The story so far: The 2022 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to Swedish geneticist Svante Pääbo for his research in the field of genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution.

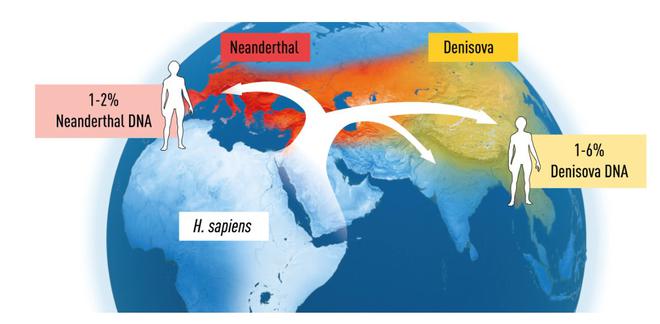

“Thanks to Svante Pääbo’s discoveries, we now understand that archaic gene sequences from our extinct relatives influence the physiology of present-day humans. One such example is the Denisovan version of the gene EPAS1, which confers an advantage for survival at high altitude and is common among present-day Tibetans. Other examples are Neanderthal genes that affect our immune response to different types of infections,” the academy’s citation read.

Dr. Pääbo’s research has resulted in the rise of a new scientific disciple called paleogenomics, which is the study and analysis of genes of ancient or extinct organisms.

The prize was announced on Monday by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm.

All about Svante Pääbo’s research

Dr. Pääbo’s groundbreaking research attempts to answer questions about human evolution. He was able to sequence the genome of Neanderthal, a species of humans that existed on the earth and went extinct around 30,000 years ago. He also discovered Denisova – a previously-unknown hominin. (Hominins are extinct members of the human lineage.) Dr. Pääbo’s research led him to the conclusion that “gene transfer had occurred from these now extinct hominins to Homo sapiens following the migration out of Africa around 70,000 years ago”.

This ancient gene flow has significant physiological relevance for present-day humans, The Nobel Foundation said in a press release.

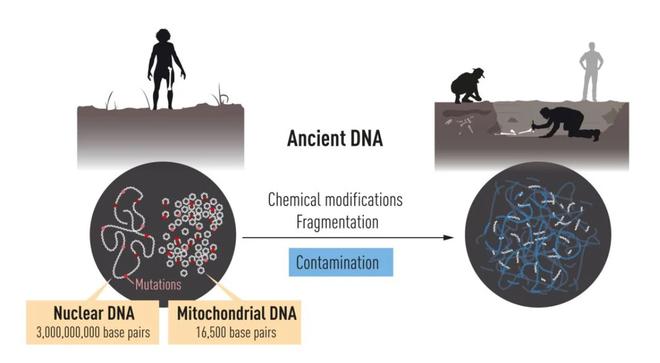

Dr. Pääbo was fascinated with the idea of studying the DNA of Neanderthals from early on in his career, but it was not an easy task. Over time, DNA tends to degrade and become chemically modified. Since Neanderthals became extinct 30,000 years ago, only trace amounts of their DNA would have been left in fossils, if any.

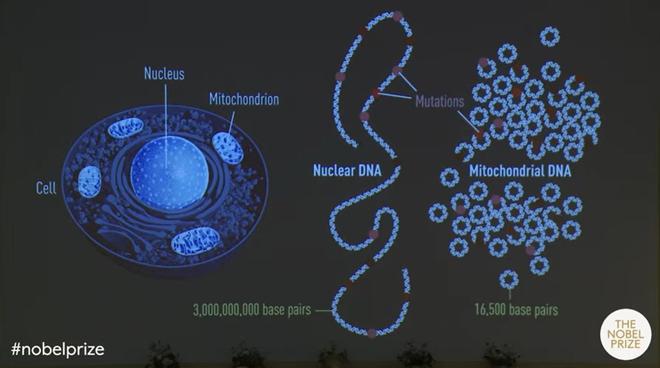

Dr. Pääbo was appointed as a professor at the University of Munich in 1990, where he continued his research to study DNA from extinct human species. This was when he decided to study mitochondrial DNA from Neanderthals. Mitochondria, popularly called the powerhouse of the cell, is an organelle inside the cell that has its own DNA. Although the mitochondrial genome is small and only contains a fraction of genetic information in the cell, it is present in thousands of copies. This increases the chance of its successful sequencing.

The geneticist was successful in sequencing a part of mitochondrial DNA from a 40,000-year-old bone. A comparison of this with contemporary humans and chimpanzees showed that Neanderthals were genetically distinct.

Moving forward in his career and genetic research, Dr. Pääbo was offered the chance to set up the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, where he is currently the director. At the institute, Dr. Pääbo and his team continued to improve the methods they used to analyse DNA.

In 2010, he published the first Neanderthal genome sequence.

DNA sequences from Neanderthals were also found to be more similar to sequences from contemporary humans originating from Europe or Asia than to contemporary humans originating from Africa, suggesting interbreeding between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens during their coexistence.

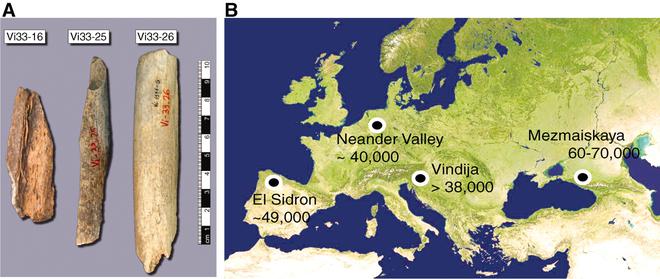

Dr. Pääbo published a research paper in 2010 on a draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome. In the paper, he outlined his team’s analysis of 21 Neanderthal bones from Vindija Caves in Croatia. Bone powder from these specimens was analysed and three bones were selected for further analysis.

Nine DNA extracts were prepared from the three bones. DNA and microbial contamination were factored in before continuing with the investigation.

Five present-day human genomes from different regions – one San from Southern Africa, one Yoruba from West Africa, one Papua New Guinean, one Han Chinese, and one French from Western Europe – were sequenced and analysed against the Neanderthal genome derived from the experiment, to put divergence in the DNA of the two into perspective. It was noted that the divergence of the Neanderthal genome to the human reference genome was greater than for any of the present-day human genomes that had been analysed.

The Neanderthal genome allows researchers to identify features that are unique to present-day humans, relative to other hominins.

What do we know about Neanderthals?

Neanderthals, the closest relatives of the present-day human species, lived in Europe and West Asia – as far as southern Siberia and Middle East – before they disappeared around 30,000 years ago.

Bonus: Denisova

In 2008, Dr. Pääbo’s team sequenced the DNA from an “exceptionally well-preserved", 40,000-year-old fragment from a finger bone found in the Denisova cave in Siberia. This DNA sequence turned out to be unique – different from all-known sequences from Neanderthals and present-day humans. The previously-unknown hominin Denisova was thus discovered.

Comparisons with DNA sequences of contemporary humans from different parts of the world also suggested gene flow between them and Denisova.

Expert opinion

Dr. Partha Majumdar, National Science Chair of the Science and Engineering Board, Government of India, not only praised Dr. Pääbo’s research but also the technological aspect of it. “His conceptual breakthrough is of paramount importance in understanding human evolution, but at the same time, his technological breakthrough deserves equal praise. It is not easy to amplify and sequence ancient DNA because it is highly fragmented and full of contamination from microbes like fungi and bacteria,” Dr. Majumdar said to The Hindu.

The scientist also said that the Nobel laureate’s research has helped in furthering the recognition of evolutionary biology and paleogenomics. “This is a hard field to follow, especially in places like India and Africa because the ancient DNA is not preserved well in tropical weather conditions.”

It remains to be seen if the renewed interest in the field will lead to better funding and subsequently more opportunities for researchers, Dr. Majumdar added.