While it may have taken decades for world governments to wake up to the very real existential threat posed by climate change to the future of our planet, we have dreamed of the horrifying prospect of the natural world rising up against us for even longer.

Most tribal societies believed in an earth goddess, like the Ancient Greek deity Gaia, standing guard, and perhaps we still fear her pursuit of justified vengeance against us for the hurt we have unthinkingly inflicted on an environment we depend upon.

In Virgil’s Aeneid, the entrance to the underworld is referred to as “Avernus”, a name derived from the Greek for “birdless land” and a detail that speaks volumes.

Victorian novels published amid the bustle and belching chimneys of the industrial revolution like Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights (1847) or Great Expectations (1861) by Charles Dickens cast the Yorkshire moors and Kent marshes respectively as brooding, living characters, cruelly indifferent to the follies of man but ever-watchful.

In Thomas Hardy’s Return of the Native (1878), Egdon Heath is even more fully realised as a godlike presence, its brambles reaching out like idle claws to tear at the clothing of his characters as they pass by, as though actively seeking to restrain them.

In 1885, the Wiltshire nature writer Richard Jefferies published After London, one of the first post-apocalyptic science fiction novels, in which he imagines the fall of British civilisation and the countryside moving in to reclaim the land.

Forests grow where ploughed fields once lay, domesticated pets run wild and the capital reverts to a poisonous swampland, its citizenry returned to a state of feudal barbarism.

Better recognised genre writers like Jules Verne and HG Wells gave early expression to unspoken disquiet about the consequences of unrestrained technological “progress” in fantastic adventure fables of their own.

Wells’s The Island of Doctor Moreau (1897) is a cautionary warning against playing god and tampering with the natural order, just as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) had been to the Romantics and Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park (1990) would be to the late 20th century.

Decades later, after two brutal world wars that had seen the gilded-age certainties of imperialism overturned and the nuclear strikes on Hiroshima and Nagasaki realising Avernus on earth, science fiction thrived like never before.

How could it not? Man’s capacity for orchestrating his own annihilation had been amply demonstrated and the Cold War doctrine of mutually-assured destruction was now a reality of everyday life.

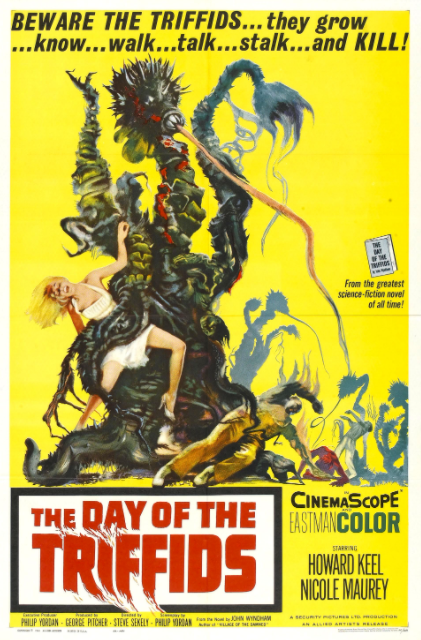

Post-war dismay led many authors to look beyond the stars at the possibility of alternative lifeforms on less tarnished planets, with John Wyndam’s The Day of the Triffids (1951) imagining Britain ravaged by carnivorous extraterrestrial plant creatures following a meteor shower, the evil flora breaking out of Kew Gardens to wrestle back control as though man had proved himself no longer worthy of the responsibility of administering earth.

“All plants move. But they don’t usually pull themselves out of the ground and chase you!” frets scientist Tom Goodwin in the 1962 film version.

The organic alien spores gestating inside doomed astronaut Victor Caroon in Nigel Kneale’s seminal BBC series The Quatermass Experiment (1953) threaten world domination until the plucky British Army destroys his mutant form in Westminster Abbey, another nightmare of ecological counter-attack.

Across the Atlantic, America’s appetite for atomic age B-movies was developing and already imagining the possible repercussions of nuclear waste and radiation.

“What the cumulative effects of all these atomic explosions and tests will be, only time will tell,” observes physicist Thomas Nesbitt after setting off a nuclear bomb in the Arctic in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), the answer being the release of a ferocious prehistoric dinosaur from the ice, prone to devouring lighthouses and stomping through central business districts in search of prey.

Based on a Ray Bradbury story published in The Saturday Evening Post, the film would inspire Ishiro Honda’s Godzilla (1954), perhaps the ultimate embodiment of the natural world revolting and raging against frail human tyranny, although Moby-Dick, the Creature From the Black Lagoon, Jaws and other leviathans might contest the title.

Godzilla is, of course, still with us, recently seen beating up King Kong in Adam Wingard’s latest city-smashing punchathon.

Nature also fought back in Daphne du Maurier’s 1952 short story ”The Birds”, famously filmed by Alfred Hitchcock 11 years later, in which seagulls begin dive-bombing the residents of a Cornish coastal village like kamikaze pilots, their motives eerily uncertain but prodding at our collective sense of guilt nonetheless.

Another interesting mob of mutants rear up in schlock producer Roger Corman’s Attack of the Giant Leeches (1959), in which the annelids in question have been caused to mutate to grotesque size by radiation leaking into the Florida Everglades from Cape Canaveral, a plotline perhaps intended as an implied critique of the costly US space programme.

Corman, incidentally, would also explore the phenomenon of homicidal Venus fly traps in his 1960 black comedy Little Shop of Horrors (borrowing from Arthur C Clarke’s story ”The Reluctant Orchid”), as would British horror studio Amicus in the “Creeping Vine” segment of its 1965 film Dr Terror’s House of Horrors.

JG Ballard’s entirely prophetic second novel The Drowned World appeared in 1962, set in the tropical London of 2145, in which the polar ice caps have melted and society has been forced to adapt, one more pertinent reminder of man’s ultimate helplessness against the elements.

That same year also brought the publication of Brian Aldiss’s Hothouse, about our world growing warmer since becoming trapped in locked rotation with the sun, both Aldiss and Ballard writing about climate change just as Charles Keeling’s observations about the “greenhouse effect” of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere were being roundly ignored.

Ballard’s own vision of drought bringing about man’s downfall, The Burning World, appeared in 1964. The “cli-fi” genre was now well established.

Its ecological themes were soon picked up by Ursula K Le Guin, whose 1972 novel The Word for World is Forest concerns humanity colonising a new planet, whose inhabitants live in perfect harmony with their ecosystem, in order to plunder it for logging, inciting violent uprising through their shameless habit of stockpiling.

That work in turn inspired James Cameron’s later eco-blockbuster Avatar (2009), a film Le Guin detested but which is part of a spate of recent mega-budget spectacles imagining our succumbing to the elements.

These include Kevin Reynolds’ notorious flop Waterworld (1995), Roland Emmerich’s geo-storm drama The Day After Tomorrow (2004), Bong Joon-ho’s new ice age dystopia Snowpiercer (2013) and George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) in which the last survivors on a parched earth eek out a wretched junkyard existence while a decadent dictator hoards the last of the water supply.

Climate scientists have typically been left frustrated by these event movies, with the US National Resource Defence Council launching its Re-Write the Future campaign to pressure Hollywood into more overtly connecting the spectacle to the facts and calling for greater accuracy and engagement with the ongoing state of emergency, taking exception to a film like Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014) that argues for simply leaving the galaxy when our existing natural resources are finally spent.

Eco-warrior protagonists have been the stuff of comic book fiction since 1941, when Arthur Curry AKA Aquaman first made his appearance in DC’s More Fun Comics #73. Essentially a superhero version of the mythic King Neptune, he is a defender of the seas who can talk to dolphins and started out blowing up Nazi U-boats before being given a grungier makeover in Jason Mamoa’s Snyderverse incarnation.

In Marvel’s X-Men, Storm, who controls the weather, is likewise an elemental prescence with echoes of Mother Earth.

More sinister environmentalist characters from comic pages include Batman antagonist Poison Ivy, a botanist turned eco-terrorist who first appeared in 1966 and was memorably played by Uma Thurman in 1997’s Batman & Robin, and Swamp Thing, a conflicted anthropomorphic vegetable beast owing something to HP Lovecraft’s octopus god Cthulu.

Swamp Thing’s duty is to protect the Parliament of Trees and, like Ivy, he communes with “The Green”, a conscious force binding nature at the roots.

Arguably the sharpest expression of our contemporary extinction anxiety is Reverend Ernst Toller in Paul Schrader’s First Reformed (2017), a pastor in upstate New York who becomes traumatised by the suicide of an environmental activist in his parish.

“Somebody has to do something!” the Reverend Toller cries, unable to comprehend the damage we are doing to god’s creation and terrified by the apathy he sees all around him.

He is both a frightening expression of a life lived without hope and a frantic wakeup call for action.

Equally urgent but decidedly more homely in its appeal was the well-intentioned early nineties children’s cartoon Captain Planet, which hoped to impress the need for conservation on young minds through the deeds of its heroic title character, a Superman-style deliverer or reverse Toxic Avenger, summoned by the four elements to “take pollution down to zero.”

Only The Lorax (1971) or Michael Jackson’s “Earth Song” have been as earnest.

Perhaps a new icon of Captain Planet’s square-jawed stature is called for to encourage real engagement and imaginative solutions to our collective predicament, rather than more resigned prophecies of extinction like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2005) and James Bradley’s Clade (2015), in a moment when time is assuredly of the essence.

Discussing the entrenched pessimism in our climate fiction and whether it is leading to a wider sense of helplessness, author Ken Liu told the BBC’s Climate Question podcast that writers must turn their attention towards more utopian visions of the future instead of fetishising our “terrible modernity” if we are to escape the birdless land of ancient nightmare.