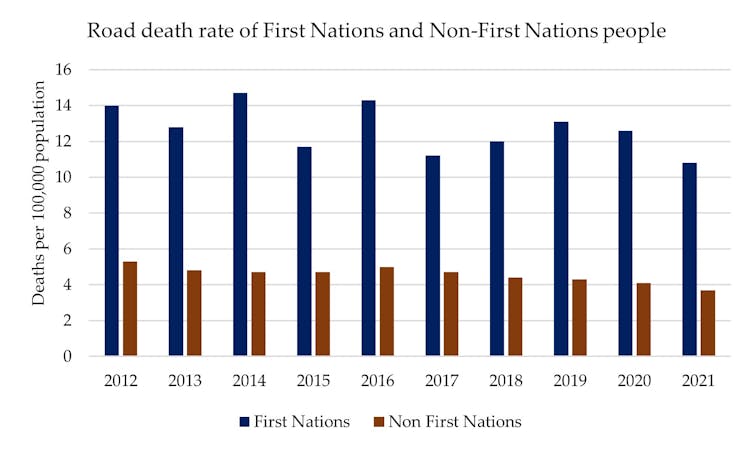

Between 2012 and 2021, 791 First Nations people died in road crashes. This is 12.7 out of every 100,000 First Nations people.

In comparison, the rate for non-First Nations people was 4.6 people per 100,000 population.

Among First Nations people, those aged 26-39 face the highest risk of a road death, with a rate of 20.9 per 100,000 population. While the risk for those aged 40 and older has steadily declined since 2016, the risk has risen for the 26-39 age group in recent years.

Fatal road crashes involving First Nations people mainly occur in inner and outer regional areas, and remote and very remote areas of Australia. For instance, of the 76 road deaths of First Nations people in 2021, only 13% took place in major cities.

There is also a notable gender difference in the circumstances of road deaths involving First Nations people. More than 40% of female road deaths occur as car passengers and 23% as pedestrians. But males are more often drivers, motorcyclists or cyclists.

Driver’s licences are a real issue

Unlicensed drivers are at greater risk of dying on the road or being involved in serious crashes. And one crucial factor contributing to the higher road fatality rates in First Nations people is the significant barriers faced in obtaining a driver’s licence.

Licensing rates among First Nations people are lower compared to the general population. For example, only 51-77% of First Nations people surveyed across various sites in NSW and SA held a driver’s licence, compared to 83% in the general population.

This disparity is deeply intertwined with the impact of colonisation and the way laws around driver licensing are imposed and implemented.

My research (Masterton) in rural Australia demonstrates what this means in practice.

What if you can’t afford a car or lessons?

In research yet to be published, I am exploring transport challenges First Nations women face in rural Queensland. Through yarning, interviews and brief surveys, several common barriers are evident.

Some women have a licence or learner permit. Others have expired licences and are struggling to renew them. Most, however, have no licence. A significant number (licensed or unlicensed) have no access to a roadworthy vehicle or cannot afford one.

Many women without a licence still drive out of necessity: to take their children to school, go to work or care for family. Most, however, rely on walking or getting rides to manage their daily lives. Only a small fraction of the women, who had both a valid licence and a car, expressed feelings of freedom, independence and higher self-confidence.

During visits to remote communities, it became clear First Nations people who took part in my research are not resistant to getting their licence.

Research also shows First Nations people do not have poorer attitudes to road safety than non-First Nations people. However, the licensing process needs to be culturally appropriate and accessible to encourage participation.

Obstacles such as literacy barriers, the complexity of navigating a system designed for native English speakers, mistrust of authorities and the high costs associated with getting a licence, all contribute to the low rates of licensing.

There are challenges related to providing adequate identification documents (such as birth certificates), and finding driving instructors who can effectively work with First Nations people.

The high cost of driving lessons, difficulty in accessing a licensed driver to supervise practice hours, and the financial burden of unpaid fines for driving unlicensed further complicate the path to getting a licence.

Addressing these issues could make a significant difference in improving transport equity and road safety for First Nations communities.

It’s not just about transport

For many First Nations people, particularly those in remote areas, the ability to travel safely and legally is crucial for accessing health care, fulfilling cultural responsibilities and participating in the workforce.

So the issue of reduced driver licensing in First Nations communities is also a profound social justice issue that impacts the broader health, wellbeing and autonomy of these communities.

This means the barriers to getting a licence – whether financial, logistical, or bureaucratic – exacerbate existing inequalities. It creates a ripple effect, limiting mobility and reinforcing social and economic disadvantage.

How do we address this?

Addressing the licensing gap requires coordinated efforts across multiple sectors, including health, education, transport and justice.

Community-driven programs, financial support and policy changes can all make licensing more accessible.

There have been community-based pilot programs aimed at supporting First Nations people getting their licence in NSW and the NT.

The programs provide culturally tailored, community-based licensing support through intensive case management, mentoring, and addressing specific barriers to access and navigate the licensing system, and to obtain and reinstate licences. These pilot programs have shown great promise and effectiveness, indicating that they should be scaled up and rolled out more widely, with community support.

Licensing is also a justice issue. Some one in 20 Aboriginal people in jail is serving a sentence for unlicensed driving and other driver’s licence offences.

So First Nations sentencing courts and other programs designed to divert people from jail could also help First Nations individuals get their licence and limit further contact with the justice system.

In this article we use the term First Nations people, which we adopt from the Uluru Statement of the Heart.

Milad Haghani receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Teresa Senserrick currently receives funding from the Western Australian Road Safety Commission and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and previously from the Australian Research Council.

Gina Masterton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.