Archaeologists investigating Stonehenge’s ancient prehistoric landscape have discovered a series of previously unknown mystery monuments.

By using a special detection method to analyse the ground, they have, for the first time, revealed how prehistoric people were hacking vast circular holes in the Stonehenge landscape’s chalk bedrock.

Around 100 of these mysterious newly discovered rock-cut basins and pits were between 4m and 6m in diameter and in some cases, at least 2m deep.

Some of the holes would have required the systematic removal of at least 25 cubic metres (around 60 tonnes) of solid chalk – a time-consuming task for prehistoric people, equipped only with stone and wooden tools, deer antler pickaxes – and possibly fire (to help fracture the chalk).

Indeed, a small number of rock-cut pits and basins may have involved the quarrying and removal of between 40 and 60 cubic metres (100-150 tonnes) of chalk.

The vast newly found rock-cut prehistoric monuments, scattered across Stonehenge’s sacred landscape, are baffling archaeologists – because, so far, they haven’t been able to firmly deduce why they were created.

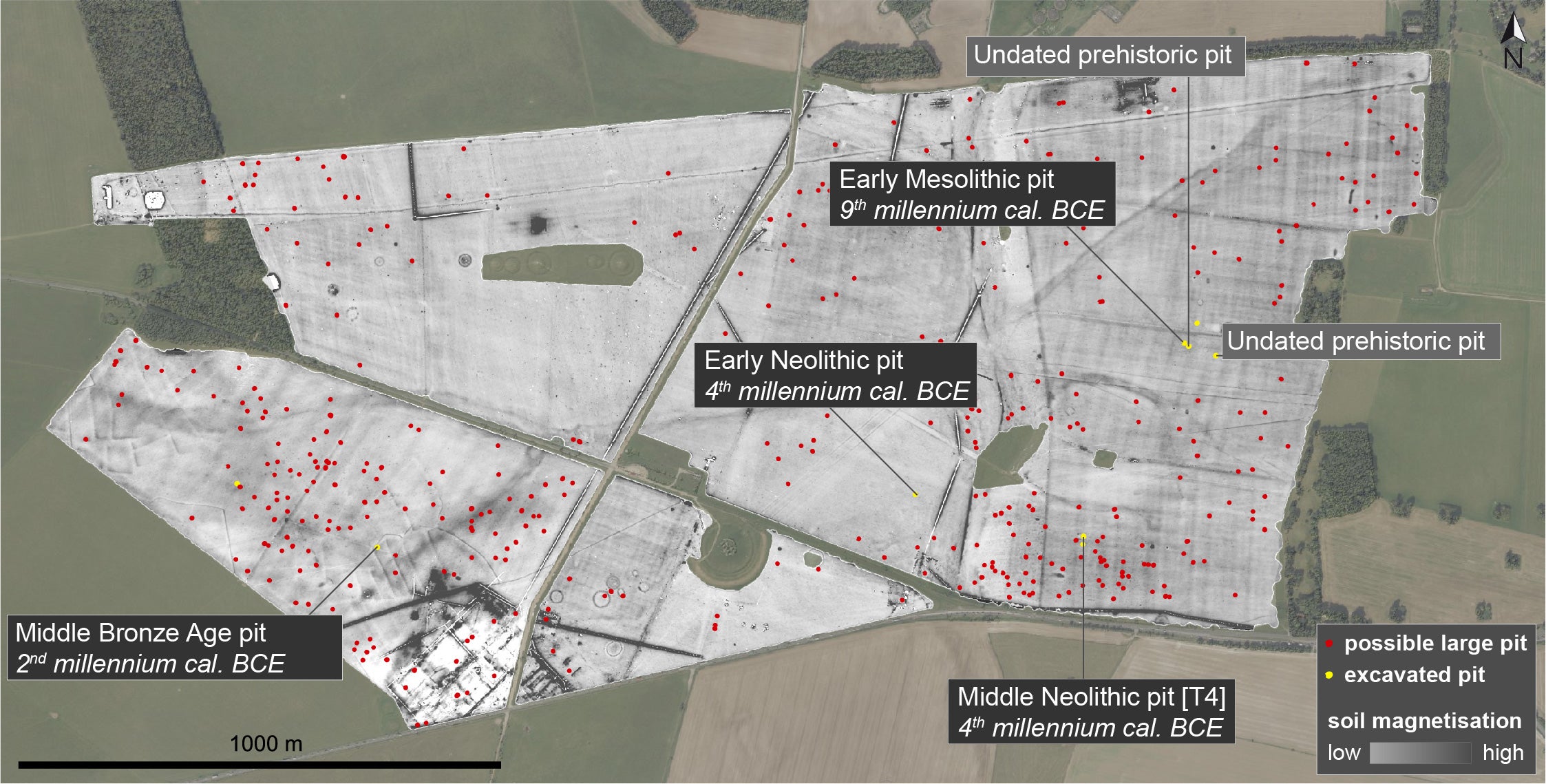

The available evidence suggests that they are a previously largely unknown class of prehistoric monuments, but made at widely differing times in prehistory.

The archaeological investigation has so far demonstrated that the oldest example was made in around 8,000 BC (at least 5,000 years before Stonehenge existed), while others were hacked out of the bedrock 500 years before Stonehenge – with yet others being created while Stonehenge was in decline.

The wide time range for this newly discovered type of large rock-cut monument suggests that in each epoch, their Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age creators, made them for widely differing purposes.

In the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) period, some may have been created as sophisticatedly designed hunting traps.

But in the Neolithic and Bronze Age, it’s likely that many were dug for ritual purposes. Indeed, the major clusters of these newly identified rock-cut pits seem to have been deliberately located so that they overlooked Stonehenge itself, much of which is believed to have been built during the Bronze Age.

“The new discoveries we’ve made demonstrate that Stonehenge’s prehistoric landscape was even more complex than we had thought. Our work suggests that Britain’s most famous archaeological area still has a lot more mysteries to reveal,” said University of Birmingham archaeologist, Professor Paul Garwood, one of the project’s investigators.

The specific detection system the archaeological team has used to analyse the ground is known as electromagnetic induction (EMI) – and it’s the first time that that system has been used on such a large scale. It is also the first time that the system’s efficacy has been ground-truthed through sample excavations.

Using the EMI system, the archaeologists and other scientists – from the University of Birmingham and Ghent University in Belgium – surveyed a full square mile of Stonehenge’s prehistoric landscape.

“Geophysical survey allows us to visualise what’s buried below the surface of entire landscapes,” said Ghent University geophysics expert Professor Philippe De Smedt.

In total, they found up to 2,500 rock-cut pits – including around 300 with diameters of more than 2.5m (around 100 of which had diameters of 4-6m).

The oldest example was a 4m-diameter, 2.2m-deep pit dating from the early Mesolithic period (around 8,000 BC). It had a very unusual y-shaped profile and may have been an animal trap..

The upper part of the “y” consisted of an inverted (though truncated) cone-shaped rock-cut pit, while its bottom half (the tail of the “y”) comprised a vertical 1.5m-diameter cylinder-shaped shaft.

Perhaps significantly, it was located just 10m away from another 1m-diameter circular rock-cut feature (some of which would originally have been up to 75cm deep) and may have been a level platform (deliberately cut into the slope of the hill) for a timber windbreak or rudimentary shelter. This possible temporary dwelling (perhaps some form of wigwam or tent) has not been dated – but may also be Mesolithic and, if so, might well have been used by the hunters who built the probable trap.

Mesolithic structures are extremely rare in Britain. Indeed, if the shallow rock-cut platform (which has several small possible stake holes immediately adjacent to it) is the floor of some sort of Mesolithic dwelling, it would be the oldest “house” site in the Stonehenge landscape.

Although structures from the Mesolithic era are very rare, there is evidence that hunter-gatherers from that period did build a probable ritual monument in the area around what would, millennia later, become Stonehenge. That discovery (evidence for a series of three massive totem-pole-style timber obelisks) was made in the mid-20th century – and the newly discovered Mesolithic rock-cut pit (and potentially the “house” platform) is further evidence of the importance of the Stonehenge area in that very early period.

Data from the Stonehenge landscape investigation has just been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, accessible here, starting today.