Lucy* used to be known fondly as the “iron lady” by colleagues at work. In her mid-50s and still the main breadwinner for her family, she had always thought of herself as strong, energetic, and indestructible – but not any more.

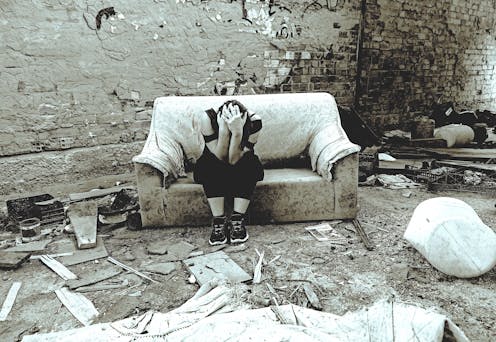

Since contracting COVID in March 2020, Lucy told us she had been struggling with relentless fatigue, joint pain, breathlessness, brain fog and sensory dysfunction. But worse than any single symptom is how this leaves her feeling about her own identity. She said she found herself unrecognisable, a shadow of the person she used to be:

This isn’t who I am – I don’t recognise myself. I panic if I get on the Tube and there’s no seat. It’s a very strange feeling, like not being in your own body. My fear is I’ll never really get better, and that I’m always going to be at 70% of my former self.

In November 2020, Lucy was diagnosed with long COVID, a condition encompassing many symptoms that last far beyond the acute stage of COVID infection – at least 12 weeks but often far longer. In our interviews, Lucy described struggling not only with great physical suffering but an overwhelming sense of losing control over her life:

I was crying and crying – it was absolutely heartbreaking. I just could not get over the fact I wasn’t getting better … I’m not usually a crier but the tears, my God – the physical illness made me feel so tearful, as well as the desperate nature of feeling so ill for so long.

In his 1946 book, Man’s Search for Meaning, the psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl wrote: “Life is never made unbearable by circumstances, only by lack of meaning and purpose.” These words ring true in the story of Lucy, whose illness has brought her face to face with existential crisis as she confronts the realisation that her once rich and meaningful life may have slipped away, leaving her uncertain and fearful about what lies ahead.

I half feel myself shutting down … almost like: ‘Oh, my God, I’m counting the years till I can stop.’ You know, when can I retire? It’s like I can’t picture myself any more in the same way [that I used to], on an upward trajectory.

Are existential crises common?

Lucy’s story is by no means an isolated case. Over an 18-month period from October 2021, we conducted three rounds of interviews with 80 people from diverse age groups, geographical locations and socioeconomic backgrounds throughout the UK. All had self-identified as having persistent COVID symptoms through nationally and regionally representative cohort studies that track the lives and health of people over time.

Strikingly, while sharing their experiences of living with these symptoms, more than half described a profound and, to them, often inexplicable anguish. This emerged as they were forced to question their purpose, even their very existence, in the face of long COVID.

According to past research, doctors and nurses in different areas of healthcare often describe supporting their patients’ existential needs – the psychological dimension of illness spanning feelings of isolation, alienation, emptiness and being abandoned – as one of their greatest care challenges.

Yet there still appears to be only a limited understanding of the way that people experience full-on existential crisis – including among those family members and friends closest to them. This implies a lack of knowledge of the best ways to identify and support people enduring such harrowing periods in their life.

To make matters harder, diseases such as myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and long COVID are viewed with scepticism in some quarters. A reluctance to acknowledge these crippling health issues can potentially hinder both diagnosis and support for sufferers – and exacerbate their sense of isolation.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

While our interviewees may not have explicitly labelled their experiences as “existential”, the question of the nature of who they are lies at the heart of many of their narratives. Emily, who was only 31, expressed her fear of disconnection from both her past and future as she confronted the unknown struggles ahead:

It became very lonely to be in that position and to not understand when, or if, you’re ever going to get better. I try not to think that way, but I do worry that this will never go … Planning for the future, it’s a big thought thinking: ‘Can I do it with this kind of pain – can I or can I not?’

What seems remarkable is that the existential concerns shared with us transcended age, ethnicity, health and wealth, affecting individuals from all walks of life. In this, our study echoes previous research into people with chronic, acute and terminal illnesses, as well as of older people grappling with “feeling forgotten” and fading away, and of teenagers and middle-age individuals during major life-stage transitions.

Existential crises can also centre around experiences such as a romantic break-up or bereavement, or even the global threats posed by climate change. At the core of all these experiences are a profound sense of losing something important and the heavy load of not knowing what will happen.

Losing your identity

For most of our interviewees, living with long COVID caused significant disruption to their daily routines. The aftermath of their infection typically resulted in a wide range of symptoms affecting their breathing, heart and cognitive function. These symptoms often overlapped, changed over time, and made it challenging to return to activities that were once core to their sense of self.

Hazeem, a British Pakistani in his mid-30s, expressed frustration about being too fatigued to fulfil his role as a father during a crucial stage of his young son’s growth:

I feel bad for my little son because he’s five and he’s just started school this year, and sometimes I can’t take him to his swimming now if I don’t feel up to it, or take him to his football classes or gymnastics … I feel like as a father figure, it’s my duty but sometimes my wife has to do it now.

Hazeem appeared deeply concerned about the seemingly never ending threat to his role within the family in the future, adding: “Family has always been important to me … I would say my worries about long COVID are mostly connected to that.”

Older people we spoke to talked candidly about the pain of facing up to a premature end to their active and healthy selves. Andrew, 63, described feeling a “loss of belief in myself and the definition of me as a healthy person … Suddenly you’ve just got something dictating to you what you can and can’t do.”

Younger interviewees wrestled with the unexpected disruption to their formerly vibrant social and educational lives. For Fiona, an athlete in her early 30s, the experience of feeling less competitive had been particularly tough:

A big part of my life has been playing sport at a very high level, but I am not able to be the player I was beforehand … Now, I’m one of the mediocre players and am not given the same responsibilities because I’m just not capable any more. I found it a little bit hard to adjust to – like I’d lost my identity slightly.

Mourning the loss of physical capabilities

In A Grief Observed, C.S. Lewis (using the pseudonym N.W. Clerk) offered reflections on bereavement after the death of his wife in 1960. Drawing parallels between his loss and the amputation of a limb, Lewis suggested both experiences could result in a profound loss of identity in which “all sorts of pleasures and activities that I once took for granted will have to be simply written off”. In this way, Lewis said, his “whole way of life will be changed”.

Our interviewees highlighted similar feelings that we describe as “non-death related grief”. Their emotions were often raw and intense as they confronted not only loss of their former identity and lifestyle, but control of their body. Among those who mourned this profoundly was Susan, 63, who told us:

I always was a fairly confident person, always had big responsible jobs which I sort of thrived on – the stress and all the rest of it. Now, I just feel like I’m a little old lady. I don’t have any confidence at all. I would much prefer not to go out of the house at all, I’ll stay at home and cuddle up … I’m just a shadow of who I used to be.

Sociologist Arthur Frank argued that our bodies provide an important way for us to make sense of our experiences and connect with others. This may help explain how loss of control of the body can give rise to a form of grieving. Interviewees such as Craig, 51, described their regret at having to bid farewell to previously taken-for-granted capabilities, and the sense of self these gave him:

The things I used to really enjoy, like cycling and running, I just can’t do those at the same level now at all … I keep thinking: ‘Oh yeah, I might be all right now, get out and do it.’ But within a couple of hundred metres, I realise I just haven’t got that ability … My whole lifestyle has changed and my whole social scene has changed because of it, as a knock-on effect.

The painful aspect of grief arises from the ruptures it creates in our lives. Meghan, in her early 20s, said that contracting long COVID had forced her to “relearn” how to live life on a daily basis, and that it has been “quite difficult to come to terms with my body – basically becoming this new thing that I don’t really know how to take care of”.

Fear of an uncertain future

Our participants faced daily struggles not only with the grief of losing their cherished past but fear of their uncertain future. As philosopher Søren Kierkegaard puts it: “Life can only be understood backward, but it must be lived forwards.”

People living with long COVID often struggle with both the complexities of ever-changing symptoms and the lack of sufficient treatment options, leading to a constant state of uncertainty – like walking in the dark without knowing where they are heading. Paul, 75, said he had no choice but to “live day-by-day” in the shadow cast by his unstable health conditions:

The biggest worry I have is if anything happened to my wife … if I was left on my own and couldn’t support myself, cook or dress myself … But we’re living for today and trying not to dwell [on that].

Life can be likened to the crafting of a book, with each scene gaining significance only when seen within the context of its broader narrative. Finding coherence in our life stories is crucial to maintaining meaning and purpose, and building a buffer against the challenges of day-to-day life. But for many, long COVID has disrupted this narrative, leading to a profound realisation of their vulnerability and mortality. As Iris, 75, put it:

It knocks the stuffing out of you. You don’t feel the same. I know I’m getting older, but it has made me feel vulnerable and susceptible to illnesses. I’m aware of being more afraid. Well, we all know we’ve got to die, don’t we?

Notably, similar fears were also articulated by some much younger (and seemingly fitter) interviewees such as Kate, who was 21 when we met her:

The narrative I was fed, and a lot of people my age were fed, at the start of the pandemic was: ‘Oh, you’re young, you’re basically invincible.’ But this experience has made me realise I’m actually not invincible, and I get sick quite a lot now because of long COVID … People are much more vulnerable than we think.

Suffering in silence

Existential crises are hard to explain. Many of our interviewees found it easier to articulate the surface-level challenges they faced, while struggling to convey the nuanced experiences of their deeper suffering. In part, this may be because our society lacks the appropriate vocabulary to capture such profound and wide-ranging pain.

Lisa, in her early 30s, told us her struggles were “really difficult to explain” and, as a result, did not believe that her family and healthcare professionals “fully understood exactly how bad it was”. She felt there was “no point really talking about it as I could tell it’s upsetting for people to hear”.

While a lack of understanding may in part be due to limited information about this newly-emerged health condition, the invisibility of sufferers’ pain also plays a significant role. John, 63, said he found it challenging to communicate his “hidden disability” and associated suffering because he was “not in a wheelchair” and didn’t have “a plaster cast on my hand”.

Many of our participants admitted lacking the knowledge to understand and verbalise their painful experiences, let alone their more existential worries. Pat, 51, was among those who found it hard to express their feelings adequately. It was only when her interviewer described similar struggles observed in other participants that Pat suddenly recognised how the concept of existential crisis mirrored her own experiences. She said: “You [the interviewer] have hit the nail on the head. People don’t understand it, but I am very conscious of it.”

The barriers to describing existential crisis can be entrenched by feelings of guilt at how other people may view you – in particular, concern that they think you’re making too much fuss. Lucy, who we introduced at the start of this article, spoke powerfully about how this made her stop talking about her struggles:

You don’t want to be a misery guts. My family had two years of me really very ill, so I try and not share too much – [same with] friends and colleagues. Usually, you might go to a friend and say: ‘I feel depressed and miserable’, and talk it through. But with this illness, you can’t because you feel that you’ve used up all your misery points. It’s like nobody wants to hear about it all the time, so you end up just internalising it and actually that’s quite depressing.

A lack of empathy in society at large can create additional obstacles to recognising and addressing hard-to-explain feelings of loss, regret and anxiety. For 37-year-old Ahmad, a Pakistani immigrant, his struggles of meaninglessness were compounded by his difficulty securing a visa extension to work in the UK – leading to him losing both emotional and material grounds for his existence.:

I became a victim of anxiety. My company did not want to accept that I am ill. I had already taken a six-week sicknote and couldn’t take any more, because my financial position was very weak. I got no help from the government [and] I did not have family that could support me to keep myself alive… Mentally I am affected a lot, I am now mentally ill.

We need to talk about existential concerns

Our study has uncovered a fascinating trend among long COVID patients that we believe carries much wider relevance: profound self-reflection on the meaning of a life, triggered by a major disruption to their existing narrative.

We are all likely to encounter such a point in our lives – akin to feeling detached from both our past and future, causing a loss of meaning and purpose in the present. This sensation can make us feel isolated and desperately seeking validation to justify our existence. Lucy described the debilitating impact of her ongoing battle with long-term COVID symptoms as “like having to learn to walk again”:

It’s really hard, because you no longer get the kind of mental release you get from being physically active … I’ve had to just stop myself and say: ‘No, slow down, take a break.’ Because otherwise I just can’t manage, and that is the most difficult thing of all.

When considering coping strategies, we believe it is essential to promote a better understanding of the prevalence of existential crisis among society as a whole. Not everyone, of course, can access highly specialised support such as existential therapy, which can be a useful tool for confronting existential dilemmas and gaining insight into values and beliefs.

What’s needed is a more accessible way to directly address and discuss our existential worries. For example, psychologist Lauren Breen and colleagues have called for “grief literacy” to help create more compassionate communities. This initiative aims to encourage people who have experienced loss, as well as the wider community, to become more knowledgeable and proactive in supporting those experiencing grief in everyday conversations and interactions.

A European research project has created a programme to help healthcare professionals engage in existential conversations more sensitively and confidently. Such initiatives are particularly important in mental health and peer support settings – encouraging people to engage with both professionals and peers who share similar experiences, facilitating open conversations and fostering a sense of understanding. Sharing life stories is also a way to bring feelings of loss and uncertainty into the fabric of daily life.

In our view, the key to supporting people in times of existential crisis lies in the power of empathy, where grief, fear and anxiety are listened to and validated. Indeed, attaining a deeper understanding of these experiences may help open a door to positive self-reflection, potentially revealing new perspectives and meanings in life.

Ultimately, when reflecting on his experience of living with long COVID, John described finding some comfort in the transcendent nature of his struggles:

Everything, everything by which I defined myself was taken away … I was left with ‘who am I?’ and ‘what is the meaning of life?’ Big questions which felt very profound and gave me a huge insight into suffering, and a compassion for other people who suffer – whether someone’s a refugee or they’ve broken their leg. I suppose I went on a very deep internal journey. Whereas before I’d been used to going on external journeys like walking or climbing, I went on an internal journey that’s equally as adventurous and challenging – and continues to be so.

*All names have been anonymised to protect the interviewees’ identities

For you: more from our Insights series:

Loneliness, loss and regret: what getting old really feels like – new study

GP crisis: how did things go so wrong, and what needs to change?

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Chao Fang received funding from UKRI and NIHR (COV-LT-0009) for the study reported in this article. A special thank you to all the participants who took part in this study. We would also like to express our gratitude to Laura Sheard (Associate Professor, University of York) for providing feedback on a draft of this article.

JD Carpentieri received funding from UKRI and NIHR (COV-LT-0009) for the study reported in this article.

Sarah Baz received funding from UKRI and NIHR (COV-LT-0009) for the study reported in this article.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.