“…when you’re shooting a film like Magic Mike, and you’re doing dance routines for two weeks at a time, you have to peak every day. So that became kind of crazy. We had a gym in the parking lot, and we’d all be lifting weights on set all day,” explained actor Joe Manganiello, about performing in the film Magic Mike.

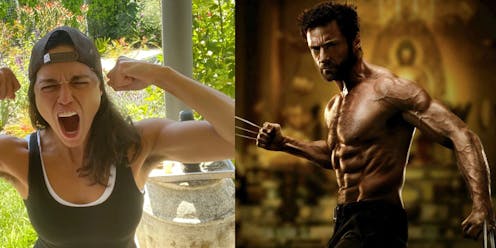

It is not unusual for actors to undergo drastic changes in preparation for a role, including gaining muscle and losing body fat for that shredded look. In fact, this is becoming the norm in Hollywood.

Jake Gyllenhaal in Road House, Michelle Rodriguez in Dungeons & Dragons, and Paul Rudd in Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania, have all undertaken body modifications for roles this year.

As the audience, we readily accept these body modifications to be part of the preparation for the role without necessarily considering the potentially long-term physical and mental health consequences.

So how do they do it?

From what Hollywood shares with the general public about these body modifications, which is generally very limited, it appears these transformations occur through excessive exercise and highly restrictive diets.

Nevertheless, these Hollywood workouts are highly popular with ordinary people, with Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson and Chris Hemsworth’s workouts particularly sought after.

These regimens resemble those of competitive bodybuilders, whose success also relies on appearance.

The typical process for bodybuilders involves two phases: a “bulking” phase, during which the goal is to have enough energy for muscle growth, and a “cutting” phase, when the aim is to lose weight but not muscle.

The end result of such a process is usually highly applauded, even though drastic measures have been taken to achieve such a look.

Actors of all genders are undergoing these body transformations for various roles such as superheroes, athletes, or the portrayal of real-life people.

What are the consequences?

“I’ve become a little bit more boring now, because I’m older and I feel like if I keep doing what I’ve done in the past I’m going to die. So, I’d prefer not to die,” said Christian Bale, who has undertaken multiple extreme transformations for roles.

To achieve what is needed for a particular role, extreme measures are often taken. However, the consequences of these measures, such as use of substances, exercise dependence, and an increased risk of developing muscle dysmorphia and/or an eating disorder, is seemingly not common knowledge.

A concern for the bodybuilding community is the widespread use of drugs, often multiple drugs at a time not obtained through prescription. Androgenic-anabolic steroids are commonly used which can have extensive negative effects on the human body, including on the cardiovascular system, hormones, metabolism and even psychiatric wellbeing.

Exercise dependence can also occur when an individual engages in an extreme amount of exercise, to the point at which physical, psychological or emotional harm can occur. We are not sure exactly why exercise dependence happens, but it could potentially be a form of behavioural addiction.

Another risk is muscle dysmorphia, a subtype of body dysmorphic disorder characterised by the individual being preoccupied with the idea their physique is not muscular enough, even if they have a high degree of muscle.

What about the dieting impacts?

There are many similarities between the requirements of bodybuilding and eating disorders. Both are characterised by restrictive diets, high levels of exercise, potential social isolation, and adherence to a rigid schedule.

The seminal Minnesota Starvation Experiment fundamentally shaped our understanding of the changes a person can experience when they are consuming less than their daily nutrition energy needs, such as during the “cutting” phase for bodybuilders. This research showed that people who are experiencing starvation for a period of time will experience devastating impacts in the physical, psychological, behavioural and social aspects of their lives.

Some of the many documented changes included reductions in heart muscle mass, heart rate and blood pressure, dizziness, fatigue, increased feelings of depression and anxiety, obsessive thoughts about food, and withdrawal from social activities and relationships.

Concerningly, even once a person is renourished, the psychological issues around body size and food can persist. Therefore, even after an actor has returned to their pre-modification weight and size, it does not mean they have recovered from the consequences that came with that body modification.

What are the impacts on the general public?

Rapid changes in physical appearance are not realistically achievable for most people. So seeing actors doing this seemingly easily with the assistance of their professional teams sets an unrealistic standard.

For people without the same income or access to resources to achieve these body modifications in a safe way, more extreme means would be undertaken and consequent damage to mental and physical wellbeing can ensue. These body modifications are definitely a case of “do not try this at home”.

There are many risks when undertaking dramatic body modifications, most of which are not talked about in public. Actors are just as vulnerable to these risks, despite us rarely seeing what exactly they go through to achieve these dramatic transformations. Hollywood is a highly competitive environment, and being honest about body modification and its consequences could stop an actor landing their next gig.

We don’t recommend body modifications in any way, but if someone does want to make a change to their lifestyle, we strongly recommend consulting with a team of health professionals to ensure physical and psychological safety during the process and beyond.

––

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, do not hesitate to reach out for support. For concerns around eating, exercise, or body image visit the Butterfly Foundation or call the national helpline on 1800 33 4673. For concerns around drug use visit Drug Help or call the National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline on 1800 250 015.

Gemma Sharp receives funding from an NHMRC Investigator Grant (Emerging Leadership 2).

Bronwyn Dwyer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.