I recently got the chance to visit Fox at its Californian headquarters as part of the press event for the release of its new GRIP damper range. As you would expect, the Scotts Valley HQ has offices and function rooms loaded with fancy water machines and walls adorned with retro Fox suspension and history, however downstairs is where all the interesting stuff happens. Alongside the kitted-out workshop, Fox houses some of its product development testing facilities. A component torture chamber filled with all manner of odd contraptions for testing suspension, wheels, and other components.

Fox’s Test Lab Manager, Kurt Siever, showed me around and explained what some of the machines were up to.

If you think you would be happier not knowing how much your suspension fork might be flexing while riding, maybe skip the below video.

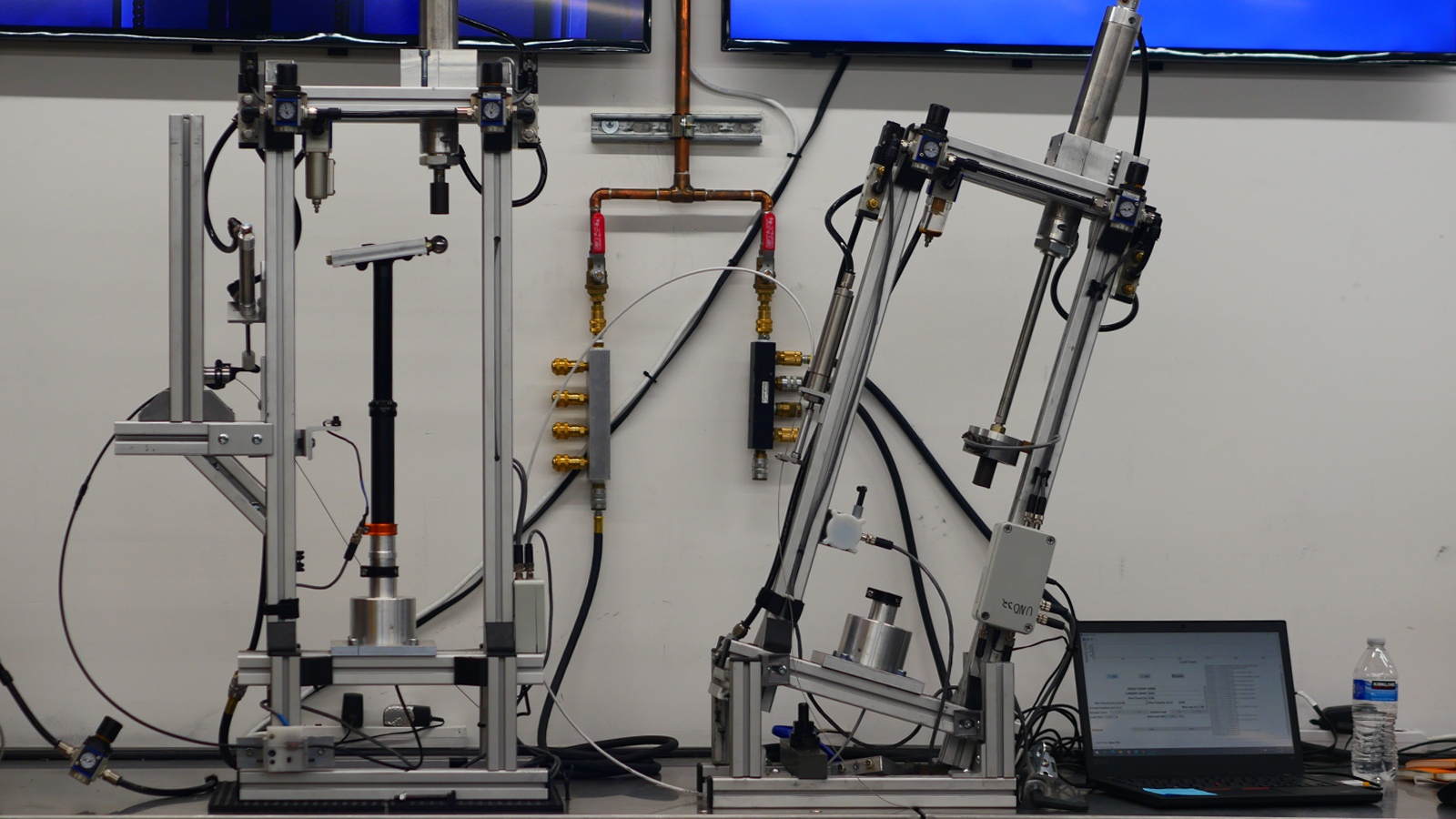

The testing facilities are spread over two rooms, both crammed with many machines bending, twisting, and cycling through specific movements or actions. This isn’t Fox’s only testing facility, regulatory ISO testing which involves large quantities of fatigue testing is generally performed in Taiwan. That frees up more time for development testing at the Scotts Valley and Canadian labs, with the Canadians focusing mostly on wheels and wheel impact testing.

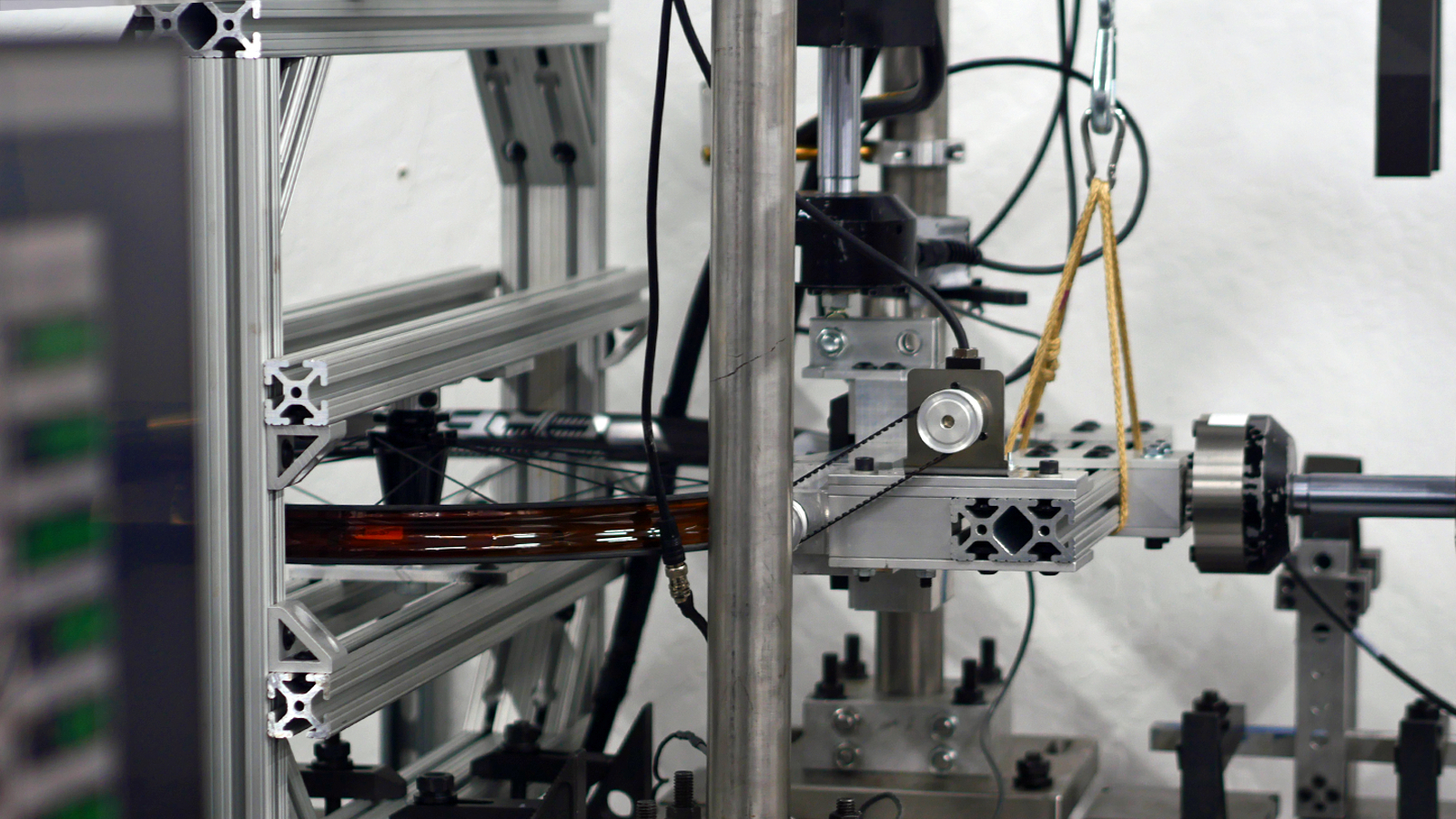

It's a flurry of activity with the suspension testing machines hard at work analyzing all aspects of suspension. Depending on the tests, these machines can run for days carrying out millions of cycles on a product. Not only are all the machines performing different tasks but the bank of computers in the middle of the room is busy harvesting around 1,000 data points per second.

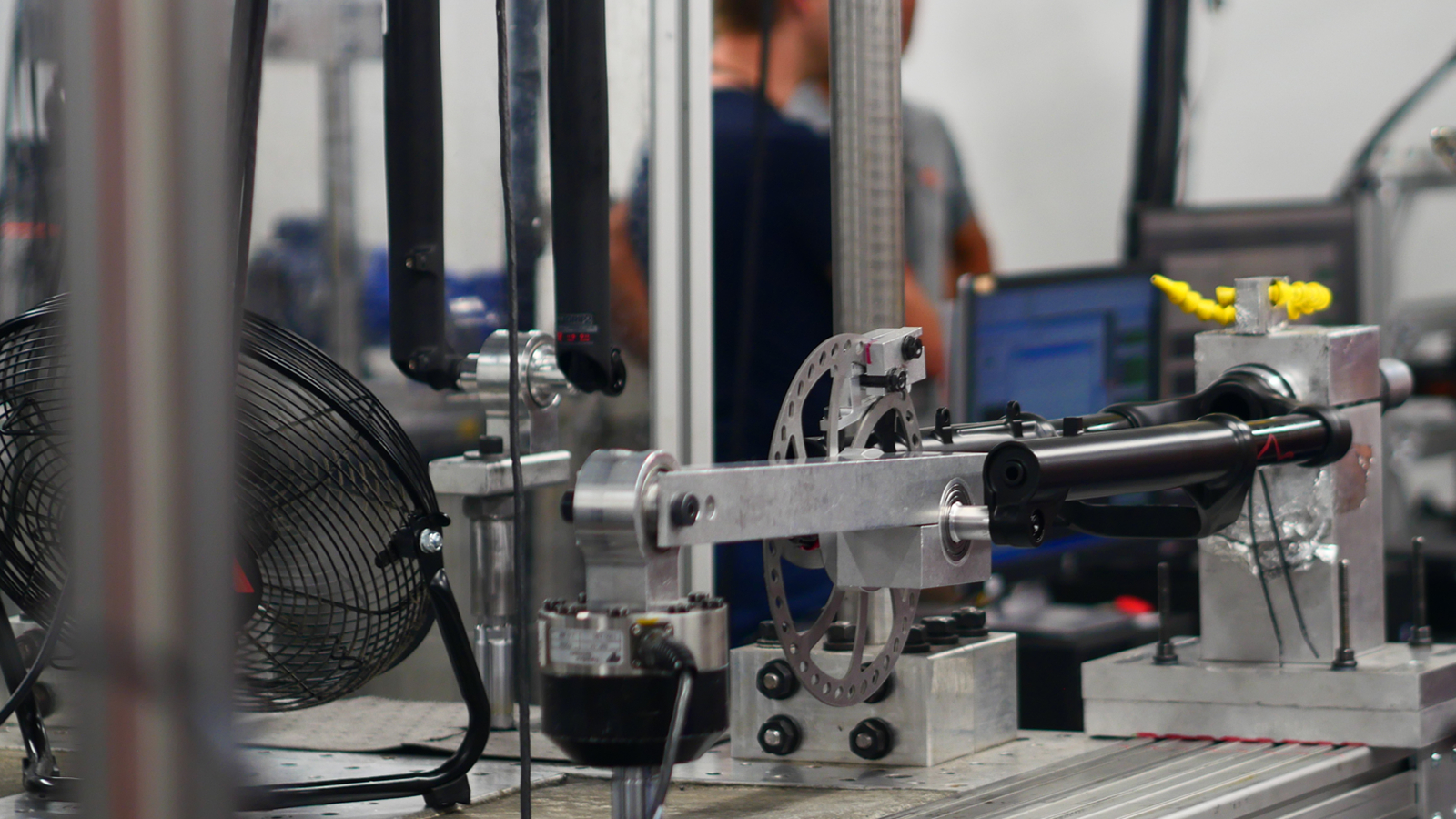

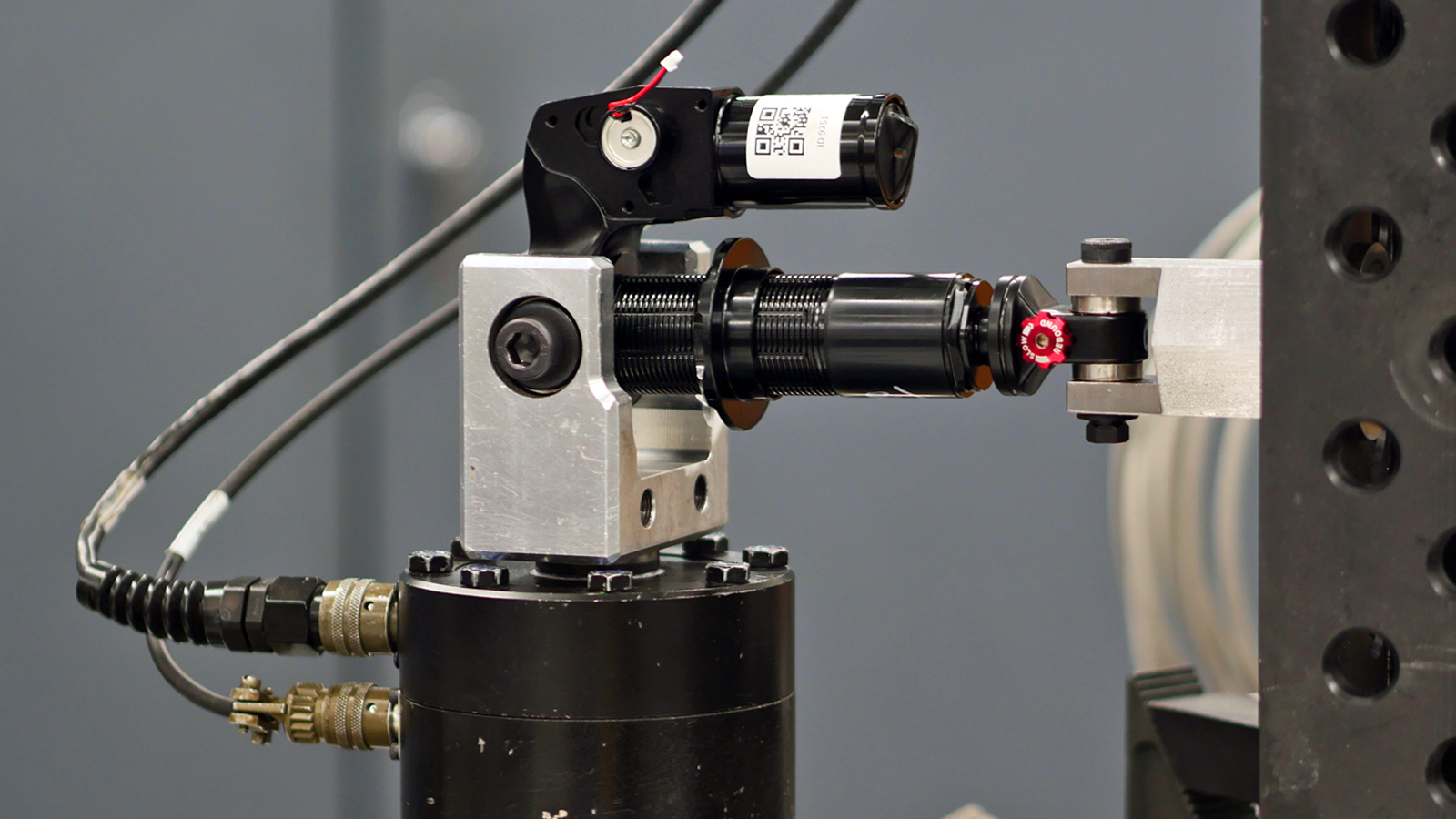

One of the most interesting tests was the Downieville Test. The test team strapped a load of strain gauges and telemetry to a bike and sent one of the engineers down a descent at Downieville. The test rig then uses the resulting data to cycle a suspension fork for 100 hours, repeating the same trail profile to replicate around six months of use. Every now and then the process will stop and the machine will slowly cycle through the fork stroke to analyze the condition of the damper. They had a similar test being performed on a shock too, tracking a six-minute segment using the profile from a local trail. The shock was also side-loaded with a 25lb weight to pull it out of the axis and increase wear during the test.

Although the torsional testing are most interesting to watch, Fox is also benchmarking all manner of other variables. Experiments with different tubes, oils, seals, and bushings are all documented in order to find the best performance. Fox has even tested inverted fork concepts on this machine, they worked decent although didn't perform as well on the torsion tests.

It feels a bit like organized chaos with everything happening around you and it sounds like it can get pretty messy sometimes. Whether it’s spraying forks and shocks with calibrated dirt to test seals or finding oil all over the floor in the morning after something has gone pop in the night.

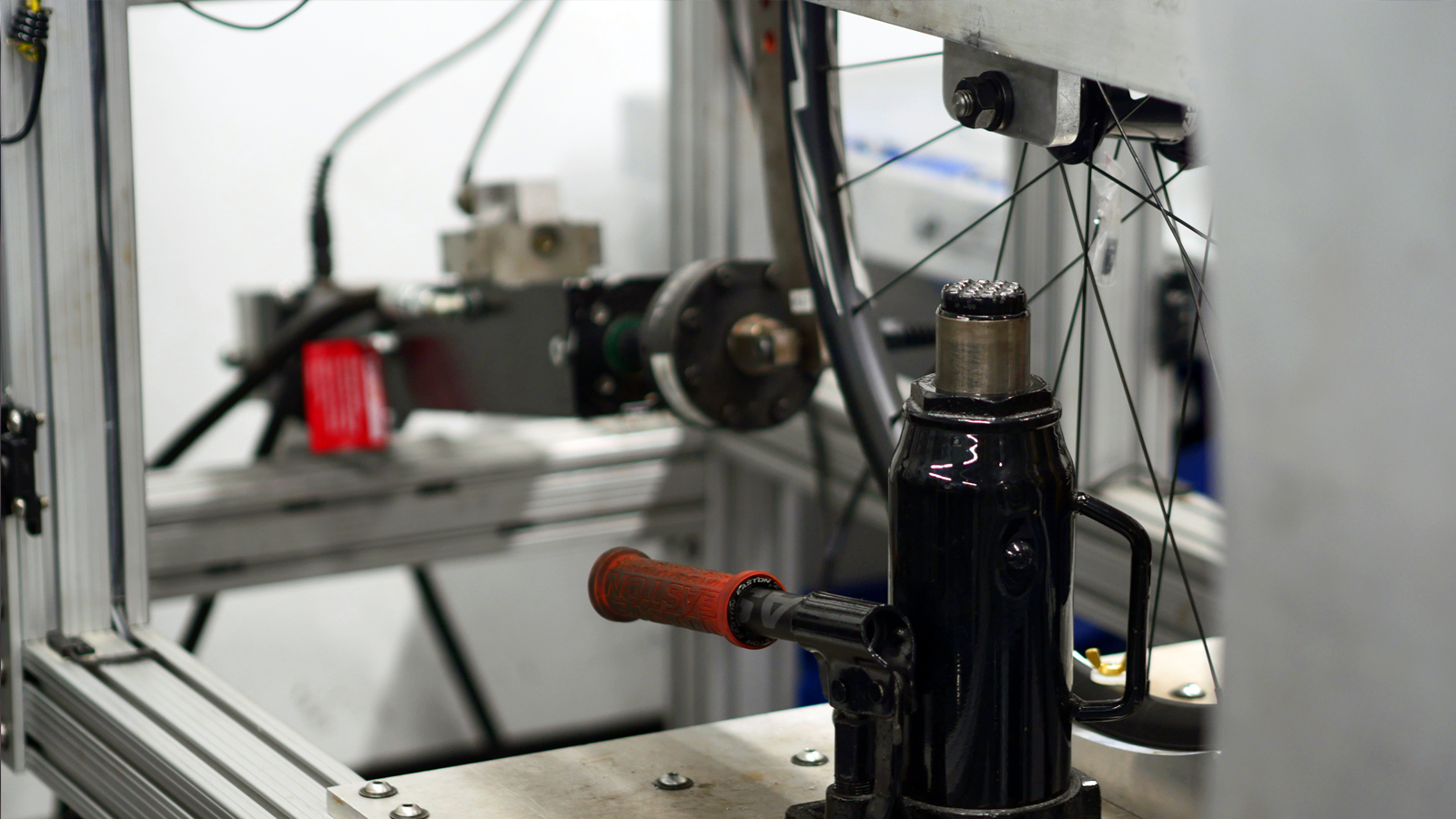

Compliance was a major consideration during the development of Race Face’s Era wheelset and although most of the testing is performed in BC, there was some wheel testing happening here too. This machine clamps the hub and applies lateral force to the wheel to test the compliance of a rim. Wheel ride feel is very subjective but this machine can be used to back up real-world testing with hard data.

The second room houses the heavier machines. Some of these are mounted on cement blocks and perform sensitive tests with each rig isolated to eliminate crosstalk from the other machines. There’s also the excitingly nicknamed “Mega Impactor” which is used to test forks to destruction, ensuring that if a fork does fail on the trail it's not going to separate into many pieces and make a bad crash even worse.

Fox is developing new MTB products, and the machinery used to test them is becoming increasingly advanced too. As all the shiny new machines are hard at work, several older testing tools are sitting at the side. The old wheel impact testers were basic gravity-driven rigs and involved having a technician yank the stick out and get out of the way. These have now been replaced by more accurate, repeatable, although less exciting, computerized impact testers.

There are also a couple of wheel-testing machines. The older rig is a basic spinning drum, and although it's 15 years old, it's still used to perform basic initial benchmark tests. The new machine is far more sophisticated, driven by a chain and rocking back and forth to imitate sprinting and cornering, failures to carbon rims are said to be very similar to the type of failures from actual riding.