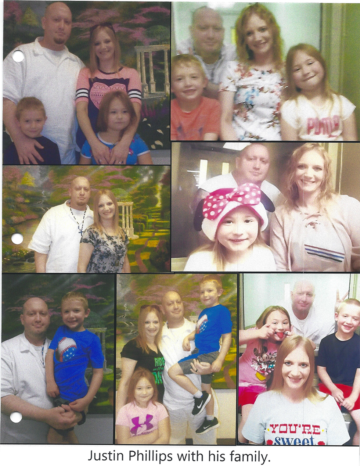

Justin Phillips’ health started deteriorating soon after police arrested him on drug charges in 2016. He grew gravely ill while waiting for his court date at the Smith County jail in Tyler, and doctors diagnosed him with kidney disease. Now, after serving more than 3 years of his 10-year prison sentence, Justin suffers from end-stage renal failure.

Justin, 40, and his wife, Casey, cited both his declining health and the progress he’s made behind bars in letters asking for his release on parole. During his time in lockup, Justin has successfully finished a gang-renouncement program, completed substance abuse counseling, and reconnected with his 7-year-old son, who now visits him regularly. “I am determined not to let my past define me, and I’m eager to prove I am a better person, and I’ve learned from my mistakes,” Justin wrote to the Texas Board of Pardons and Parole last September. “I want an opportunity to be a present and active father and husband to my family, as well as a productive member of society.”

Officials denied Justin’s parole in early March, but he and his wife are begging officials to reconsider: COVID-19 poses a particular threat to him and other prisoners whose health is already failing. “There are honestly times where I fear whether he’ll make it out alive,” Casey told me. “If he gets sick, it’s possible I may never see my husband again.”

Calls for the compassionate release of sick and elderly people incarcerated in Texas have increased since the first coronavirus cases were confirmed behind bars in the state. Last week, a Texas prisoner and a medical staffer at a prison hospital in Galveston both tested positive for COVID-19, as did a correctional officer at the Segovia Unit in Edinburg, a substance abuse counselor at the Jester 1 Unit in Richmond, and another prison staffer at the Holliday Unit in Huntsville. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) has temporarily halted prisoner transfers from the Dallas County jail after several inmates there tested positive for the virus. On Monday, TDCJ announced that another prisoner and two parole board employees had also tested positive for COVID-19.

Public health experts, defense attorneys, and even some prosecutors have warned that the crowded and unsanitary conditions behind bars make correctional facilities a ticking time bomb. As a result, authorities across the country have begun releasing inmates to try and prevent the spread. Last week, 14 senators from both parties sent a letter to the Justice Department petitioning for the release of elderly, terminally ill, and low-risk inmates in the federal prison system.

While sheriffs in charge of county jails across Texas are flagging low-risk inmates for release and begging local police to stop jailing people for petty charges, state officials have taken no similar action to decarcerate Texas prisons. Two weeks ago, advocates for incarcerated people sent Governor Greg Abbott a list of recommended steps to lower the state prison population, including releasing more parole-eligible people who are elderly or have chronic illnesses.

Not only has Abbott ignored those recommendations, on Sunday he issued a sweeping executive order limiting what local counties can do to reduce their own jail populations. Abbott’s order, which bars jails from releasing inmates who can’t pay bail and who are accused or have previously been convicted of violent crimes, came on the same day the Harris County jail reported its first case of an inmate testing positive for COVID-19.

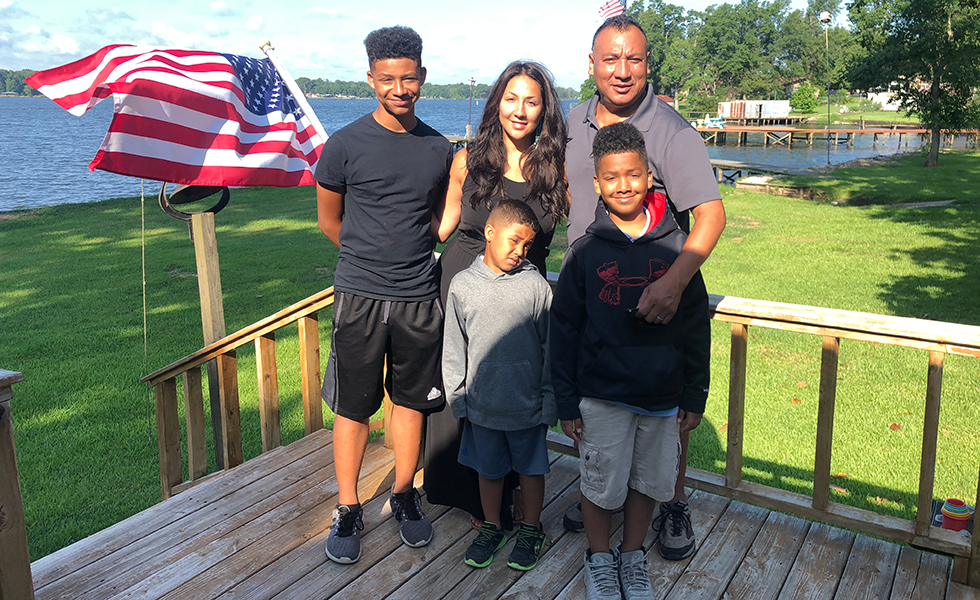

In addition to expediting the release of sick and elderly prisoners who are eligible for parole, advocates for incarcerated people have also asked for the release of people like Arturo Rios, 55, who made parole in October. Rios, who went to prison for a felony DWI conviction, says he suffers from several serious medical problems—including complications from a previous spinal fracture—that have weakened his immune system and made him susceptible to infections, colds, and flu. “I am afraid since I am very vulnerable to infection and sickness,” Rios wrote to me in a recent letter from the Hamilton Unit in Bryan.

Rios’ release is contingent upon him completing a six-month substance abuse treatment program, which he’s slated to finish next month. TDCJ insists such classes will continue; however, Rios told me there are already fewer counselors for his program after the prison system began reporting coronavirus cases. Both Rios and his daughter Andrea McMillian have asked prison officials to release him as soon as possible, so far without luck.

“I wasn’t so worried before, but now with coronavirus, I’m calling everyone I can find,” McMillian told me. “He was basically in bad shape going in, and since then has deteriorated tremendously.”

While TDCJ has taken precautions to limit the spread of coronavirus, like temporarily barring inmate visits, people inside complain of squalid conditions that they say are now an emergency in light of the pandemic. Last week someone incarcerated at the Allred Unit near Wichita Falls sent me a grievance he filed with officials claiming inmates aren’t given daily showers or cleaning supplies; he also wrote that some are forced to live in cells where “dried blood and other bodily fluids are left behind.” On Monday, two elderly prisoners at the Pack Unit near Navasota sued TDCJ, alleging that prison staff aren’t even following the “grossly inadequate” coronavirus precautions. For instance, the prison still hasn’t posted signs throughout the facility to warn inmates about the risk of the virus.

Justin Phillips says he hasn’t seen those signs, either. He and other inmates incarcerated at the Estelle Unit near Huntsville have mostly learned about coronavirus by crowding around the TV to hear news reports. “It seems like they’re hoping it doesn’t come here, just crossing their fingers,” he told me in a recent phone call from prison.

Justin says whatever life he’ll have after lockup has already been shortened because of the medical problems he’s faced in prison. He fears he’ll never have a life outside if he catches COVID-19. “If I get coronavirus, the chances of me fighting it off are not good,” Justin told me. “They could be giving me a slow death sentence, that’s how it feels—not the 10-year sentence I was given by the judge.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that Justin Phillips is incarcerated at the Ellis Unit. He is at the Estelle Unit. The Observer regrets the error.

Find all of our coronavirus coverage here.

Read more from the Observer:

-

In a Pandemic, Poor Defendants Could Pay With Their Lives: COVID-19 lays bare the fundamental inequalities that a cash bond system creates, and highlights the unsafe conditions our jails and prisons have designed.

-

In Migrants Camps Along the Texas-Mexico Border, Close Quarters and Closing Borders Raise Concerns: Advocates and lawyers warn new measures implemented along the southern border in response to COVID-19 are putting vulnerable migrants at higher risk.

-

The New U.S. Food Safety Czar is a Texas Researcher with Close Ties to the Meat Industry: Mindy Brashears’ confirmation comes at a time when Americans are scouring supermarket aisles for safe food to eat.