Faded American, Mexican, Texas, and German flags ripple in the wind and a single wind chime softly clinks at a makeshift memorial at the Walmart in El Paso where a white supremacist killed 22 people and injured two dozen more on August 3. Prayer candles, bouquets, photographs, and handwritten messages stretch for hundreds of feet behind the fenced-in store, which will forever be known as the site of one of the country’s worst mass shootings and most heinous acts of racist domestic terrorism.

Today, the 6-foot-high covered fence makes it difficult to see the parking lot and front of the store. But catch a glimpse, and you’ll spot the cars of construction workers, who have raced to strip the store’s inside down to its studs and complete a dramatic remodel that will include a permanent memorial for the victims.

The store is tentatively scheduled to reopen in just two weeks, on November 6. “Nothing will erase the pain of August 3 and we are hopeful that reopening the store will be another testament to the strength and resiliency that has characterized the El Paso community in the wake of this tragedy,” a Walmart spokesperson told the New York Times in late August.

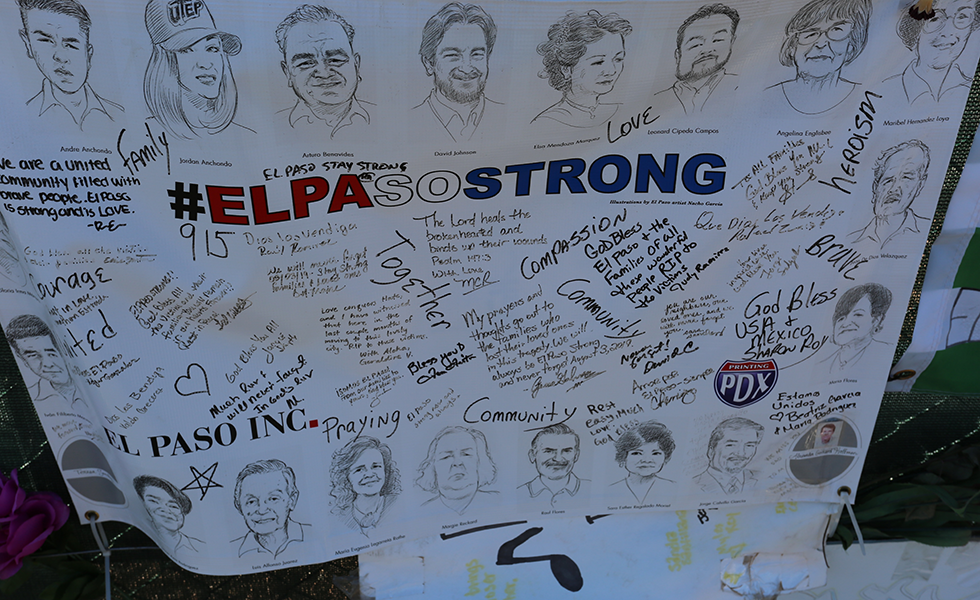

Many see the store’s reopening as part of a necessary return of quotidien routines in the city, marking the community’s resolve not to let the shooter disrupt their way of life. Indeed, when traversing the predominantly Hispanic border town, it’s hard to avoid the phrase “El Paso Strong.” Plastered on fast-food restaurant marquees, graffitied wall murals, tattoos, T-shirts, and bumper stickers, it’s come to define the community’s defiant response to the racial violence that attacked the city’s binational identity and its embrace of immigrants and refugees. (The gunman published a manifesto online before the massacre, detailing his intent to murder Latinos “in response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas.”)

Resiliency was also a consistent theme evoked by city leaders at a hearing this week of the Texas Senate Select Committee on Mass Violence Prevention and Community Safety, a task force formed, in part, to learn about the impact of mass shootings on victims, families, and Texas communities. “I’m going to make darn sure that this event does not define El Paso,” Dee Margo, the city’s mayor, said Monday afternoon at the University of Texas at El Paso campus, where more than 100 local officials, victims’ families, advocates, and residents gathered to testify. “It will be relegated to an asterisk footnote as part of the El Paso history.”

The border community’s response to the shooting was astounding. Thousands offered blood, food, services, time, money, and other support. But many at the hearing warned against misconstruing “El Paso Strong” as a sign of full recovery, or using it as a cover for political equivocation and inaction. As dozens of testimonies made clear, El Pasoans are still struggling to grapple with the tragedy and the shooter’s motives, as well as the resulting ripples of trauma, grief, fear, and anger.

“You cannot help, after August 3rd, but look over your shoulder,” El Paso County District Attorney Jaime Esparza told the senators. The community’s strength and unity should not be taken as a sign that everyone has healed, he warned. “What is forgotten … is the nuance of the secondary trauma that will affect this community. We give ourselves a sort of ‘It won’t define us, so muscle up,’ and ‘We are strong, so muscle up.’ That is a good solution, and I think it’s one way to move toward healing. But there are lots in this community for who muscling up is not the answer.”

Educators, social workers, mental-health advocates, and immigrant service providers all testified about the heavy burden that the shooting has had on the psyche of El Paso residents. Whether direct or indirect, no one has gone unscathed.

“El Paso will never heal from this shooting,” said Arlinda Valencia, president of the Ysleta Teachers Association, which represents teachers in El Paso County’s largest school district. Her great-grandfather was murdered along with 14 other men and boys in the Porvenir Massacre—one episode in a long history of racial violence along the U.S.-Mexico border. “That happened over 100 years ago and my heart aches for my great-grandfather and the other victims every single day. El Paso will move forward, but the hurt and the memories will never die,” she said. “We also must work to take care of those who survived and ensure their health, because they will suffer.”

Wearing a brown checkered suit, Michael Grady, a pastor and former president of the El Paso NAACP, sat before the committee and testified on behalf of his 33-year-old daughter Michelle Grady, who survived being shot three times by the gunman. “This carnage has affected our family and our city. It’s taken away the concept of safety,” Grady said. “The fear is in the atmosphere. You can’t shoot it. You can’t legislate against it.”

*

El Paso, along with the rest of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, has increasingly found itself at the center of a dark moment in American history. The region is used as a political prop to stoke racial resentment and anti-immigrant fearmongering; the Walmart shooting was a potent and devastating manifestation of that moment. The haven of safety and solidarity that fronterizos knew El Paso to be—despite the president’s best efforts to convince the country otherwise—had been punctured.

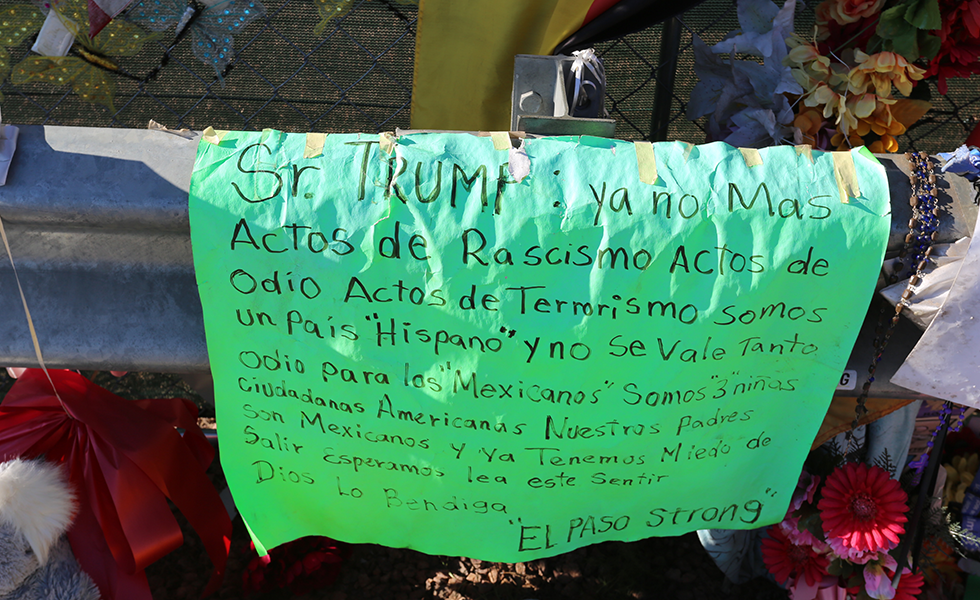

For the many El Pasoans who are Latinx, immigrants, and the children of immigrants, the shooter’s determination to inflict his deep-seated hatred upon their community has created immense personal and existential anxieties. People at the hearing spoke about how El Pasoans remain on edge, wary of going shopping or taking their kids to school. They talked about people always knowing where the exits are, of friends having panic attacks, and of themselves being inherently suspicious of outsiders.

The Senate Select committee was formed in the wake of the mass shooting in Midland-Odessa, just one month after the El Paso shooting. It’s charged, in part, with addressing this very issue: What impact do these shootings have on communities? The committee is also intended to study the causes of mass violence, extremism, and white supremacy, as well as figure out how to keep guns out of the hands of potentially dangerous individuals—all without infringing on the Second Amendment.

The impaneling of committees and holding of roundtable discussions has become a familiar, even rote, part of how Texas leaders like Governor Greg Abbott respond to mass shootings. After the tragedy in El Paso, but before the one in Midland-Odessa, Abbott formed a Domestic Terrorism Task Force with the aim to “root out the extremist ideologies that fuel hatred and violence in our state” and improve coordination between law enforcement agencies.

(Attorney General Ken Paxton, a member of the task force, has either missed or ignored at least one glaring warning sign about a potential threat of racist violence. As the Texas Observer first reported last April, a white man in San Antonio has sent several troubling messages about his Latinx neighbors to the Attorney General’s complaint portal that was set up to take tips after the enactment of the anti-sanctuary city law SB 4. “WE WILL OPEN FIRE ON THESE THUGS WHO WILL NOT LEAVE US ALONE… WE HAVE CALLED IN OUR OWN HELP AND IT WILL BE A BLOODBATH,” one message read. Paxton’s office never referred the messages to San Antonio police, according to a city official.)

Despite the distinct sort of evil associated with the El Paso shooting, Monday’s hearing—which lasted for more than five hours—sometimes felt pro forma. People rushed to get through their prepared testimony within the allotted time, while the committee members listened with varying degrees of interest. Many advocates invoked familiar solutions, calling on the committee members to enact red-flag laws, expand background checks, and limit the sales of assault-style weapons and extended magazines. Meanwhile, gun-rights activists warned lawmakers that such ideas would impose upon their right to bear arms. This is the dynamic that plays out in the wake of every mass shooting.

But activists continued to emphasize that El Paso was not like every other mass shooting. “We’re sitting in this room because a hate crime was committed,” Jody Casey, a Moms Demand Action activist and former campaign manager for Beto O’Rourke’s 2018 Senate bid, reminded the senators.

Bigotry and racism are playing a growing role in American mass shootings, and Texas law is woefully ill-equipped to keep guns out of the hands of dangerous people. According to a report by the Giffords Law Center, under state law, those who are “convicted of violent hate crime assaults and hate crimes involving ‘terroristic threats’ of violence are generally able to legally buy and keep guns, including assault weapons, immediately after conviction.”

Extremist activity is on the rise around the state. The number of hate groups in Texas has grown from 30 in 2014 to 55 in 2018, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. As the San Antonio Express-News reported, a “Deport them All” banner was unfurled in a mostly Latinx neighborhood in Fort Worth last year. Flyers reading “Keep America American” were passed out in Round Rock in June.

For Andrea Reyes, an El Paso native and political director of the activist group Deeds Not Words, the shooting was the product of a uniquely pernicious combination of unregulated gun culture and state leaders’ “white supremacy and racist rhetoric.” She recalled the time that former state Representative Matt Rinaldi threatened to shoot Poncho Nevárez, a Hispanic legislator, in the head during a heated encounter over anti-sanctuary city legislation on the Texas House floor.

Governor Greg Abbott recently found himself in hot water when it was discovered that, on the day before the El Paso shooting, he had sent out a political fundraising letter that invoked alarmist anti-immigrant rhetoric. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick also has a long record of immigrant-bashing. That is all, of course, to say nothing of the president.

Republicans’ hateful rhetoric, Reyes said, is the “same as the bullets that armed the semi-automatic weapon that entered my community and killed 22 people.”

El Paso state Senator Jose Rodriguez, a member of the Senate Select committee, agrees that right-wing rhetoric about immigration both in Texas and nationally has emboldened racist extremists like the El Paso shooter. “I’ve made no bones about it. I’ve called that out. This has got to stop,” Rodriguez said in an interview in late September. “It’s just not going to be the same anymore after someone in this country puts a target on Latinos’ backs. That’s just not going to be tolerated in the future.”

He is adamant that the committee, along with state leaders and legislators, take seriously its charge to study and consider the drivers of “radicalization of individuals and incitement of racism, white supremacy and domestic terrorism” and not just go through the motions.

Locals also question the efficacy of these kinds of committee meetings. Seth Van Matre decided on a whim to testify. He grew up in El Paso’s Cielo Vista neighborhood and says that it hit him hard when he learned that the shooter had specifically targeted his fellow Latinos.

“I don’t talk about [these feelings] a lot,” he told me after testifying. “I thought that coming here would be an almost cathartic moment.” But for some reason, the sense of despair that has been with him since the shooting did not lift.

He never thought that something like this would happen within a mile of where he had grown up, where his family—and everyone else in his community—shopped. “Honestly, I’m not sure things are going to change. I really thought that we lived in a different place,” Van Matre said.

He paused. “I don’t know. I think I was more optimistic before August the 3rd.”

Read more from the Observer:

-

Author William Lopez on How Immigration Raids Inflict Long-Lasting Trauma: “There are 364 other days in the year when people’s lives are shaped by the possibility of deportation or a raid.”

-

An Observer Staff Guide to the 2019 Texas Book Festival: It’s an embarrassment of riches.

-

Bonnen’s Downfall Proves Politicians Don’t Mind Dirty Laundry—So Long as It’s Never Aired: The Texas House Speaker announced his resignation, becoming another example of the trite adage: it’s the cover-up, not the crime.