Martha Karua, the running mate of Raila Odinga, the losing candidate in Kenya’s 2022 presidential election, continues to dispute William Ruto’s slim victory over him. According to the politician and lawyer, the Kenyan electoral commission and the country’s supreme court

failed Kenya’s democracy and infringed on the human rights of Kenyans when they ratified President William Ruto’s win.

This is why she intends to bring the matter before the East African Court of Justice.

As the judicial organ of the East African Community, the court was set up in 2001 to ensure the adherence to law in the interpretation and application of and compliance with the treaty that binds the regional bloc of seven countries. These are Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda.

For everybody concerned with the progress of regional integration, challenging Kenyan presidential elections in the regional court is good news. It is not necessarily about what the court will say about the quality of the elections, but about the decision’s long-term implications.

Every decision sheds light on the regional bloc’s basic values. Case law shows countries how to live up to those values. And a high-profile case creates awareness of the court’s mandate and mission.

The regional court needs and deserves public attention. Unlike most of the regional institutions in Africa, it hasn’t been captured by political elites. It is a court of the people with a broad jurisdiction.

Initially, the regional court limited itself to declarations of treaty violations. With time, it moved to order more robust remedies, such as compensation for aggrieved parties. It also started instructing governments to take certain actions to remedy violations.

I have studied the development of the East African Court of Justice over the last few years. My view is that the court has been a keen promoter of the rule of law, democracy and human rights. It has also challenged the elitist legacy of regional integration in East Africa and shaken up the top-down decision-making processes in the East African Community. The court did so by engaging with civil society and national judiciaries, thus bringing the regional bloc closer to the people.

A court of the people

The East African Court of Justice is a very accessible court. Any person who is a resident of the bloc can file a petition – the treaty calls it individual reference (Article 30). Anybody can challenge treaty violations in the court directly without first engaging their national authorities or courts. There is no need to demonstrate any personal interest in the outcome of the case – it can be filed in the public interest.

The court has encouraged individuals to use it through a generous approach to the litigation costs. There are no filing fees and even a losing applicant does not have to pay any instruction fees to the state’s attorney general.

Moreover, the court has gone to great lengths to be physically closer to the people. Even though it is seated in Arusha, in northern Tanzania, there is no need to travel there to file a case. The court operates an electronic filing system and is establishing sub-registries in all capitals of the bloc. It’s also holding hearings in national judiciaries’ court stations across the region.

The court did not decide a single case in the first couple of years of its existence. As the cases finally started coming in the mid-2000s, the court experienced a backlash which limited its accessibility. In 2007, Kenyan politician Anyang’ Nyong’o and 10 other applicants brought a petition about flawed processes of election to the East African Legislative Assembly. The court agreed with the applicants.

It was apparently inconceivable to the national governments that the court they had created would dare to oppose them. Politicians rushed to put the court in its place. They introduced the time frame for individual references, making it harder to approach the court.

What cases are most common?

Cross-border trade disputes make up only a few of the court’s cases. In one case, a private company won US$20,000 as compensation for Burundi custom authorities unlawfully seizing a truck carrying perishable goods.

Awarding of damages is, however, a new practice. The majority of cases concern violation of the bloc’s values, most notably the commitments to the rule of law and human rights. A groundbreaking judgement was handed down in 2007 in the James Katabazi case. A group of treason co-accused in Uganda had been rearrested after being granted bail by their country’s court. The regional court denounced the rearrest as a violation of the rule of law.

Other cases followed. For example, the East African Court of Justice has ruled against secretive detention without trial of a Rwandan army officer accused of committing crimes against national security. And it ruled in favour of the Media Council of Tanzania against legislation which granted a government minister sweeping powers to

prohibit or otherwise sanction a publication of any content that jeopardises national security or public safety.

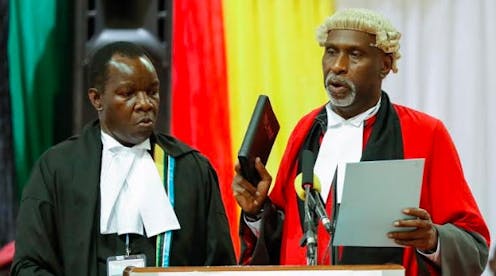

But what is interesting in the context of the upcoming petition from Kenya is an earlier judgement – in 2020 – in favour of Martha Karua. After unsuccessfully contesting a gubernatorial seat in Kirinyaga, she filed an electoral petition with Kenyan courts. It was dismissed on procedural technicalities and she was never heard on the merits. According to the East African Court of Justice ruling, Kenya violated the right to access justice, and hence the principle of the rule of law.

Only as strong as its partners

The court holds great potential for justice in the region, but it is only as strong as its partner states allow it to be. The partner states are under treaty obligation (Article 38) to implement the court’s judgements without “undue delay”. If a state fails to do so, the applicant can go back to the court, since the failure to implement a judgement is in itself a rule of law violation, a violation of the treaty and contempt of court.

The enforcement of a judgement depends ultimately on the given state’s commitment to the rule of law. And as stated by the former Kenyan chief justice, David Maraga, it is herein that the greatness of any nation lies.

Tomasz Milej does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.