From the 1980s into the early 2000s, nonunion construction contractors that resisted union organizing efforts by Operating Engineers Local 150 in the Chicago area and beyond kept finding heavy machinery sabotaged at their work sites.

Acid was poured into engine parts. A bulldozer and a front-end loader were launched into a quarry. Pipe bombs were set off at an asphalt plant.

In one incident, 100 or more people stormed a nonunion work site, and equipment “was shot and set on fire, windows were broken, tires were slashed and a job trailer with three men inside was tipped over,” according to authorities.

In a 1999 Chicago Sun-Times interview, William Dugan, the since-deceased leader of Local 150, said his group wasn’t behind any vandalism and suggested that the contractors were damaging their own equipment for the insurance money and blaming an easy target.

“It would be ludicrous for us to picket a contractor, then do some damage to that owner’s property,” Dugan said. “We don’t resort to that stuff.”

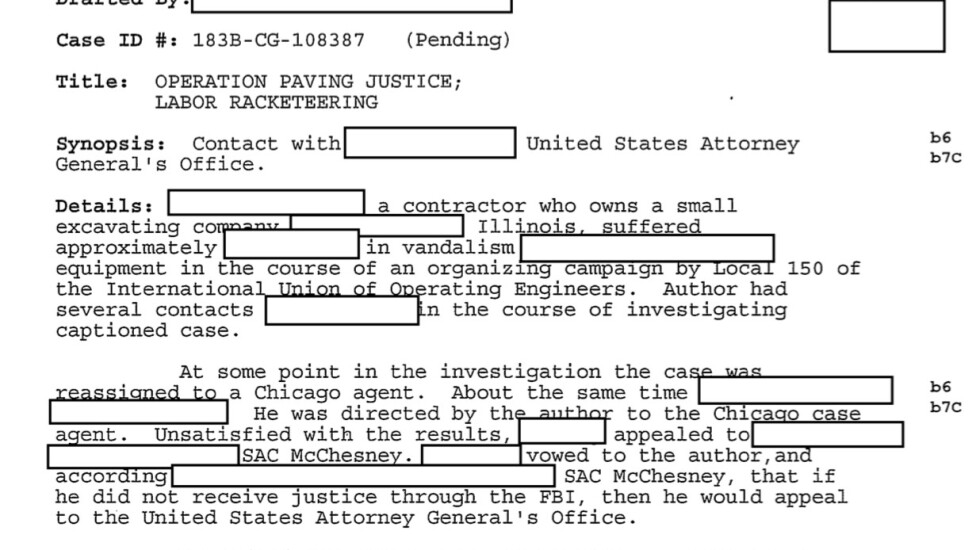

But the vandalism and violence prompted federal agents to open an investigation in 1998 into Local 150, according to Dugan’s FBI file, recently obtained by the Sun-Times. The investigation, dubbed Operation Paving Justice, lasted six years before it was shut down in 2004 without any criminal charges being filed, though investigators estimated there had been $70 million in “equipment and property” damage.

Union officials say the investigation didn’t result in charges because the labor group wasn’t to blame.

“This six-year, multi-office investigation was terminated nearly 20 years ago . . . due to a lack of evidence,” a Local 150 spokesman says. “No charges were ever filed as a result of this investigation, and we emphatically deny any suggestion that Local 150 was involved in the activity that was being investigated.”

Also, he says, “Nowhere in these documents are any current staff members of Local 150 mentioned or connected with any activities that were being investigated.”

At the time, Dugan’s FBI file shows, an official in the office of the U.S. attorney general — which had been contacted by someone, possibly one of the contractors — asked an FBI agent “if the FBI investigated the case to the best of its abilities, and if every incident and possibility was investigated,” according to a 2003 FBI memo.

The agent “opined that the case was not investigated adequately, and that further investigation of the case was not endorsed by FBI supervisors,” the memo said.

When the investigation was shut down in 2004, another FBI memo, labeled “Case Closing,” said: “All investigative leads have been exhausted regarding past incidents of Local 150. Concerning the most recent incident occurring in northern Indiana, [the FBI] Chicago Division’s attempts to obtain U.S. attorney’s office authority to conduct a consensual recording between a cooperating individual and a Local 150 business agent failed when” a prosecutor “declined to grant authority to record.”

The same memo said, “The various Local 150 tactics should be appropriately investigated as state offenses” because “such conduct in and [of] itself did not amount to a federal violation.”

An earlier portion of the Dugan FBI file, from 2000, said the investigation involved possible violations of the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, perhaps best known for its use in taking down the mob: “Chicago’s investigation centers on violation of the Federal RICO statute using the State of Illinois intimidation statutes or any other predicate offenses of the RICO statute.

“Since the captioned case was opened, numerous victims have been located across Illinois and into the northern counties of Indiana.

“Each victim has had virtually the same experience. At some point during the non-union contractor’s labor dispute with Local 150, the contractor’s equipment is damaged. The damage is usually the result of acid or some other substance being placed in the equipment’s hydraulics. The damage amounts have ranged from as little as $1,000 to as much as $500,000 or more per incident.

“Some of the non-union contractors have opted to accept the union contract and the vandalism seems to cease once the contractors sign with Local 150.”

Members of Local 150 — based in Countryside and representing workers across northern Illinois and parts of Indiana and Iowa — operate and maintain heavy equipment “in a variety of industries, mainly tied to the construction industry,” according to the union, which says that, under Dugan’s leadership, the group “doubled its membership from about 10,000 in 1986,” when Dugan became boss, “to over 22,000 members in 2008,” when he retired.

Harnessing the clout of his members as a voting bloc, Dugan wielded a political fund that contributed to members of both major political parties, some of them in positions to have a say on government-funded road work and other infrastructure projects.

Dugan, who died in 2020, was appointed by successive Illinois governors to government boards and commissions with authority over taxpayer spending and policy decisions. They included the Illinois Gaming Board and the governing boards of the CTA and the Illinois State Toll Highway Authority, where Dugan secured “the first significant multi-project labor agreement in Illinois, guaranteeing all tollway construction work would be performed by union contractors,” according to a union biography.

Dugan’s successor James Sweeney, who’s still in charge of Local 150, is also a member of the tollway board, reappointed in 2019 by Gov. J.B. Pritzker. Sweeney, who, according to the union, was hired by Dugan in 1987 as Local 150’s first full-time organizer, wouldn’t comment on the closed FBI investigation.

The FBI will release, on request, some or all of its files on people who have died. In releasing Dugan’s file, it redacted parts of some records and withheld others entirely.

The material it released offered glimpses of Local 150’s ties to political figures and police.

For instance, one portion of the files discusses the 1986 arrest of a union member in the southwest suburbs in the incident in which the trailer was flipped and those charges being dropped by a Will County prosecutor.

According to an FBI document, the member, whose name was blacked out, “was arrested and charged with armed violence, arson and mob activity.”

The Will County state’s attorney’s office “dismissed the charges without [name blacked out] ever having the chance to testify,” the document shows. “That former state’s attorney is now a state senator who has enjoyed generous financial backing by Local 150 and its members.”

The same document says: “Throughout the course of other investigations into activity by Local 150, witnesses have changed their stories, suddenly refused to cooperate, and one key witness in a bombing investigation allegedly committed suicide shortly before the trial. One man who testified against members of Local 150 in a civil matter awoke one morning to find [blacked out].”

According to another document in Dugan’s FBI file: “Local 150 [blacked out] admitted to the case agent that law enforcement officials run license plate numbers for Local 150 members to identify addresses of non-union contractors or other individuals in whom Local 150 has an interest.”

Agents interviewed three suburban police chiefs about that, according to the records.

Federal authorities later opened another investigation into Dugan. In that case, he pleaded guilty in 2010 to using his union post for personal gain and was sentenced to probation.