Every winter we hear about soaring energy bills and people’s inability to stay warm. But, until now, we haven’t really known just how cold Australian homes are. Our newly published research suggests around four out of five of Australian homes fail to meet World Health Organization minimum standards for warmth.

Australia has a reputation for being a hot place. It might lead us to think we just need to tough it out through winter, because soon it will be hot again.

Our winters may not be as cold as in Europe and North America, but our health statistics are a wake-up call. Our winter death rates are over 20% higher than in summer.

Newly updated building codes, and our health and welfare systems, assume most people are OK over winter. This is simply not the case. We need to take winter more seriously.

What did the study find?

About six years ago, we wondered just how cold Australian homes were. Over the past few winters, we have been measuring people’s in-home temperature. Our latest research suggests more than three-quarters of Australian homes were cold last winter – having an average winter temperature less than 18 degrees (the World Health Organization’s recommended minimum) during occupied, waking hours.

This is startling. Previously, it has been thought that only about 5% of people were cold.

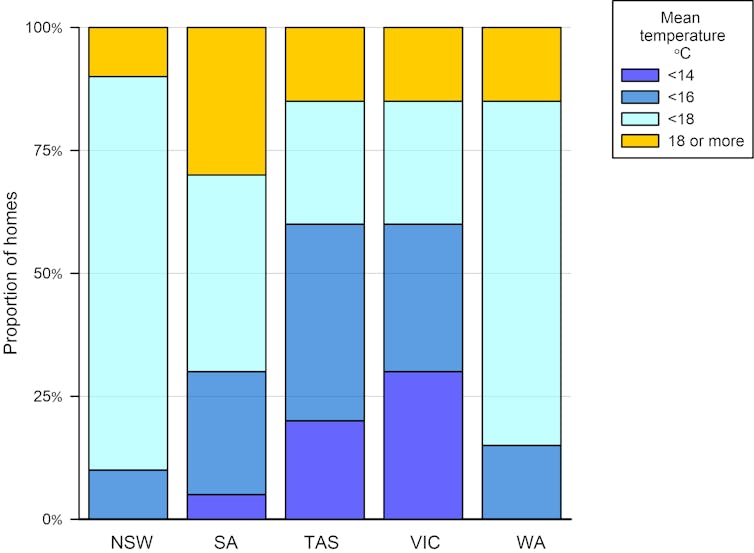

For our study, temperature sensors were placed in 100 homes across temperate New South Wales, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia. Two-thirds of Australia’s population live in these temperate climate zones.

Across the sampled homes, 81% were below 18°C on average across the whole of winter. The homes averaged 16.5°C across occupied, waking hours. The coldest homes had a minimum hourly average of just 5°C.

Tasmanians were hardest hit. Some homes in this state had average indoor temperatures of less than 11°C.

But, regardless of state, the majority of homes in our study were unhealthily cold.

Read more: Forget heatwaves, our cold houses are much more likely to kill us

Who’s at risk?

Cold isn’t just a problem that affects low-income households. The research included homes that were owned outright, mortgaged and rented, across all income levels.

Some people might feel comfortable at 16℃, but many are not cold by choice. A combination of poor housing conditions, inadequate heating and not being able to afford the cost of heating leaves many struggling to stay warm. And energy prices are set to rise.

The aged, people with a disability and those facing housing insecurity are most at risk. This includes those struggling to pay rent, moving frequently, living in overcrowded homes or spending most of their income on housing. There are also greater challenges for renters.

Cold indoor temperatures can make other problems such as mould worse, and can even affect our mental health.

We must recognise the connection between health and cold housing. The objectives of housing and health policies must be linked to improve the situation.

Australia is shifting towards providing more home-based care, rather than hospital care. This trend means we must be even more careful to ensure home environments are healthy.

There is also a need to increase community awareness of the risks of cold housing. At-risk groups include First Nations communities, the aged, the young, disabled and those in insecure housing.

Delivering healthier housing is one of the best ways of raising the living standards and quality of life of these communities.

Read more: What is hospital in the home and when is it used? An expert explains

We can learn from successes overseas

New Zealand and the United Kingdom have been tackling cold housing with remarkable success. Both have started by acknowledging a collective social responsibility to address this problem.

We, too, must realise the problem is bigger than individual households. National ownership of this problem and a systemic response are required.

The NZ and UK interventions have started with rentals, both government and private. Their experience shows mandatory requirements to protect tenants, in particular, need to be made transparent and objective.

With almost one-third of Australians renting their homes, such actions could improve the lives of millions of people.

Both NZ and the UK used housing surveys to track progress in housing quality over time. This method clearly shows what works best and identifies areas that still need improvement.

Similarly, Australia should closely monitor progress towards housing that keeps temperatures at a healthy level. Results should be made public. This would promote continued improvement of housing conditions and help direct investment to policies that deliver the best results.

Importantly, we need to keep providing robust research on who is most vulnerable. Our study represents early data from a bigger study of 500 homes, which will enable us to more conclusively identify the true risk of cold housing in Australia.

Cynthia Faye Barlow receives funding from National Health and Medical Research Council grant number 2004466.

Emma Baker currently receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), The Australian Research Council (ARC), the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), and the Environment Protection Authority Victoria.

Lyrian Daniel receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), The Australian Research Council (ARC), and the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.