He is the visionary behind the Eden Project and the Lost Gardens of Heligan, two innovative, pathfinding Cornish attractions that draw hundreds of thousands of visitors a year.

But Sir Tim Smit’s bid to create a third landmark project in the far south-west of England – an education centre for horticulture, agronomy and cookery on a Cornish hillside – has suffered a setback after residents of the ancient town of Lostwithiel protested in their droves and, for the moment at least, managed to halt the scheme in its tracks.

Smit, who caused huge upset earlier this year for suggesting the Cornish are not articulate and too fond of looking back to imaginary “good old days”, had claimed the Gillyflower Farm scheme would be an important research centre for crops of the future and boost the economy of Lostwithiel, a medieval capital of Cornwall.

However, hundreds of residents objected, claiming its prominent position would spoil precious views from the town and from the ramparts of the spectacular Restormel Castle, and were singularly unimpressed that – in their minds – Smit had not consulted with them properly before pressing ahead.

At a fiery meeting of Cornwall council’s strategic planning committee in Truro on Thursday, members voted by seven to four to reject the recommendation of their own officers that the plan should be approved, several saying they were disappointed at the consultation process of Smit’s team.

Sarah Chudleigh, one of the residents who spoke at the meeting, said afterwards she was “overwhelmed” at the councillors’ decision. “I think it’s wonderful for the town,” she said.

Chudleigh said she feared that if it were allowed, the development would suck business away from the town centre, and the jobs it would create for local people would tend to be less skilled and poorly paid. “So much of Cornwall is being developed but it’s not for the sake of the people, it’s for the financial gain of the rich and powerful,” she said.

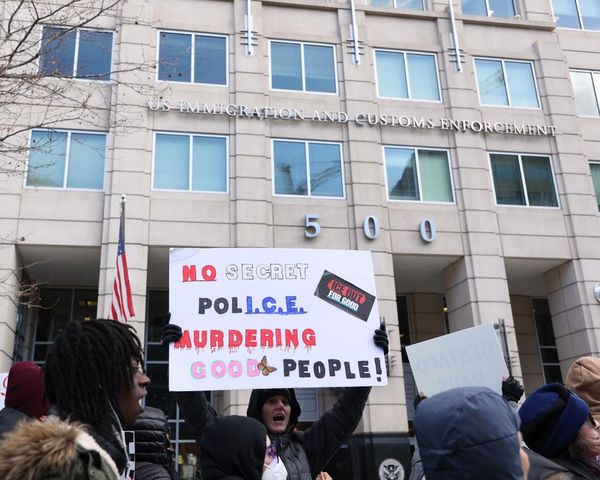

Lively demo outside New County Hall in Truro ahead of a decision on a new Sir Tim Smit project pic.twitter.com/vHGH6qSxqr

— steven morris (@stevenmorris20) April 14, 2022

On the project’s website Gillyflower is billed as “a third chapter from some of the team that brought you the Eden Project and the Lost Gardens of Heligan”.

Smit and his family, who live in the area, have already restored a “sustainable” golf course there and planted orchards and gardens filled with rare, historic fruit trees.

As well as the education centre, they were hoping to create 19 holiday lodges, a cafe, a shop selling goods produced at the site, a distillery and microbrewery.

But the opposition was clear before the Truro meeting with a song written for the occasion performed as councillors arrived: “Stand, Cornwall, stand! / Every day they’re taking your land / And greed is bulldozing your traditions away / Oh stand for yourself, Cornwall stand!” Placards featured slogans such as “Community not greed” and, even more bluntly, “Orchard my arse”.

During the meeting Smit said the climate emergency meant projects like Gillyflower, which is named after a traditional Cornish apple, were needed.

“The demand for horticulture is going to go through the roof,” he said. “What most people don’t seem to understand yet is that in the attempt to get away from the current agricultural models we are going to have to find a whole range of crops that are not totally dependent on fossil fuels.

“The whole point behind Gillyflower is a training facility for the development of heritage fruit and vegetables. We’re creating wealth, creating partnerships and making Lostwithiel resilient for a future that still remains ours to make.”

Smit’s team told the meeting their own polling had shown that 70% of local businesses supported the scheme, though conceded that the project may have had a “less bumpy ride” if more consultation had been done earlier.

Colin Martin, the Lib Dem councillor for Lostwithiel, insisted the project would harm a place designated an area of great landscape value. He said if the town became more of a draw, more people would buy second homes, as they have done in the Cornish harbour town of Padstow since the arrival of Smit’s friend, the celebrity chef Rick Stein, making it harder for local young people to find a place to live.

Outside the meeting, Martin said Smit’s criticism of the Cornish had not helped his cause. “He has sometimes spoken about Cornish people, giving the impression he is better than all of us and we should be grateful for the good things he has bestowed upon us.”

He anticipated that Smit would appeal but hoped, meanwhile, that bridges could be built. “It’s a really tight-knit community,” he said. “I have been shocked and saddened by how this application has caused a wedge in the community. People have been driven apart. I hope we can put this behind us and rebuild community spirit.”