After a decade of falling interest rates and central bank largesse, global financial markets are facing a reckoning.

Soaring inflation is being met by rising interest rates, the slowing of central bank asset purchases and fiscal shocks, all of which are sucking liquidity, the ability to transact without dramatically moving prices, out of markets.

Violent, sudden price moves in one market can provoke a vicious loop of margin calls and forced sales of other assets, with unpredictable results.

“The market is so illiquid and so erratic and so volatile,” Elaine Stokes, a portfolio manager at Loomis Sayles, said. “It’s trading on every impulse and we can’t keep doing that.”

Policymakers are paying close attention to market plumbing and financial stability risks, with the vice-chair of the Federal Reserve last month warning a “shock could lead to the amplification of vulnerabilities”.

Disparate shocks — like the closure of the nickel market in London, structured product blow-ups, the bailout of European energy providers or the rapid pensions crisis in the UK sparked by turmoil in the country’s government debt prices — are being scrutinised as oracles of wider dislocations to come.

With risks rising, investors are watching some bits of the market more closely than others. Eric Platt

European repo markets

A rapid shift to higher interest rates is fuelling dysfunction in Europe’s money markets, threatening to undermine efforts to tighten monetary policy.

The legacy of large-scale asset purchases, known as quantitative easing, in the eurozone and the UK is a flood of liquidity in the form of central bank reserves that were created to buy government bonds. Those bonds were hoovered up by the European Central Bank and Bank of England, leaving relatively few available to investors.

That scarcity of safe short-term debt may be hurting the euro area’s €10tn repo market, the International Capital Market Association, which represents the biggest players in global bond markets, warned earlier this year.

The little-followed repo market serves as a vital lubricant in daily trading, as it allows investors to take out a short-term cash loan against the assets they hold.

ICMA argued the shortage was distorting interest rates for prized collateral like short-term government debt, and pushing it well below the ECB’s deposit rate, which rose to 1.5 per cent last month having risen above zero in September for the first time in more than a decade.

A similar dynamic has gripped UK markets, where, at the start of November, an index of overnight repo markets fell below the Bank of England’s policy rate by a record amount, according to analysts at ING. These distortions typically worsen at quarter and year-end.

ICMA urged the European Central Bank to set up a reverse repo facility similar to the one introduced by the US Federal Reserve in 2013. That would allow the central bank to ease the collateral squeeze by loaning out some of the bonds it holds from its extensive asset purchasing programmes.

“Central banks are effectively conducting a bit of an unprecedented experiment by hiking rates when liquidity in the system is at such high levels,” said Antoine Bouvet, an interest rates strategist at ING. Tommy Stubbington

US Treasury market illiquidity

Liquidity has long been the hallmark of the US Treasury market. But it has dried up as the Federal Reserve has ratcheted interest rates higher, and as major holders of Treasury debt such as the Fed and the Bank of Japan have stepped back.

The disruption in liquidity has led some investors to question the overall health of the market. Any crisis in the Treasury market would have far-reaching consequences, because Treasury yields determine everything from mortgage rates to the cost for the US government to borrow. It is the backbone of the global financial system and the benchmark for all other US assets, so large swings in price would ricochet across markets.

On top of the uncertainty and volatility in the market this year that has made Treasuries harder to trade, wary investors also argue that the liquidity issues are the result of longstanding structural problems. Some have always existed, but have been accentuated as the Treasury market has grown in size. And some have emerged as regulations following the 2007-09 financial crisis — which forced banks to have larger capital cushions — have made it more expensive for them to hold Treasury debt. Since then, those banks, traditional providers of liquidity, have retreated from the market.

This means that in the event of a crisis, structural problems may exacerbate any sell-off, as was seen in March 2020. But the current liquidity issues in the Treasury market also mean it may not take an event as disruptive as the onset of a global pandemic to spark a big sell-off. If some mis-step prompted a dash for cash, investors could have trouble selling Treasuries, leading to huge swings in prices, producing big enough gaps in prices to lead to forced selling. Kate Duguid

Dysfunction in Japanese government debt

For several months now, as the Bank of Japan has been forced to work ever harder to hold interest rates on the benchmark 10-year bond close to zero under its “yield curve control” policy, speculation has mounted on whether markets would ultimately force the central bank’s governor, Haruhiko Kuroda, to back down and loosen the policy.

Japanese rates analysts and BoJ watchers tend to think he will not; foreign funds and traders believe that he might.

Logically, say analysts, the BoJ will be exceptionally cautious about an exit from yield curve control, because of the potential for a disorderly exit to send shockwaves around the world.

High in the memory of Japanese central bankers is the 2015 experience of the Swiss National Bank, which suddenly lifted its ceiling on the franc, resulting in a huge effect on global markets.

Switzerland, compared to Japan, is small and the disruption that would be caused by a similar capitulation would be massive. Domestic stocks would plunge, with the ripple effect from a Japanese equity crash turning global funds into forced sellers.

Deutsche Bank economist Kentaro Koyama noted that in the minutes of the BoJ’s September monetary policy meeting, one board member had spoken up about the increasing dysfunction of the bond markets.

“We consider it an important step towards a recognition among board members of the flailing functionality of the markets,” said Koyama. Leo Lewis

Stuck in credit

For years, corporate bond and loan investors warned about the dangers of exchange traded funds in a crisis, raising concerns over how the popular vehicles would cope with large redemptions in a sell-off.

But now, as the size of both the private credit and leveraged loan markets have exploded over the past few years, ETFs are seen a less of a menace. Instead, focus has shifted to mutual funds and other vehicles that have been hoovering up the recent surge of risky debt.

The Fed and IMF have both rung the alarm bell over the issue. In a worst-case scenario, a fund suffering large outflows as bond or loan prices fall will have to halt redemptions, trapping capital and potentially leading to an unwinding of the fund. Investors nervous about a potential issue will probably head for the exit early, making things worse for those who wait behind.

The fact that spillovers were seen in high-grade parts of the US credit market when pension funds in the UK were hit with margin calls has intensified concerns, given so many investors have piled into illiquid bonds and loans.

The rise of private credit has also opened the door to new issues, with policymakers and regulators warning they have little insight into the cottage industry. These debts are traded far less frequently — if at all — and are not marked consistently by creditors. Even with the debt sitting in funds that require longer capital commitments, it is unclear how endowments and pensions might try to sell their stakes in a crisis. The secondary market is still nascent, albeit growing.

“We will see a breakdown in private markets,” Stokes at Loomis Sayles added. “Every pension and endowment has shifted into [them].” Eric Platt

Emerging market defaults

Two risks threaten financial stability for emerging market investors.

The immediate fear is of multiple defaults among low and middle-income countries as high interest rates and the strong dollar make it harder to service dollar debts.

Credit rating agencies say 26 developing countries, about a third of those with sovereign eurobonds, are at substantial risk of default, extremely speculative, or in default.

Even so, the exposure of investors is less concerning. The 15 countries with bonds trading at distressed levels in October made up just 6.7 per cent of the benchmark JPMorgan EMBI sovereign eurobond index.

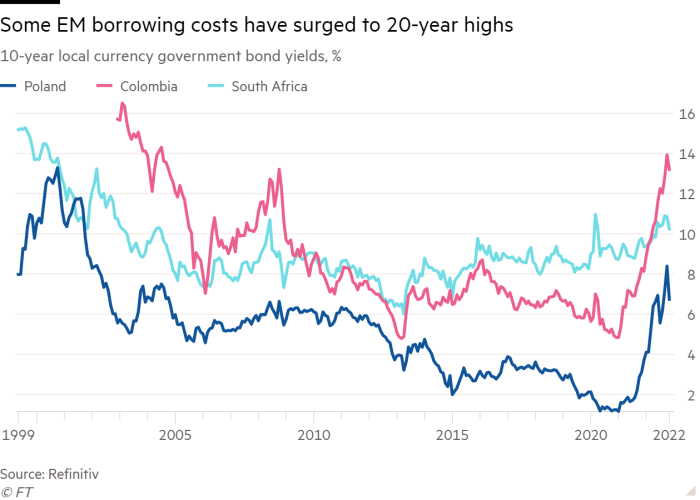

But investors have become unwilling to fund governments of some larger emerging economies. Yields on the domestic 10-year bonds of Poland, Colombia and South Africa recently hit 20-year highs. They and other issuers are being hit by soaring inflation or big fiscal imbalances, or both. Investors worry that economies will not grow quickly enough for governments to stop debt ratios rising out of control.

Poland’s yields peaked at 9 per cent in October. Its ratio of government debt to gross domestic product is about 55 per cent. That looks unproblematic next to Brazil, where comparable yields are 12 per cent and government debt to GDP is close to 90 per cent. Yet Brazil’s yields have been broadly stable for the past 15 years.

Investors are shunning Poland because its debt is of short maturity, about four years on average. But nerves about the landing point of inflation and interest rates, assuming they fall from their current highs, could quickly spread.

“There is no magic threshold at which [such debts] become problematic,” said Manik Narain, emerging market strategist at UBS. “But they force austerity on governments and can lead to capital flight.” Jonathan Wheatley