Editor’s note: A year ago, shoppers at a Walmart in El Paso found themselves in the crosshairs of white supremacist Patrick Wood Crusius, a 21-year-old from Allen, a town outside of Dallas, during one of the country’s worst mass shootings and most heinous acts of racist domestic terrorism. In this evocative essay, a veteran journalist talks about what’s happened to her beloved El Paso and its stout residents since the shooting. This essay also appears on the websites of palabra by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists and El Paso Matters.

Eduardo Castro, known as Eddie, couldn’t wait to get out of the car. He was impatient with the time it was taking to retrieve his walker from the trunk. On a hot summer day, he had crossed the border from Ciudad Juárez in Mexico so he could see the woman he calls his angel.

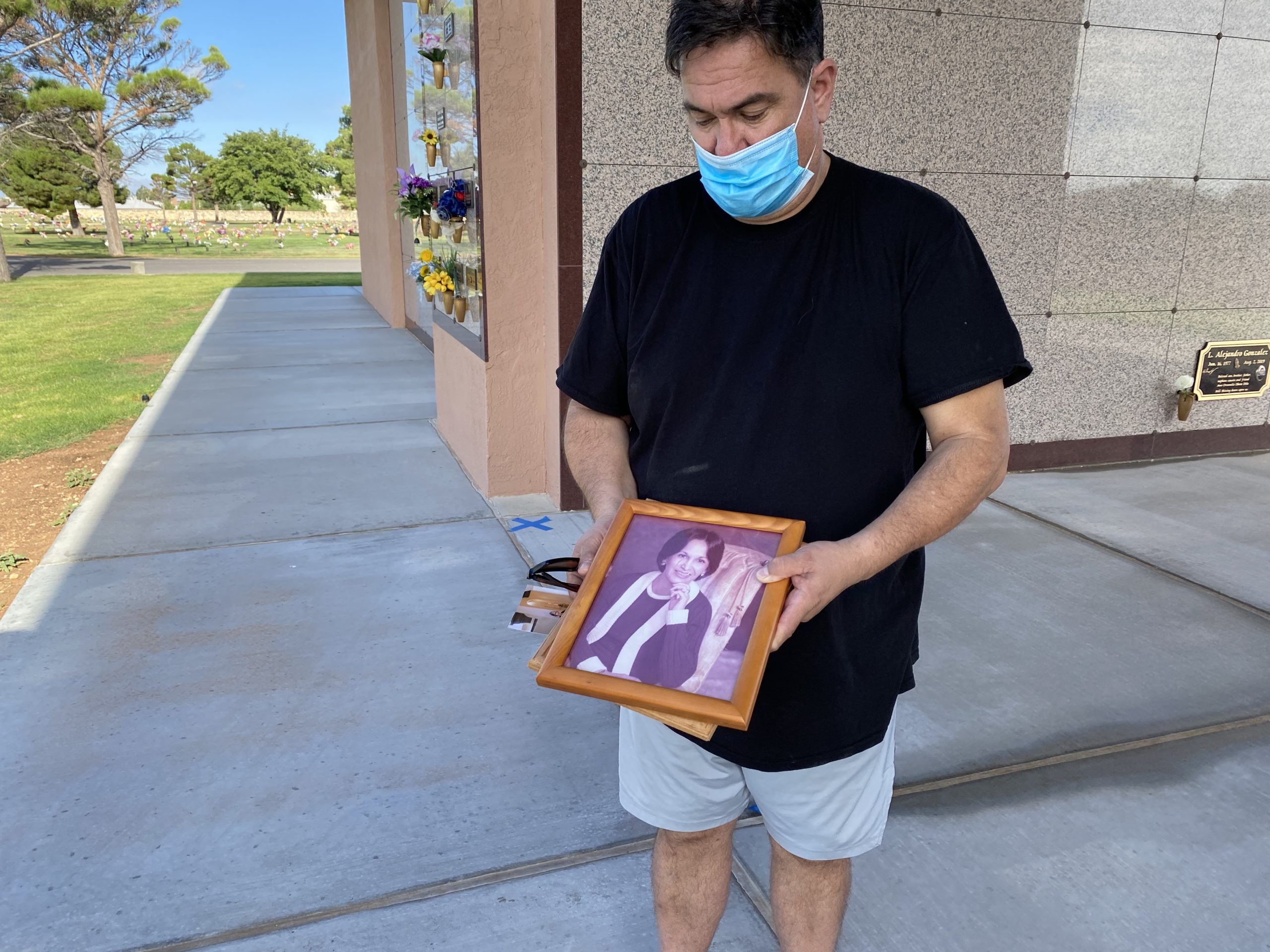

It was their first connection since the mass shooting—the deaths of 23 people and the wounding of dozens more—at the Walmart store on El Paso’s east side. Castro, 72, was full of emotion as he greeted Adria Gonzalez and her mother. Talk quickly turned to that day, August 3, 2019, and the deep wound that still stretches across the long border between Texas and Mexico. For the next two hours, the trio recounted what had happened; how life changed the moment they heard the snaps of rapid gunfire.

It had quickly become apparent to them that something bad was coming their way.

“There goes another one, boom, boom, boom,” Castro said, gesturing as if he was holding a large rifle, firing off rounds.

Adria Gonzalez, joined in, adding her own recreation of the sounds of the shooting. “Boom, and then boom, and boom.”

At first the gunshots sounded distant, they agreed. But then the sounds grew closer.

Soon the awful toll was clear: 20 people lay dead. Dozens more were wounded. Shock and chaos ruled the rest of the day.

Two more victims would die days later. Another died in April, nine months after the mass shooting.

Hate’s long drive

In the midst of the horror that day, there were also moments of heroism. Gonzalez saved his life, says Castro.

Their conversation flowed easily in Spanish, Castro’s preferred language. To mark today’s COVID-19 reality, they wore masks and stood several feet apart, even when they found shade from the blistering summer heat under a small group of trees.

There were moments of silence and sobbing. And for me, as I observed the reunion, saddened but also inspired, there was a deepening recollection of what was really on display one year ago.

I remember getting the first alert with the words “mass shooting” on my phone, and staring at the words in disbelief. It’s a Walmart we all know well.

The shooter targeted El Paso because of what it is—a predominantly Latinx community on the western edge of Texas, embracing Mexico as much as it does the United States.

After listening to Castro and Gonzalez, I fully understood that who we are and where we live on the border is how we are able to cope with the trauma of an attack that tested this resilient city.

The gunman told police he had come to El Paso to “kill Mexicans.” He drove from North Texas, traveled more than 650 miles and 10 hours “to stop the Hispanic invasion of Texas.” He outlined this in a diatribe posted on an online message board promoting white supremacy.

Binational bonds

The gunman came to kill “others” he viewed as foreign invaders. Those inside the store during his deadly rampage saw each other as family.

That unbreakable bond unites friends and families on both sides of the border.

Gonzalez, 38, is a U.S. citizen with deep roots in Mexico’s Chihuahua state, where her mother, Agueda Ponce Torres, 75, hails from. She looked at Castro as akin to her own “abuelo”—grandfather. Castro, a former construction worker in several U.S. cities, refers to Gonzalez as “mija”—my daughter.

“People don’t understand, in El Paso, we’re a family, from Juárez to Chihuahua to Parral,” Gonzalez explained, naming major cities in the Mexican state.

“We’re siblings,” added Castro, apologizing for having to sit down. He relies on a walker because he regularly feels unsteady. Since the attack, he’s become unwilling to talk to others about what happened inside the Walmart store—even avoiding the subject with his son and wife. He also has trouble eating and sleeping.

A good day for shopping

On that Saturday morning a year ago, the lines on the bridges from Juárez to El Paso were as long as they usually get on weekends before the start of the school year. Mexican shoppers here cross legally every day to spend hard-earned pesos-turned-to-dollars on consumer goods and groceries.

Castro was one of those shoppers. Like many in this binational community, he’s a legal U.S. resident who spends a lot of time in Ciudad Juárez with his family.

That day, Gonzalez and her mother Agueda, were debating meat prices inside the Walmart. Castro had just cashed his Social Security check at the bank inside the store and was in the produce section, collecting items for his wife.

That’s when they met. That’s when Gonzalez rushed to the front of the store to usher shoppers back as the gunman approached.

“When I heard you yell. I followed you and took off running,” Castro recalled. Many could not escape, including a 90-year-old man.

More than half of the 23 people killed were 60 or older, including 86-year-old Angelina Maria Silva de Englisbee.

On the anniversary of the shooting, her son William Englisbee is focused on her memory and on the family’s proud legacy.

“Her dad in World War II fought in the Philippines,” William Englisbee said. “She had three brothers, all in the military. My grandfather, her father Marcelino Silva, was born in Lamy, New Mexico, before New Mexico became a state in 1912. Goes way, way back hundreds of years in Santa Fe with my mom’s side of the family.”

A haunting like no other

Along this stretch of the border, where three U.S. states and two countries intersect, many people are immigrants and have roots somewhere else. We choose to live here. That makes it easy to straddle the border. I grew up in Guadalajara and Texas. For many years, I was based in my native Mexico City, in a news bureau as a well-traveled foreign correspondent. I’ve covered violence and bloodshed, from massacres and cartel killings to migrants brutalized by organized crime.

Yet, it’s the Walmart hate crime that haunts me like no other. It was a mass murder in the most mundane of settings. It’s easy for any of us to imagine loved ones in the store, picking up kids’ backpacks at that moment.

Since the shooting, many motorists driving through El Paso have taken the exit off the I-10 freeway that leads straight to the Walmart parking lot and made a spontaneous pilgrimage to visit the makeshift memorial outside the store. The memorial has now been replaced by a candela that glows at night. Many Latinx parents plan road trips to the spot as a powerful teaching moment for their children.

Our geography and our particular West Texas history are also why many Latinx families in the United States feel a connection to the Paso del Norte region, especially those whose immigrant story began in what’s called “Ellis Island of the Southwest.” Someone’s abuelito, tío or tía, crossed through this region long ago, or maybe just yesterday.

Those are the strong stories that connect us across time and distance.

For me, and many, many others who live here and draw strength from El Paso, it is still the only place I truly feel at home. Somehow I find that I fit in here, just like Eduardo Castro and Adria Gonzalez and William Englisbee. A racist’s bullets won’t change that.

Read more from the Observer:

-

From Boom to Bloodbath: The Permian Basin’s shale revolution is over and renewable energy is surging. What does that mean for Texas’ future?

-

How COVID-19 Threatens Texas’ Restaurant Industry: The COVID-19 pandemic threatens the future of the barbecue joints, taco trucks, bánh mì shops, and country cafes that make up Texas cuisine.

-

Inside the Dallas Morning News Union Fight: North Texas journalists want to make labor history in the Lone Star State. The A. H. Belo Corporation would prefer they didn’t.