Do you buy plants online? You might be breaking the law without even knowing it.

We found hundreds of different invasive plants and prohibited weeds advertised on a popular online marketplace.

For the first time, our research has exposed the frequent, high volume trade in pest plants across Australia.

State and territory governments are adopting our automated surveillance approach to help regulate the online trade in plants and other wildlife. Biosecurity officers can receive automatic alerts for suspected illegal trade, rather than manually monitoring websites or relying on reports from the public.

What’s the problem and why all the fuss?

Certain plants are prohibited in Australia because they are harmful to our unique natural environment and agricultural industries. These weeds can threaten native species, fuel severe fires and choke rivers.

Weeds are also a social and cultural threat for First Nations people, because they can compete with traditional food and medicine plants, causing them to decline.

Overall, invasive plants are estimated to have cost Australia A$200 billion since 1960.

Weeds that are controlled under state and territory laws are referred to as “noxious” or declared plants. Each state and territory has different laws prohibiting the sale and cultivation of these declared plants.

Compliance is generally high within the horticultural industry, save for the occasional high profile blunder. The main problem for Australia is the widespread invasive plant trade on public online marketplaces.

Trade of ornamental plants, which are the kinds popularly grown in homes and gardens, is the major current pathway enabling invasion and spread of weeds into new areas. They’re travelling long distances, to homes in new places.

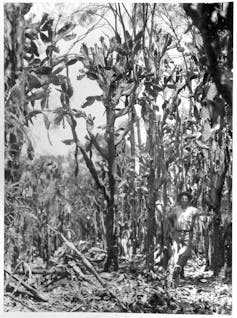

Invasive cacti and ornamental pond plants are among the most frequently advertised plants, but many are banned from sale and distribution in Australia.

Internet trade has historically been tricky to monitor and regulate, which has led to a variety of invasive species being widely traded.

Scraping the web

We used specialised software called “web scrapers” to monitor trade on a public classifieds website. These automated web tools can be used to rapidly harvest information from advertisements. This allowed us to detect thousands of advertisements for weeds over a 12-month period.

We found 155 declared plant species traded on one website, and we suspect there could be more.

Prickly pear cacti were among the most frequently traded declared plants. This is concerning given their history in Australia. In the 1920s, about 25 million hectares of land became unusable due to prickly pear invasion.

Aquatic weeds were another popular group. That includes water hyacinth, which is the world’s most widespread invasive alien species according to a recently published global assessment.

We found some sellers advertised uses for the declared plants they were trading, including for food and medicinal properties.

Aquatic weeds were often stated to have water-filtering properties and provide habitat for fish. Those traits make Amazon frogbit a popular choice for aquariums and ponds, but if the weed enters creeks and rivers it can have devastating consequences.

Everyone can do their bit

Better surveillance is not the only solution. Public awareness is key to reducing invasive plant trade. We can all make informed decisions about the plants we buy.

A significant hurdle is a phenomenon called “plant blindness”. People tend to find plants harder to recognise than animals. We found many weeds sold using generic names such as lily, cactus or pond plant. Some people may not even know the true identity of a plant they are selling, let alone that it is a weed and illegal to trade.

Another complication is the fact that laws differ between states. Plants that might be legal for an interstate trader, might still be illegal for you to buy. This is why caution should be taken when sending or receiving plants by post. Always check your local regulations before buying or selling a plant online. You can find out what is declared on your state or territory’s biosecurity website or on Weeds Australia.

Online marketplaces must also cooperate with local policies. These platforms should be enforced to self-regulate trade and include measures to prevent illegal advertisements from being posted in the first place. Failure to act may result in significant penalties from governments. Last year the Brazilian government fined Meta for failing to remove illegal wildlife trade from Facebook and WhatsApp.

For now, monitoring tools such as the web scrapers we have developed will help to prevent some weeds escaping backyards and into bushland. As plant lovers, it’s important to be mindful of the plants we choose to buy and keep.

Read more: Lickable toads and magic mushrooms: wildlife traded on the dark web is the kind that gets you high

Jacob Maher receives funding from the Centre for Invasive Species Solutions.

Phill Cassey receives funding from the Centre for Invasive Species Solutions and the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.