If you want a little insight into just how much the sporting world has changed in the last 72 hours, take the story of one prime footballer who previously didn’t even consider an offer from the Saudi Pro League. The numbers and headlines being shared suddenly made the unnamed player do an about-turn and contact his agent to ask whether a deal was still on the table. His mind has been changed.

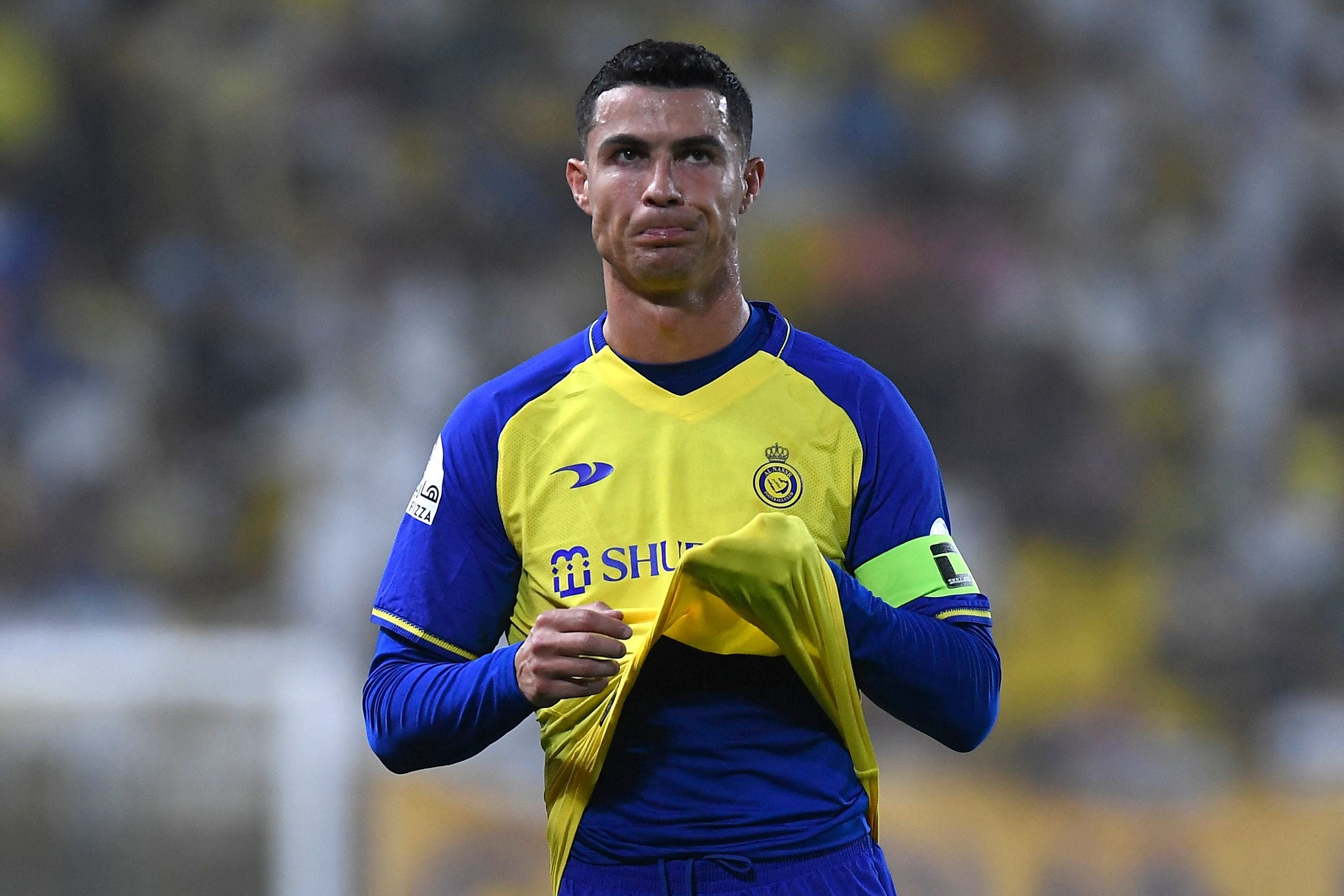

That player is not Neymar, although he is the next big target after Lionel Messi, and a huge offer has been put forward to the Brazilian. They are the tier of top stars, along with Cristiano Ronaldo, who connected sources insist are the only ones getting more than £50m a year. Those are game-changing sums, since they are substantially more than the pay of the entire Luton Town squad just promoted to the Premier League.

This is a game-changing moment. It was Ronaldo’s initial move that sparked it. It is the LIV Golf story that has, well, brought it to the fore. However, it is only with the one true global game – football – that we can see how much sport has really transformed in the last 72 hours.

What Saudi Arabia is attempting is a takeover of the planet’s primary cultural pursuit. Some of that does stem from genuine social programmes within the state, particularly to tackle obesity. Most of it comes from the kingdom's “sportswashing” aims, as it attempts to preserve a power structure as oil revenues diminish. All of it, ultimately, comes from crown prince Mohammed bin Salman’s marriage of brutal suppression with what human rights activist Iyad el-Baghdadi describes as a “desire to be loved”.

That contrast in approach almost perfectly applies to what has happened with golf. The sport was split apart so one side could be co-opted, with Saudi Arabia now a part of its infrastructure. A fist and then an open hand.

While football awaits similar, it should reflect on the fact that this exact move has already been tried twice.

The game had anticipated a first split with Gianni Infantino’s initial plan for an expanded Club World Cup in 2020, and a number of sources state that Saudi money underpinned the SoftBank fund for that. That break was put off by new agreements made for the Covid pandemic, only for the ensuing financial crisis to push stricken clubs into rushing the European Super League. Again, the same sources state that Saudi money underpinned the JP Morgan loan for that.

Unlike golf, however, the sport’s unique supporter culture kept the game together. It did not break.

Saudi Arabia is now trying another approach. Or, rather, every other approach.

The playbook set by their Gulf neighbours in Abu Dhabi and Qatar has been followed and significantly updated, as the world now moves onto the next stage.

Saudi Arabia first went down the simple sponsorship route, as was most visible in so many deals with Manchester United. They then sought to fund the plans of others, as with Fifa’s Club World Cup, while staging events such as the Italian and Spanish Super Cups. They then bought a club in the most prominent league in the world, with Newcastle United. They are now seeking to revamp their domestic league, all to build up to the most traditional form of sportswashing of all, which is the staging of the World Cup itself.

That is the great ambition for 2030, which is of course the year marked for the culmination of Bin Salman’s grand economic plan.

It was as part of the announcement of the latest plans for ‘Vision 2030’ that a new era for the Saudi Pro League was launched.

One irony is that the overhaul of the domestic league could otherwise be seen as a legitimate development. Saudi Arabia has a vibrant young population that is obsessed with the sport, and a very strong and long-standing football culture. It has produced a series of fine teams at Asian club level as well as two highly respectable World Cup performances, and the quality is generally described as good. There’s even an argument that a vibrant league has just been waiting to be developed there.

It’s just that it’s impossible to isolate from Bin Salman’s wider political aims, with human rights campaigners FairSquare describing it as “central to Saudi Arabia’s soft power strategy”. There is similarly a belief within football that the unusual nature of the overhaul could represent a model that soon spreads and upends the wider game.

It, admittedly, isn’t expected to be as bombastic as the Chinese Super League, which briefly sent waves through the sport through huge fees and wages back in 2016-17. The Saudi Pro League is nevertheless seen as more of a disruptor because it is more sustainable.

As part of the plan, the state’s Public Investment Fund has taken over four of Saudi Arabia’s top football clubs – Al Ahli; Al Hilal; Al Nassr, who have Ronaldo, and Al Ittihad, who will have Karim Benzema. Those with direct knowledge of the preparations say the rationale is from research that the most vibrant leagues need a “top four”, in order to create a sense of competition and drive broadcasting markets. ‘‘You’ve got to have a top four,’’ in the simple words of one source. This has already led to some internal friction, as Riyadh’s third biggest club – Al-Shabab – have now missed out.

They are instead one of 12 clubs who will likely get one top foreign player each, but the new big four will get three. The aim is then for this to raise the level of Saudi football as a whole, alongside the value of the league. It is hoped to make it worth £400m a season by that landmark year of 2030.

The initial idea is that it becomes the natural home for stars in their mid-thirties looking for a last payday, since there is an obvious space there. The Chinese Super League is now gone as a force and the USA’s Major League Soccer is too constrained by regulation. The Saudi Pro League also has the attraction of huge crowds, unlike Abu Dhabi or Qatar. From there, the age of foreign stars would gradually be brought down, as the quality of homegrown players goes up.

A number of big football industry figures have been invited over for consultations over the last few months and they have been struck by the substance of the idea. There is a belief that, while the competition can’t ever get to Premier League levels, the money involved can eventually bring it to a point where there are more high-profile prime stars than either Ligue 1 or Serie A.

“It’s not going to be a significant league in the true sense,” one prominent source argued, “but it could be an interesting league.”

To do that, though, the competition is going to need proper structure and regulation and that is where some of those consulted have been struck by the “eruption” of the last few days. It is like it all suddenly got super-charged. The Saudi state announcement ensured offers for players have been flying around, some of them greatly increased after the initial refusal, some of them clearly from actors looking to exploit the situation. Players have been getting contacted by six different intermediaries, all insisting they represent the same client or club.

One source tells the story of a player called by an agent who claimed to be sitting right beside a “prominent member of the royal family, who loves you”. Another call minutes later revealed that to be bogus.

“It’s creating chaos,” the source says.

Others with knowledge of the Saudi plans do insist some of the numbers going around are also bogus. While there is an admittance that Ronaldo, Neymar and Messi would be on the highest figures, they are adamant those for Benzema and N’Golo Kante do not go beyond £50m and £30m a year, respectively.

After that, it is a sliding scale, if still an attractive one. Maybe not attractive enough for Messi, though.

As of Wednesday afternoon, and despite extensive negotiations with his father Jorge, the Argentine had agreed a deal in principle with MLS franchise Inter Miami. The Messis have kept the door open, though. The Saudi Pro League will meanwhile just move onto the next major target, which is Neymar.

Messi’s decision nevertheless points to a potential “new world” in football, that has inevitably risen with the sport’s recent explosion in global popularity, and potentially has opposite poles represented by the hosts of the next two World Cups.

While the USA already has 2026 along with Canada and Mexico, Saudi Arabia is currently the favourite for 2030. That’s what much of this is building up to.

There will be conflicting powerful emotional pulls on the process since that year represents the centenary of the first ever World Cup in Montevideo, as marked by a joint bid from Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay. Another bid from Spain, Portugal and Ukraine will be similarly alluring.

It is maybe the strongest ever field of bids, but Saudi Arabia has a strong claim of its own, namely in money. Despite the fact that any such bid would face an avalanche of criticism over human rights, Qatar is already seen as crossing a threshold there, and the Kingdom has been canny in who it has corralled into its bid. The inclusion of Greece will split European votes. The inclusion of Egypt will split North African votes.

There is even a theory now openly being stated that a deal will eventually be done with South America to bring Uruguay in. Montevideo would then be able to host the opening game, with Saudi Arabia underwriting the costs.

This is the power of that kind of money, that football is proving as unresistant to as golf. It is why the reshaping of the Saudi Pro League is being viewed as the most interesting move – and, in many quarters, the most ominous move – of all. Many in football believe it represents a template for autocratic states eventually buying stakes in leagues.

Private equity groups like CVC have already attempted similar with a number of sporting competitions, including La Liga. It would make sense, at least in sport’s perpetually greedy world, for states to be the next step.

For many, up against the unparalleled power of the Premier League, it could even prove obvious. If it is a struggle for anyone else to match the Premier League’s power, then just do a deal with an autocratic state to lift the competition as a whole.

The Premier League itself may not even be off-limits.

“Anything is possible,” one prominent football executive says. The Premier League would just need to issue new shares and require a change of articles with a 75 percent vote, along with Football Association approval. Or, a new league could just be set up inviting clubs to join.

“And you can be sure the football authorities aren’t even thinking about such challenges,” the same source argues.

A mistaken recent belief in football has long been that any regulation can only ever be reactionary. It has left the sport unable to resist the influence of private equity and autocratic states. By the time those in power realise there are problems with that, it is all too integrated; the imperfect marriage of short-term greed from within and long-term political aims from outside. That has already happened in the sport, as an Abu Dhabi project at Manchester City aims for a treble.

Nick McGeehan, of human rights group FairSquare, sums it up.

"The LIV merger with the PGA is further evidence of how central sport has become to Saudi Arabia's soft power strategy, and the proposed revamp of its domestic football league, in tandem with a World Cup in 2030 and the ownership of Newcastle United will also be key elements," says McGeehan.

"Whereas golf brings respectability, football brings mass appeal and popularity, and Saudi Arabia needs both of those things to deliver on its ambitious domestic plans at a time when Mohamed bin Salman's goons still have their boots very much on the throat of civil society."

The entire era may now be moving onto its next stage, centred in Saudi Arabia.