Small and medium-scale farmers and agri-businesses in east and southern Africa are getting a raw deal. To succeed they need fair and integrated regional markets. Research by the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development has highlighted the need for better integration of regional economies as a step towards food security in the region.

Powerful commercial interests, high transport costs and poor access to facilities such as for storage mean that small and medium-scale farmers are often not getting fair prices for the food they grow. Fair prices are those that meet demand and cover reasonable costs of supply including transport across borders.

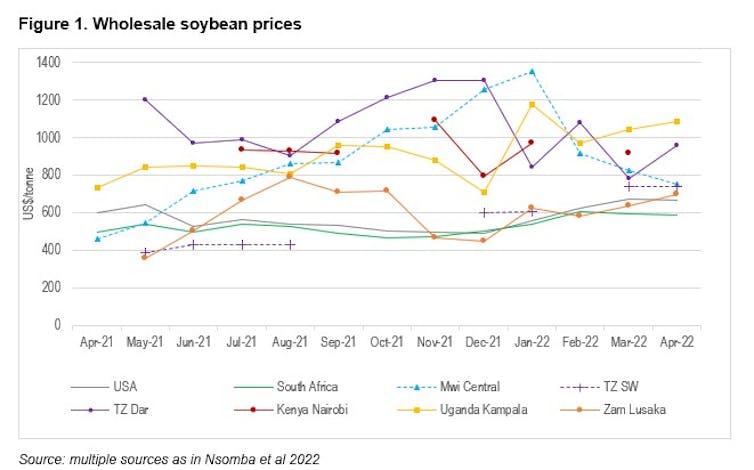

During the course of our research we came across examples of how the odds are stacked against most small and medium-scale farmers. Take the experience of Endrina Maxwell, a small producer in Malawi. In April 2021, she sold her soybean crop in central Malawi and realised the returns from investing in commercial agriculture as a female agribusiness owner and farmer. She got prices around Malawi kwacha 350/kg, about $450/t (see Figure 1). At the same time, the prices in the main markets in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi were over a $1000/t.

A number of hurdles stood in Endrina’s way to take advantage of the high prices in neighbouring countries. First, specific price information was not readily available for someone in Endrina’s position to be aware of the gains from exporting. Second, transport costs are very high for smaller producers. Third, to hold-off from selling at the harvest and to bargain for better offers, producers like Endrina need to have storage options.

This situation does benefit some. These include the main traders and processors in Malawi and across the region. These companies bought up much of the crop at the time of harvest at low prices, for local use and for export, taking advantage of their storage facilities and private information. Prices in Malawi then increased to peak at $1350/t in January 2022, as if there was a severe scarcity.

The trebling of soybean prices affected another cohort of small-scale farmers. Soybeans are a key component of poultry feed. Small-scale poultry farmers saw their animal feed prices increase by similar amounts, squeezing them severely.

Our research identifies a lack of effective regional competition and indicates the need to inquire into transport, storage and logistics issues. The differences in prices between locations on transport corridors translate into rents to transporters and arbitrage margins being made by large traders. It also points to supplies being bought-up by intermediaries at low prices at the harvest and held back to drive prices up.

The fragile food systems in the region, combined with increasing concentration at multiple levels of key value chains, calls for a regional competition policy for resilient and sustainable regional value chains.

A stronger regional market referee to monitor and enforce competition rules would level the playing field for fairer food markets.

The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa Competition Commission working together with national competition authorities, has the central role to play.

What’s missing

The African Market Observatory was created to fill the gap of reliable market information for key food products at the wholesale and producer levels. The observatory tracks and compiles prices monthly. The first 12 months of data gathering by the observatory underlined the benefits to smaller market participants of market data.

This year, with the African Market Observatory, it has been possible to track markets through crowd-sourcing prices from smaller market participants. Access to this data has allowed Endrina to anticipate what she should get for her soybean harvest. It has also enabled her to plan her other business – oil production – more efficiently.

The pricing patterns have highlighted the crucial role that access to competitive transport services as well as storage facilities play in accessing markets and fairer prices. This has informed Endrina’s decision to invest in storage facilities on her farm as a result of discovering that there is value in spreading her grain sales throughout the year as opposed to selling only at the harvest.

To strengthen the region’s fragile food security – made worse by climate change –it’s essential that produce can be sourced from across the region, which is the most cost effective way to meet the needs of customers and to reward producers for expanding supply.

This is most evident in Kenya where food prices have risen exponentially. The country is experiencing the most severe drought in 40 years. In addition, the war in Ukraine is compounding international pricing pressures.

This means that Kenya needs to source imports from the region where weather has been good at fair competitive prices. Yet, despite growing production in countries such as Malawi and Zambia, cross-border trade is not happening effectively.

Unfair trade

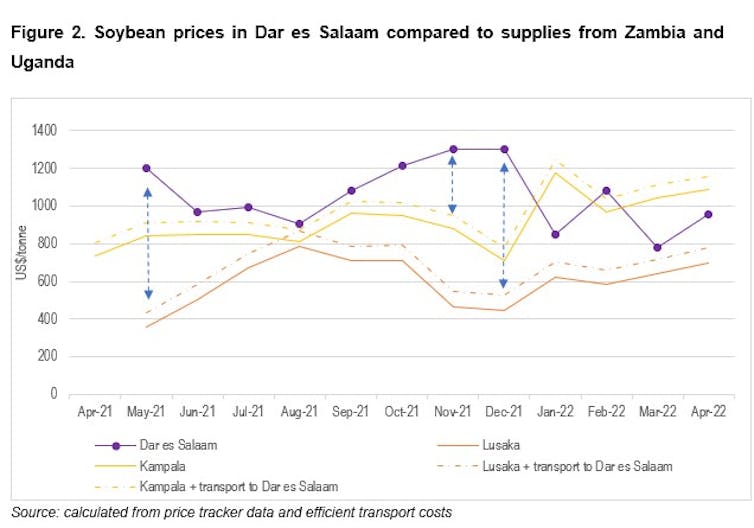

By considering the market clearing sources of supply for the main centres of demand in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi we can see that soybean prices have been way above the fair import prices. This implies that producers received too little and end users paid way too much, with intermediaries capturing the difference.

Dar es Salaam could have sourced soybeans from Malawi, Zambia or Uganda – all neighbouring countries – to add to domestic supplies. Prices at over US$1200/t in some months, such as October to December 2021, were US$200-400/t above what it should have cost to land goods from Uganda and US$400-750/t above what it should have cost to land from Zambia. This includes an efficient transport rate, calculated at US$0.04/t/km from various sources.

Regional trade and competitive markets are also impeded by governments. Zambia had an export restriction on soybeans from August to November 2021. Removing the restriction brought lower prices to buyers in Dar and higher prices to sellers in Zambia, benefiting both sides through trade.

Where the region is unable to take advantage of good supply in some locations to meet demand in others at competitive prices, this places great pressure on downstream industries. For example, animal feed producers in Kenya who are buyers have been hit hard.

A package of interventions to ensure regional markets work better is urgently required.

Making regional markets work

We propose the strengthening of three priority areas:

policy and advocacy,

enforcement, including against cartels; and

regional merger evaluation.

Competition advocacy and policy is essential, as many of the factors undermining effective regional competitive markets include policy aspects. Regulatory barriers, for example, undermine trade and reinforce the market power of companies within countries.

The Comesa Competition Commission and national authorities in the region need to urgently act together in these areas to tackle poorly working regional food markets.

The African Market Observatory is a starting point for data collection where analyses can be deepened, collaboration can be strengthened, and access to pricing information improved for market participants.

The Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development at the University of Johannesburg in which Simon Roberts is lead researcher has received funding for the African Market Observatory from the COMESA Competition Commission.

Grace Nsomba does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.