The story so far: For five years, the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Madras has maintained its dominance as the top-ranked higher-education institute in India. Other IITs follow suit, holding seven out of the top 10 positions in the ‘Overall Category’ of the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) 2023, released this week. The Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bengaluru, All India Institute of Medical Sciences in Delhi (AIIMS) and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) have also been consistently placed in the top 10.

The eighth edition of NIRF, released by the Ministry of Education, is an assessment of universities and colleges in India, evaluating institutions on weighted variables: student strength, faculty qualifications, infrastructure and the number of economically and socially deprived students. The NIRF rankings come amid concerns surrounding caste discrimination and lack of mental health infrastructure in top-ranking institutes. IIT Madras saw a fourth case of student death by suicide in April, while Darshan Solanki’s death at IIT Bombay raised questions about institutionalised caste discrimination.

The Hindu digs into the takeaways from this year’s rankings, the methodology used and why the framework has come under scrutiny over the years.

How does NIRF work?

India has 1,113 universities, 43,796 colleges and 11,296 stand-alone institutions, according to the India Survey on Higher Education. Out of these, 5,543 unique institutions (9.86% of the total) participated in the ranking exercise across 13 categories — ‘overall’, universities, medical, engineering, management, law, architecture, colleges, research institutions, pharmacy, dental, agriculture and allied sectors, and innovation.

Launched in 2015, NIRF was meant to “follow an Indian approach that considers India-centric parameters like diversity and inclusiveness apart from excellence in teaching and learning and research,” then-Minister for Human Resource Development Smriti Irani had said. Anil Kumar Nassa, Secretary of the National Board of Accreditation, while releasing this year’s rankings, noted that NIRF addresses the limitations of international rankings, which may not account for region-specific context.

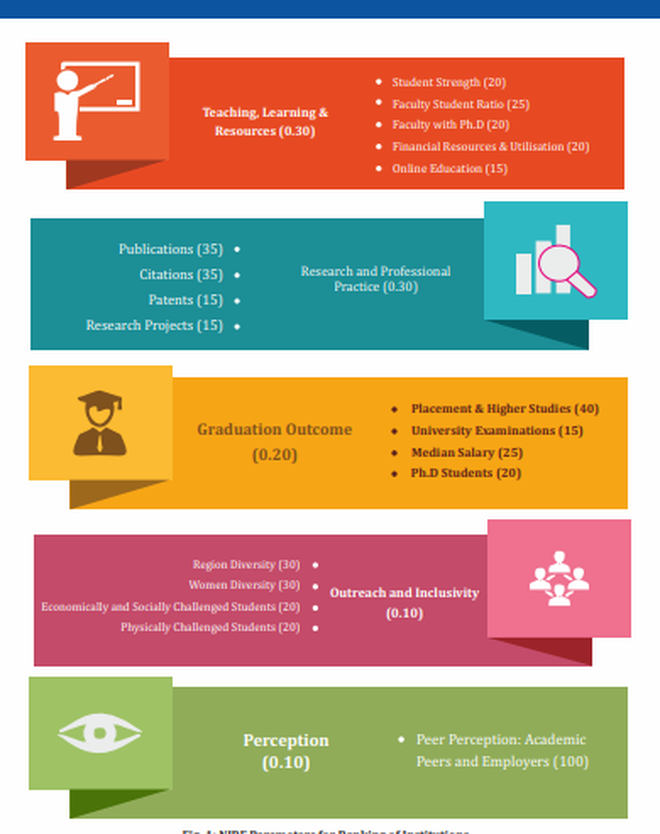

The higher education institutes were evaluated across five parameters, weighted differently: Teaching, Learning and Resources (TLR, 30%); Research and Professional Practice (RP, 30%); Graduation Outcome (GO, 20%); Outreach and Inclusivity (OI, 10%); Perception of the institute (10%). Each parameter has a sub-category. For the total 100-mark OI score, the four sub-parameters are students from other states/countries (30), women diversity (30), economically and socially challenged students (ESCS, 20), facilities for physically challenged students (PCS, 20). The representation of students from marginalised locations is thus given 2% weightage in the overall ranking.

Registered institutions self-submit required documents online; data on patents, research and citations were retrieved from third-party websites such as Scopus. NIRF invited feedback from stakeholders through public announcements for a period of one week, post which the data was analysed and a survey was undertaken. Participating HEIs are required to upload this data on their own websites in the interests of transparency. Experts, however, have noted that some private multi-discipline universities failed to grant free access to such data on their websites, requiring additional details of the person seeking this data.

2023 findings at a glance

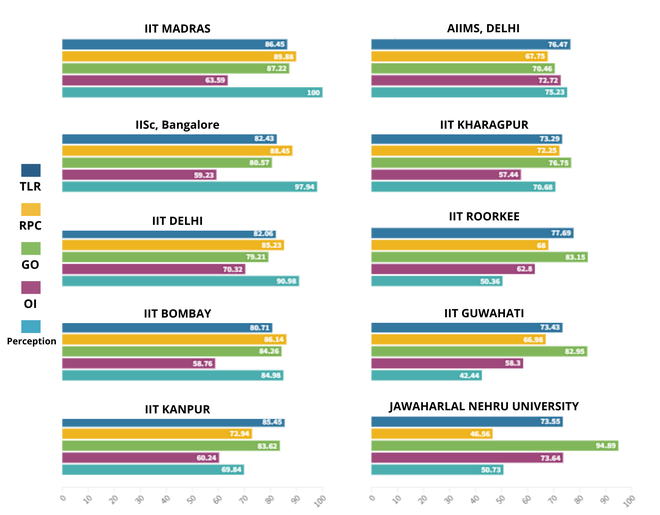

The top 25 ranks have remained mostly undisturbed over the years, with IIT Madras and the IISc Bengaluru retaining the top positions. IISc falls behind IIT Madras across metrics of online education, research and patents, and representation of economically and socially disadvantaged students. In comparison, the international metric QS Global World Ranking 2023 (by education think-tank QS Quacquarelli Symonds) titled IISc as India’s top university, followed by IIT Bombay, Delhi and Madras.

“...although individual ranks might have changed by a few slots for some institutions due to performance variations across institutions on some of the parameters. This demonstrates that the set of parameters that are being used for ranking are compact, coherent and inter-dependent,” the 2023 report states. The top 10 colleges in the “overall” category, for instance, are the same as last year, with some switching places (IIT Bombay, IIT Kharagpur and IIT Roorkee dropped marginally, while AIIMS Delhi rose from 9th to 6th place).

36 institutes of the “overall” category were Institutes of National Importance (INIs, such as IITs and NITs), 26 are State universities, and seven Central universities were in the top 100 HEIs. Unlike previous years, State-sponsored colleges and universities outnumber Central HEIs in the medical vertical.

State-wise break-up

NIRF this year introduced the “agriculture and allied sectors” and “innovation” categories, with Indian Agricultural Research Institute and IIT Kanpur topping the two verticals respectively.

Why have experts criticised NIRF?

While NIRF is a good beginning for India to piece together the state of education, the parameters and metrics used “lack scientific merit”, says Professor Krishna Raj of the Centre for Economic Studies and Policy.

The first concern is the small radius of participating institutions in the voluntary exercise — accounting for less than 10% of the total HEIs — which makes NIRF a narrow, inconsistent and sometimes contradictory representation of India’s higher education landscape. For instance, in last year’s rankings, Symbiosis Law School (a private law college) scored a 100 in Perception, surpassing National Law Universities which are a popular choice for law aspirants.

The limited representation could be because there is no compulsion or incentive for institutes to participate, says Professor Raj. NIRF’s inclusion guidelines could be another reason; these permit registration for institutes with a minimum of three batches, a defined faculty-to-student ratio and at least 1,000 students enrolled for UG and PG courses for entry into the “overall” category.

Categorise-wise top 3 colleges

Secondly, methods of teaching and evaluation vary , but the parameter for comparing HEIs in the “overall ranking” is the same for all institutions, which can be a bit “confusing”, says Professor Raj. While data on publications, patents and research may apply to medical and engineering colleges, it remains unsuitable for social science institutes or law schools. Comparing a JNU with an IIT may be asymmetric when there are stark differences in research laboratories and graduation outcomes due to professional job markets, says Professor Raj. “Social science research institutions are then at a disadvantage in this ranking. IITs and IISc grab more points... they will be ranked higher.”

Moreover, the data collected is not granular enough for the results to translate into meaningful insights. For example, the rankings specify “faculty with PhD vs faculty with master’s degree”, but micro-level data on how many professors and assistant professors hold the degree, and how many marginalised students are enrolled in PhD courses, might have added more value— since University Grants Commission norms mandate PhD for most academic positions. Similarly, despite increasing education costs, the NIRF neither measures nor makes any mention of individual fees as a metric for evaluating institutes.

Self-reported data may also be overstated and fudged, allowing institutes to inflate their results. “Evidence suggests that some private multi-discipline universities have claimed the same faculty in more than one discipline. Faculty in liberal arts have been claimed as faculty in law too, to claim an improved FSR [faculty-student ratio]. This manipulation defeats the purpose of ranking, especially in the case of single-discipline institutions like the NLUs,” Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law professors wrote in The Hindu last year. In 2021, NIRF also changed its methodology for counting students in the ESCS category, including both UG and PG students who received full tuition-fee reimbursement from the institution.Moreover, the OI category allows greater weightage to regional diversity than ESCS students. Central universities like NITs and IITs, which cater to pan-India aspirants, may then fare well and score higher marks in that sub-parameter.

Professor Raj also flags that “social aspects and social justice aspect is completely missing in our national ranking system,” referring to only 10% weightage given to inclusivity metrics. A survey of 388 Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe students in February 2022 found 77 students describing in detail the kinds of caste-based discrimination they faced on campus.

SC/ST representation among faculty is also not considered, in spite of reports about the lack of representation and harassment faced by teachers from marginalised communities. Despite 1,439 vacancies in SC, ST and OBC categories between 2021 and 2022, only 449 recruitments were made. IIT Madras fared worse: it had only 19 faculty members from SC and ST communities, compared to the strength of 577 teachers from the Open Competition (OC) and OBC categories.